In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine at Sharjah Art Foundation seeks to uncover truths that lie beneath official discourse about Israel’s war on Palestine.

Edward Said, in typically elegant and pithy prose, put it well: “The question of Palestine,” he wrote in his 1979 book of that title, “is the contest of an affirmation and a denial.” The most recent phase in Israel’s war on Palestine, ongoing since October last year, has seen a continuation of Zionism’s long history of refutable claims to justify occupation and war crimes, beginning with the notion that the region was “a land without people” on the eve of the movement’s arrival in the mid-20th century – what historian Illan Pappé has called one of its “foundational myths”.

A copy of The Question of Palestine – along with other resources on Palestine from Sharjah Art Foundation’s (SAF) reference library – can be found in a quiet, airy reading room within the Arts Palace in remote Al Dhaid, as part of SAF’s collection exhibition In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine. Said’s classic is accompanied by Rashid Khalidi’s The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine (2020), Noam Chomsky and Pappé’s On Palestine (2015), Walid Khalidi’s Before their Diaspora (1984) and other titles, which readers can pluck from stacks arranged around the intimate salon furnished with sofas, ottomans, lamps and a coffee table on a large patterned rug.

In conversation with the artworks unfolding around it – within the Palace and the neighbouring Old Al Dhaid Clinic, two off-site locations activated for Sharjah Biennial 15 – the space acts as an urgent archive that bears witness to realities denied by the Israeli government and Zionist movement. Examples can fill pages on end, from Pappé’s other “foundational myths” to Israel’s present-day denials of targeting civilians, journalists and public infrastructure as well as intercepting humanitarian aid. Israel maintains its hold over the facts by enforcing communications blackouts within Gaza, destroying state archives and benefiting from US media and diplomatic support. International media has also been prevented from entering Gaza since the start of the war, leaving Palestinian journalists and social media reporters such as Plestia Alaqad and Motaz Azaiza to document the war with limited resources. With In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine, SAF joins this chorus of voices taking back control of the narrative.

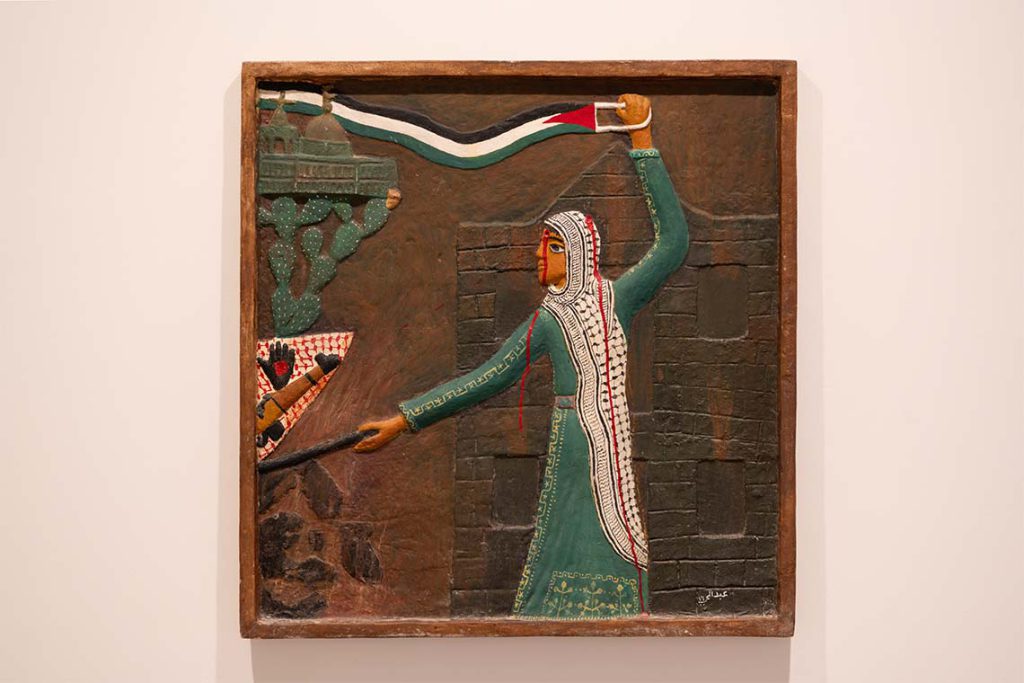

Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara. The martyr Abu Raja’a Abu Amasheh. 1976. Sharjah Art Foundation Collection. Photography by Shafeek Nalakath Kareem. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

Many works in the exhibition, including more than 60 from SAF’s own collection, can be thought of as archival and documentary art, inscribing a visual record of Palestine’s history and constituting an “affirmation” in the face of “denial”. Setting the scene in the Arts Palace is an extensive selection of 30 bas-reliefs by artist and freedom fighter Abdul Hay Mosallam Zarara, whose “archival practice” – as Alaa Younis calls it in his monograph published by SAF, also found in the reading room – documents events and images related to the Palestinian cause and other liberation movements, often drawn from memory. Political slogans, extracts from revolutionary poems and written narratives of assaults and massacres in the artist’s handwriting appear across the works, echoed by Simone Fattal’s The Rain Forever will be made of Bullets (2006) in an adjacent room. Taking its title from Etel Adnan’s poem Jebu – which tells the story of a pre-Israelite tribe from the land of Canaan, the Biblical name for the land west of the Jordan River – the work consists of basalt tiles painted with inscriptions naming the massacres of Palestinians since the Nakba.

The exhibition inclines organically towards video as a medium with incontrovertible documentary power. Standout works include Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri’s What Everybody Knows (2006), a title that reads like a retort to Israel’s strategy of misinformation. Seven screens arranged in a circle display a series of videos showing the daily lives of Palestinians under occupation, speaking to the importance of individual reports and oral histories in the face of an unreliable official register. Jumana Manna and Sille Storihle’s The Goodness Regime (2013) draws attention to the cracks in the façade of Norway’s image as a peaceful, humanitarian nation, solidified in the wake of the 1993 Oslo Accords mediated by Oslo-based peace institute Fafo. The film’s various sound bites from diplomatic speeches hailing the country’s virtues – such as former US president Jimmy Carter’s remarks at the Carter-Menil Human Rights Foundation Award to Fafo, in which he claimed the institute’s work was the “personification of the character of Norway itself” – feel incongruous in hindsight of the widely recognised failure, even counterproductivity, of the Accords.

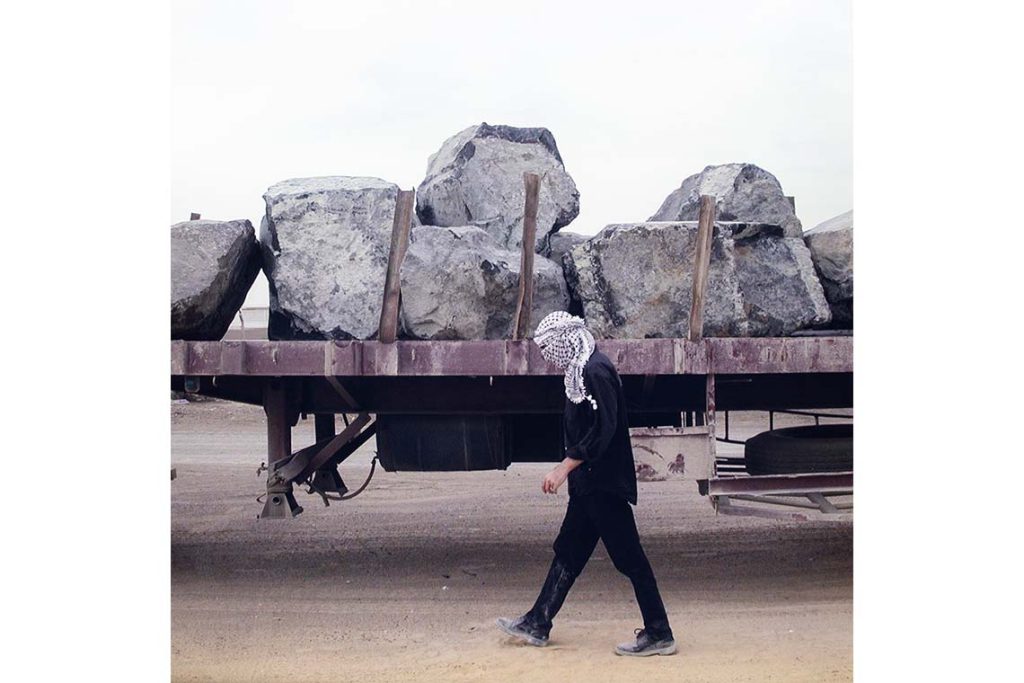

Tarek Al Ghoussein. Self Portrait Series. 2002–3. Photography by Danko Stjepanovic. Image courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation

As well as documentary art, In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine features a selection of works that explore the subject of documentation and historiography. Tarek Al Ghoussein’s Self-Portrait (2002–3), presented in the Old Al Dhaid Clinic, comments on the regime of images in Western media that associate Palestinians with terrorism. A series of lightboxes shows the solitary keffiyeh-wearing figure of Al Ghoussein in various isolated, sometimes sinister, locations: in front of a ship, between two targets at a shooting range, inside a meat locker lined with animal carcasses. As the figure’s only distinctive feature, the keffiyeh may lead some viewers to read him as a threat. In a 2004 interview, the artist recalls experiencing this himself while taking a portrait in front of the Dead Sea, when a Jordanian police officer took him aside for an interrogation that lasted 22 hours, asking “what was I doing, who was I, why was I wearing the Palestinian scarf, why that particular scarf – not the red scarf or the other type of black scarf?”

The refurbished clinic also houses Khalil Rabah’s Palestine after Palestine (2017), an iteration of his seminal Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind (2003–ongoing). Through fictional displays of the region’s zoology, botany and geology presented in the language of museology, the work challenges the authenticity of institutional documentation: naturalistic paintings of animals mimicking photographs; cross-sectional geological diagrams that upon close inspection also reveal themselves to be paintings; a collection of toy animals encased in glass; and a large, toy-like wooden ‘skeleton’ of a lion.

Like Rabah’s work, Kuwait-born Palestinian artist Basma Alsharif’s The Story of Milk and Honey (2011) blurs the boundaries between fact and fiction, raising questions about the nature of representation more broadly. The multimedia installation centres around a video-within-a-video in which the narrator recounts his failed attempt to write a love story as an allegory for Palestinian nationalism. In another layer of artifice, he tells us that, after the project had failed, he began to lie to others about its ending. In the context of the wider exhibition, the work reminds us that history itself is a form of representation: a narrative rather than a record.

In the eyes of our present, we hear Palestine runs until 14 April 2024