The exhibition Half Light at Grey Noise by Fahd Burki marks a departure from minimalism, delving into studies of colour, space and form.

Over the years, Fahd Burki has intentionally maintained a reluctance to provide a fixed narrative for his art, leaving it open to interpretation and devoid of contextual constraints. “For me, painting is much like a piece of music,” he says. “When you listen, the first question that arises is not: ‘What does this mean? It’s a feeling I’m trying to communicate, one that’s captured through colour and form, just as music is heard and felt.”

While this deliberate ambiguity sparks curiosity and raises questions, exploring the influences shaping Burki’s perspectives allows for a closer understanding, especially within the context of his latest exhibition, Half Light. Coming of age in Lahore during an era marked by the exchange between globalisation and local nuances, Burki’s worldview bears imprints of both colonial legacies and Mughal traditions. His education at the National College of Arts, founded by the British Crown in 1875, accounts for the draughtsmanship evident in his practice. Additionally, his association with miniature painter Murad Khan Mumtaz, a friend with whom he shared a studio, immersed him in traditional artmaking.

Burki’s early exposure to mainstream English literature, amid an independent media revolution, immersed him in a world of fantasy, science fiction novels and English-language comic books. Eclectic influences from Hollywood, MTV culture, post-war sci-fi and Japanese anime, coupled with his local experiences, contribute to a unique understanding of the world embedded in his work. The artist’s non-art interests, spanning video games, folklore, psychoanalysis, cults and the occult, religion and ritual, as well as minimalist musicians like Hiroshi Yoshimura, equally find embodiment in his practice.[1] “I can’t say that pop culture has left me,” he reflects. “It is, after all, the way that I think about images. Even if I’m not directly referencing it, someone will walk past a work and spot something familiar, a little tiny element reminiscent of sci-fi, but I’m not actively pursuing this anymore. I’m looking at painting purely in terms of my engagement with medium, texture and canvas.”

The diverse influences shaping Burki’s earlier compositions are characterised by flattened graphic iconographies, the eye of a cyclops or an inverted triangle, as well as opaque robotic, architectural and anthropomorphic forms. Over time, these symbols have undergone a process of increasing simplification, leading to a significant shift in his artistic approach by 2019. This period marked Burki’s embrace of a reductionist methodology, focusing on concepts of absence, balance and relief.

While his practice resists a specific, easily identifiable signature, it is better understood through particular ‘moments,’ bound by a shared commitment to a rigorous conceptual and stylistic orientation. In this latest body of work, Burki converges these nuanced understandings to unveil a more representational turn. Burki acknowledges this shift, noting how “These days I’ve been drawn to a freer approach to painting,” marking a change in visual language and a return to experimentation with large-scale pieces for the first time in more than a decade.

Inside Grey Noise, just five works are displayed, allowing for individual appreciation akin to encountering a single piece of art within a chapel. “I consider them unresolved thoughts,” he says. “They’re dreams; images that have been stuck with me for a long time. Sometimes as a painter, it’s good to put stuff out there that isn’t completely resolved, you don’t need to know everything about the image.” Titles tend to offer clues to Burki’s otherwise ambiguous intent, apparent in earlier works such as Liar (2012), Lullaby (2010), Optimist (2012) and Each to their own (2009). Untitled – Passage (2023), the first piece greeting visitors, captures a transitional state – a liminal moment between day and night. The artist incorporates a step gradient in several works, achieved by layering paint washes one upon another. Here hues progress from a light grey exterior towards a darker core, suggesting the haze of dreams and enigmatic thought processes. While appearing flat from afar, the work encapsulates one of Burki’s preoccupations – the boundaries and potentials of his materials, achieved through a combination of gesso, acrylic paint and exacting pencil lines.

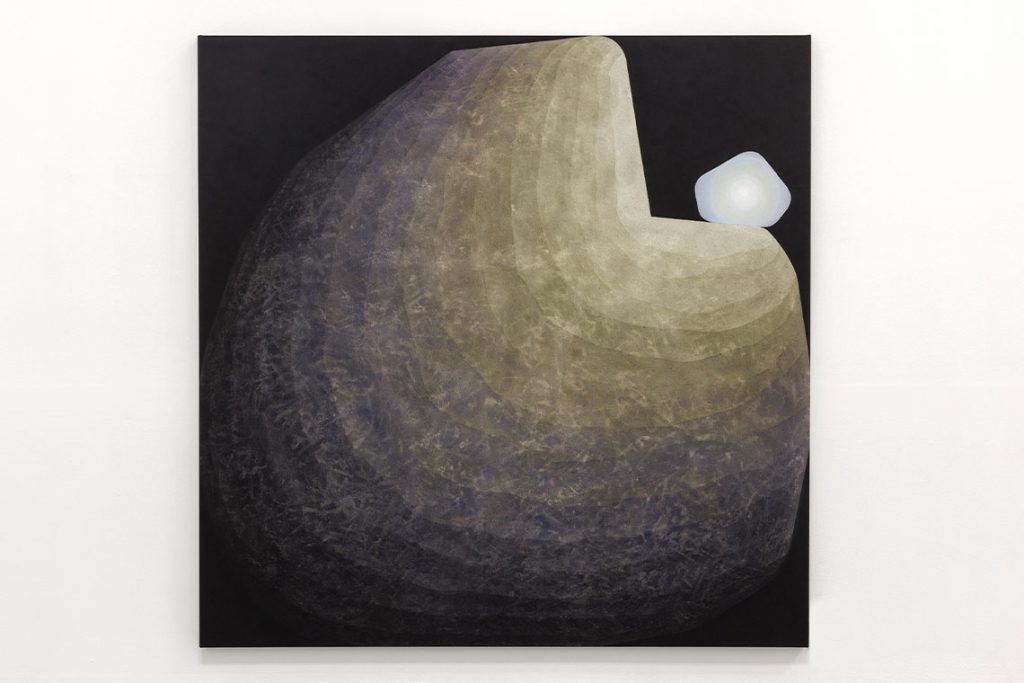

His otherworldly interest is evident in Moonstone Boulder (2023), where a glowing stone is captured with precision against the night sky, speaking of the alien or perhaps the ancient. In this exhibition, each piece – including a floating work on paper – carries its own visual weight, emphasising the physicality of Burki’s art.

Deep Blue Assembly (2023) and its preparatory paper sketch confront each other, employing a gradient of deep blue acrylic that conveys a sense of a particular moment, twilight, captured through arched brushstrokes. The silhouettes at the bottom of the canvas resemble urns, candles or a city skyline at night, inviting the audience to engage in interpretation. The final work, Moss Glow (2023), a large-scale canvas, evokes ideas about night vision, video game aesthetics and aerial typography. It can also be read as a study of the hue of green, shifting from a shade resembling an analogue Nintendo screen to the deepest tone, almost black from a distance.

These works, rooted in ambiguity rather than suggesting a specific context, leave room for personal interpretation. They remain uncertain. Are they reflecting upon past mythologies, anticipating a future or revealing an escape into fiction? Burki maintains that his recent work forms a quest to unravel personal enquiries: “The fundamental question of why I engage in painting propels much of my exploration,” he posits. “Why not transition to AI, graphic design or printmaking? What relevance does traditional canvas painting hold in our contemporary era when modes of image making are so diverse and readily available?”

In a world that often favours clear-cut compartments, Burki contends that artists should exist beyond neat categorisations, sparking a reconsideration of conventional boundaries. Each of us exists as a product of cultural, philosophical and technological currents, yet Burki distinguishes himself through meticulous precision, a deep grasp of materiality and conceptual enquiry. Through his practice, he urges us to consider why he should be confined to narrating a specific context or moment in time.

Half Light runs until 3 February

[1] Ansari, S. (2022) Borrowed Monsters: Popular Culture and Worldbuilding in the Works of Fahd Burki, Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, UAE.