The exhibition Soul Mapping at Antwerp’s Zeno X Gallery explores the dichotomy of appearances versus reality, prompting reflection on what actually makes a painting figurative.

Paintings can either fill an entire room, drawing the audience to them, or fail in their attention seeking, and Zeno X’s current exhibition Soul Mapping, one of its last, is akin to searching for something. Taking its title from one of the works exhibited, Soul Mapping spreads across spaces, in central and south Antwerp, with works that are flat and facing out from the walls of the galleries, like stills from home movies, and which punctuate the all-around grey and white. It is a matter of deciding what to watch. If you believe it strongly enough, the figures that inhabit these past and present works conjure the characteristics of people in our lives. Less convinced, they pollute one’s imagination, like everything visually accumulated on the journey to the gallery.

Inside, if colours can capture an audience, Marlene Dumas’s Portrait of Jack Whitten (2023) is satisfying, not least for the artist’s assured ability to introduce us to the image as emblem, an ever-present motif throughout the exhibition. Dumas’s signature style, and the work’s prominent placement, are reflective of a countrywide faith in figuration. With painterly paintings and brushstrokes that caress the canvas like coloured ice cream, they create something of reality that we can fix on. Dumas’s close-up of a face painted imperfectly offers more than the nuanced paintings of Miriam Cahn, as her figures – Soldat (1997) and Roh (1998) – dissolve into the background like spirits, yet appear able to bury one with their presence. Sexual and sexless, Cahn’s works intentionally remain anonymous, if Dumas’s man is known.

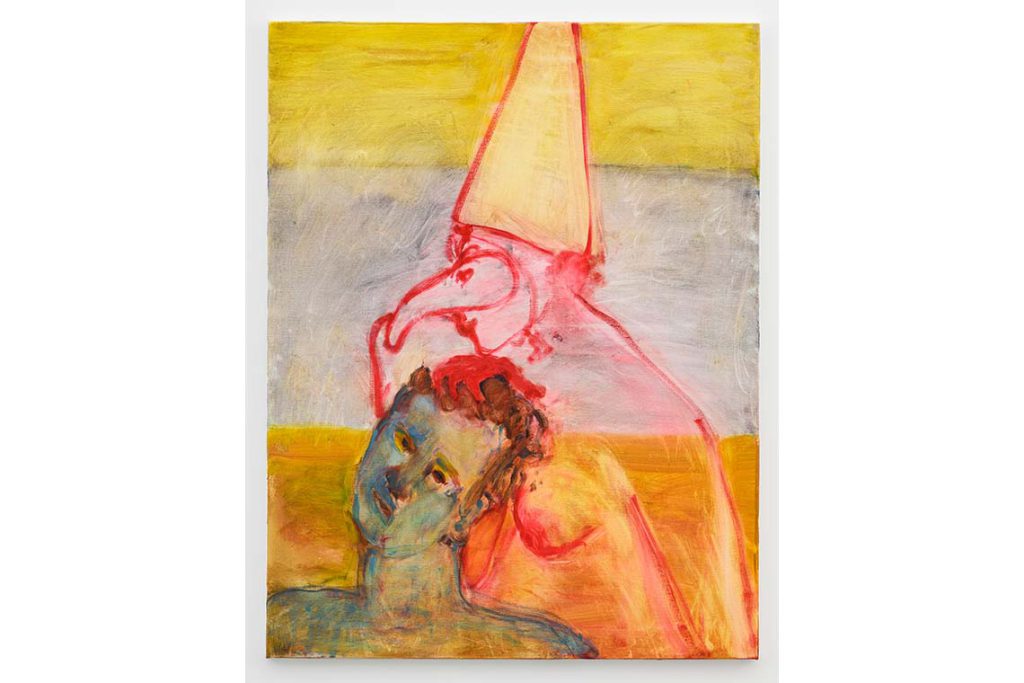

Rosalind Nashashibi. Punch in Love (She’s Getting Stronger). 2023. Oil on linen. 110 x 85 cm. Photography by Damian Griffiths and Peter Cox. Image courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

Whitten himself has a canvas in two parts, like technical photographs, which are obscured and as much visible, surveillance of a landmass that has been outlined, in a country at peace or showing signs of a conflict. Composed of a blank white space that cuts to black, Soul Map (2015) is an overview made up of buildings from above. Mary Heilmann’s works The Glass Bottomed Boat (1995) and Johngiorno (1995) are careless but equally considered paintings that conjure the atoms and anatomy of the modern experience, as she intentionally paints details that ping against one another before dissolving into the background. They are paintings that hold their own almost 30 years later, borrowing as much from (Piet) Mondrian as they do (Kazimir) Malevich. Not too far away, Rosalind Nashashibi’s Punch in Love (She’s Getting Stronger) (2023) is as spirited, as she paints a combination of figures that appear as much at play as they do the prisoners of the colour-coded canvas. In one of the stand-out works in the exhibition, Nashashibi appears to relish the lack of reasoning behind her work.

Sanya Kantarovsky’s oil on linen Father (2023) could well be the aftermath of Nashashibi’s punch-drunk scene, as the face of the figure appears paralysed by what is the unknown. (Egon) Schieleesque, ball-bearing eyes ready to leap from their sockets, as much as the blackened hair leaps from the forehead. Its horror conveys an incredible urgency, something lacking in the other works. Mounira Al Solh’s She Woke Up the Radio (2022), Passion Teapots and the Birth of Al Hamza, On Fire (2019) feature caricatured figures that revel in song and rise from and reach for the floor, body bent double. Solh’s works are unconventional, crazy even, for her deciding in the moment the direction that her paintings take.

Mounira Al Solh. Passion Teapots and the Birth of Al Hamza, On Fire. 2019. Oil, charcoal, pencil, pigment and turmeric on canvas. 119 x 171.5 cm. Image courtesy of Zeno X Gallery, Antwerp

At Zeno X’s second space, there are works by Luc Tuymans, Raoul De Keyser and Salman Toor, as well as abstract works by Strauss Bourque-LaFrance, among others. Tuymans’s characteristic softened strikes of colour imply objects and individuals that litter modern history and that by his choosing he can elevate to immortality. Happy Birthday (2023) could be a floating turtle as much as a deflating balloon, its meaning a mystery; and that secrecy, the search for something to explain what we are looking at, is as evident in Salman Toor’s Loincloth Man (2023). A painting that positively resonates with everything in this exhibition, from the figure’s comical awkwardness, red nose attached, to his ineffective idleness as it reflects the inertia of many of the exhibition’s illustrated figures; their silence giving nothing away. These are paintings that rid themselves of the reasonability of being faithful to reality, instead ridiculing it, until the surreal and the absurd rise to the surface.

The gorilla fingers of Toor’s Loincloth Man, as well as arms that show evidence of the artist making up his mind, extend the idea of the impassive, here at the point of unemotional exhaustion. Offering little in the way of character and clothing, the scene still impresses upon one an inescapable honesty. In the artist’s hands, and those of his contemporaries, painting continues to be reinvented, by leaving so much of the world out, in the way that in his day (Diego) Velázquez isolated figures against grey and greenish backgrounds to elevate their stature. Toor’s cloth-covered man is as much angel as potential anarchist. These paintings, concentrated on the figurative, are seductively sparse for all the space painted into them, making them less crowded, lavish even for their lethargy, but equally less convincing.