Staged across Lisson Gallery’s duo of London locations – on Bell Street and Lisson Street – Matter as Actor is an elegant and contained exploration of the relationships between humans and material.

Curated by Greg Hilty, this is an exhibition invested in exposing and reflecting linkages between people and objects at multiple levels. It rises like an aria to comment on how these connections are tipped towards humankind’s age-old colonial impulses – to discover, plough, extract, distort, destruct, rename, erase. The show’s very title is the quietest smirk, at us – what happens when we stop seeing ourselves as the drivers of the plot, and succumb to centring what has always preceded us – land, matter itself?

Hilty, both in person and in his curatorial statement, professes anthropology as a key influence, particularly citing anthropologist Tim Ingold: “The properties of materials…are not attributes, but histories.” Even when inverting the balance between human and matter, questioning where agency is really located between the two, the exhibition’s approach is steadfast in not just presenting a series of curated artworks-as-objects, but in largely insisting upon the story and context behind them.

Any audience can feel the insistence of the wide geographical span of artists. Twelve of them, comprising individuals and duos – Allora & Calzadilla, Dana Awartani, Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen, D Harding, Irmel Kamp, Syowia Kyambi, Richard Long, Otobong Nkanga, Yelena Popova, Lucy Raven, Zhan Wang, Feifei Zhou – represent widely disparate cultural backgrounds, from Saudi Arabia and China to Puerto Rico and the USA, Kenya, UK, Germany, Belgium and Australia.

© Otobong Nkanga. Image courtesy Lisson Gallery

Anthropology as a discipline is rooted in colonial history, beginning as the systematic discovering and chronicling of foreign objects and people. And while the deliberate choices of this varied line-up might initially appear like a detached ethnographic exercise, with each artist becoming a token representative of their roots, the careful, considered way in which they are exhibited renders that assumption mostly unfair.

Sometimes, there’s the minor excision of context. Kyambi’s Entity Costume, her worn outfit from her 2011 Fracture performance series, is presented on its own as a kind of “sculptural object”, Hilty explains. It is made with tea- and coffee-stained fabric, cowrie shells, beads, paint, clothes hangers, and sisal constructed using the Kamba weaving method, typically used to make local handwoven bags or kiondos.

Kyambi’s artful creation alludes to a “juxtaposition” between the local knowledges carried within Kenyan handicraft traditions and British colonial history in Kenya, which created immense dispossession and the disenfranchisement of the Kenyan people and what they make and produce on their own.

Where curatorial strategy really soars is with certain works by artists who are from, based in, or commenting on the human impact on non-Western lands. In D Harding’s case the suggestion is that some ‘Western’ lands were only made Western through the erasure of their indigenous people and the consequent splicing of their histories. The particular shine of such works ends up foregrounding, albeit subtly, the link between Western modernity and human destruction, leaving ghastly results for poorer or weaker countries. It also tolls a bell for the global climate crisis, helping to give the show that necessary climate-focused bent that any narrative on material today must confront.

This is especially apparent in the room populated by Zhou’s and Nkanga’s works. The latter’s arresting mixed-media installation Solid Maneuvers (2015), accompanied by utterly magnificent tapestries and photographs presented on sculptural posts, serve as commentary on the impacts of mining in Namibia – which have left permanent scars on the landscape – while expanding into larger meditations on the physical and mental consequences for both human and environment in the quest for economic expansion.

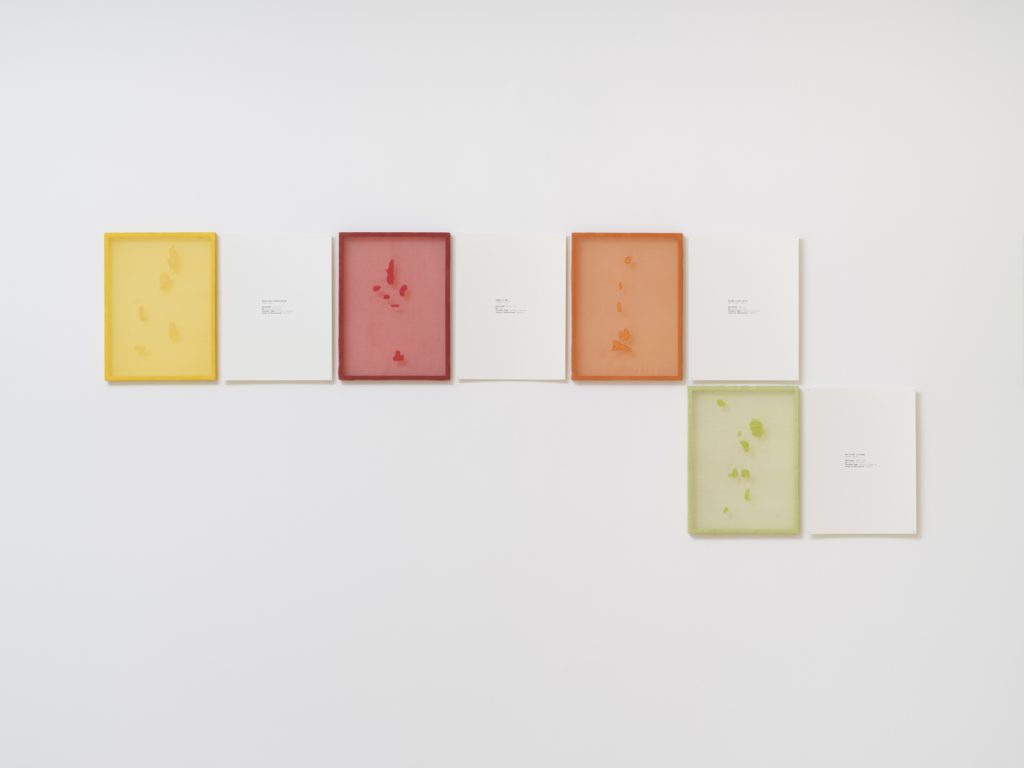

Dana Awartani. Let me mend your broken bones 4. 2023. Darning on medicinally dyed silk and paper. 8 parts, each: 27 x 36 cm. Overall: 74 x 198.4 x 2.5 cm.

© Dana Awartani. Image courtesy Lisson Gallery

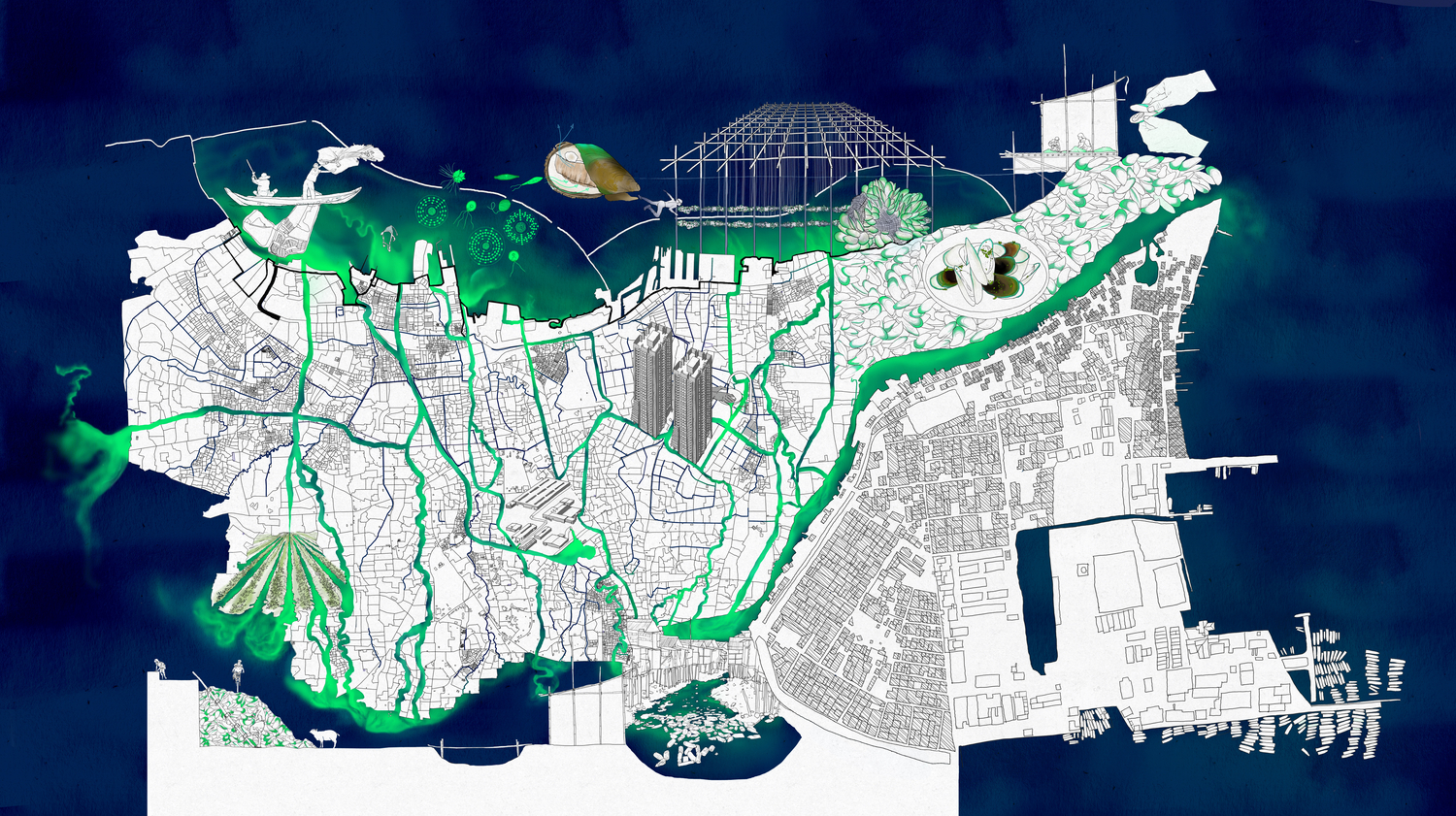

Meanwhile, Zhou’s sprawling, drawn and digitally printed wallpaper work Flowing Toxins (2020) maps and manipulates the cartography of Jakarta, demonstrating how industrial infrastructures for water supply, sewage, property and the mussels industry produce massive urban inequalities while polluting and disrupting local ecologies.

Every work is ultimately imbued with a palimpsest of commentaries, making Matter as Actor a show to approach with the patience of meditation almost, in addition to diligent inquiry. Nowhere is this most salient than in Dana Awartani’s Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones, as we stand here mourning (2019). The work is as pastoral as its lengthy title, yet equally rigorous. Handmade, naturally dyed silk fabrics from Kerala are infused with herbs and spices used for medicinal healing in both South Asian and Arab cultures. Yet the fabrics contain tears and punctures, representing various violent incidents enacted by Islamic fundamentalists, each powerfully named next to each textile. Awartani takes the layers further, darning and embroidering over these fissures to the fabric, as a literal and metaphorical repair act. It’s a work that reminds you that yes, we have hurt so much – the land and each other – but we can always, also, act differently, to heal and redress the ruptures.

Matter as Actor runs until 24 June