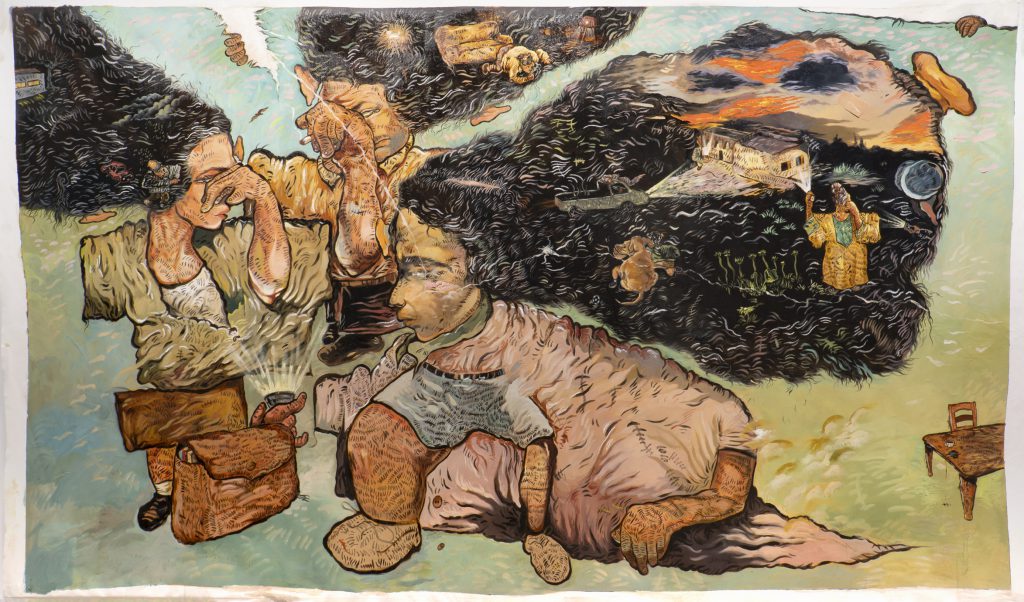

The artist’s works reflect upon often painful childhood memories of the brutal US invasion of Iraq through a home town fictionalised as “the small farm”.

You currently have two shows running concurrently, In The Head’s Sunrise at Brief Histories in New York (ends 28 January) and In The Head’s Dusk at SAW Centre in Ottawa (ends 4 March).

Ali Eyal: It’s the first time in my career that I’ve had two solo exhibitions on at the same time. As a lot of my work evolves from my mind and my memories, I wanted to play with the two titles to discuss my move from Europe to the United States, seeing the sunrise in one city and the dusk and sunsets in other cities. I’m happy to see all my fragments come together. At both locations, I am showing my work The blue ink pocket, and (2022), which I did for documenta fifteen last year; at Brief Histories I decided to make it into an installation with new projects and paintings, while at SAW, I’m showing the video. I often play with my works; I am trying to keep them alive by changing or losing fragments.

You work across various media, including video and performance, but you also create a lot of works on paper. Are particular media able to express certain subjects or emotions better than others?

I’m following my ideas and need to consider what medium might best express a particular idea, which is why I started as a painter. I keep moving from one medium to another and going with different stories. I use art to find new ways of seeing and hearing stories, and I’m always trying to find a new story at the back of my head. All the works are based on a fictional farm that I’ve created and keep returning to, but with different stories and different scenarios. I see the various media as witnessing tools, like inside a courtroom, but all based on my mind and memories.

Your works are surreal, but very personal at the same time. Are the images you create spontaneous?

Most of my work comes from simple ideas and is not based on research. I’m full of memories of events that happened when I was a kid in Iraq and I keep returning to them – I just change the names and events. For example, once my mom bought me a rotten orange just to show me how the colours change on the surface, and once she changed all the furnishing inside the house just to try and forget what had happened to us and refresh. So I don’t have one project; it’s linked as one story, a continuation or an open book.

Do you find creating art helps heal?

Sometimes it can be a healing process, especially giving a piece of fabric emotions and life or creating a video work to bring the thoughts out of my mind and make them alive in different ways. I started from real stories, but things have developed and now I’m writing a memory of a future, witnessing things that didn’t happen, or happened but we didn’t know it was a crime scene or we didn’t know what was behind it. It’s like hiding behind the furnishings that exist in my world, or in the back of my head. War hides itself, so we can’t see it yet somehow it is in everything.

I had already documented the things that happened to me and at some point, I felt that I had finished that chapter in my life. One day I made a video called Tonight’s Programme (2017), which was a way to say goodbye to my father as a missing person. But it’s not only him, as most of my family are missing because of the conflict [in Iraq]. I felt that I had to make this video as if I was meeting them at a coffee shop or place just to say goodbye.

You don’t allow your face to be photographed.

When my uncle was released, I asked him if I could make a portrait of him and he refused. He just showed me his back, which was very powerful to see. I’m also hiding myself away from “shooting” photographs, as this word in Arabic, as in English, means the same as someone using a gun.

Texts often complement your works. Do you see text and poetry as another form of drawing?

It’s very important to see my works like pages with numbers. Every work is indexed like a book. My process starts with a white page as a text and next I try to make that text into an object; the object decides what the medium should be. So it’s all linked.

Text and documentation played a big role in No Part Of This Book May Be Reproduced, In Any Way, By Photocopying, Recording, Or Otherwise, Except With The Prior Written Consent Of The Publisher, and (2019), which you showed at 421 in Abu Dhabi.

I decided to show papers that my mom kept. She documented everything, from when it was going to rain to collecting stamps or what happened to us. I asked her if I could make a work alongside her text and documents and she agreed, but was always saying: “You’re crazy. What are you doing?” She basically just wants to see me making landscapes. My mom stopped writing and documenting in 2001 because of her responsibilities and everything that had happened. She had to be a man and woman at the same time, especially when we lost my father, and after the [US] invasion we were searching for his body in hospitals, farms, abandoned gardens. It’s a tough process. We forget faces. We didn’t see our own faces for a year in the mirror, but when we moved to Baghdad the first thing my mom did was to take us to a photographic studio to have a family picture taken. She’s a really strong woman. I ended the title with “and” because there is a story creating itself. It’s out of control.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 106: Making Their Mark