Rachid Koraïchi presented a stunning array of reflective and spiritual works that centred around a common message of universality and peace in his recent exhibition, Celestial Blue, at October Gallery in London

Nestled off the busy streets in London’s Bloomsbury, October Gallery opened Rachid Koraïchi’s sixth solo exhibition there, Celestial Blue, in style – speeches and photographers accompanied a palpable spiritual pulse as collectors, journalists and critics were engaged in deep hypnosis from Koraïchi’s latest presentation.

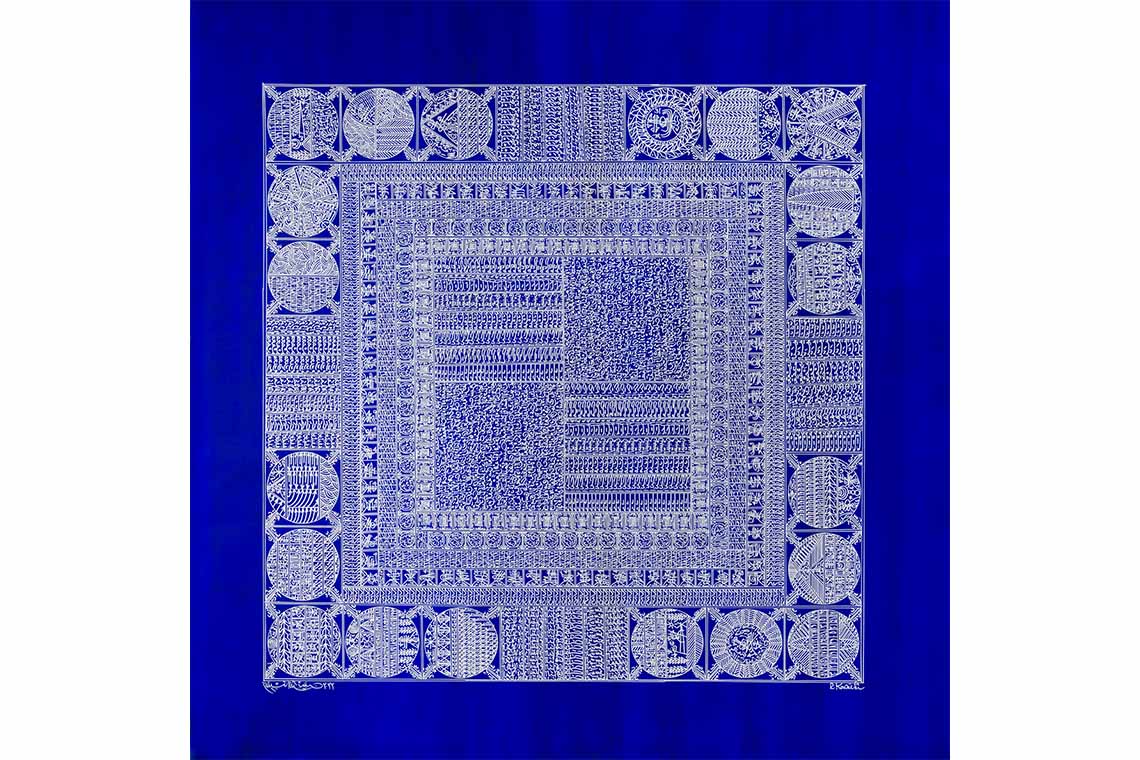

Entering the space, I was immediately confronted by large square pieces on every wall. Meticulously the same size, each work was seemingly staring at the viewer, drawing them in to examine the minutiae of Koraïchi’s signature style. Titled Les ailes bleues des Anges (the Blue of Angels’ Wings) (2022), the pieces draw inspiration from the 61 love poems (nasibs) found in mystic Muhyi al-Din ibn ‘Arabi’s Tarjuman al-Ashwaq (The Interpreter of Desires), published in 1215.

Koraïchi transformed the written poem into a visual form, interpreting one poem for each square canvas and improvising the spiritual and lyrical outpourings of ‘Arabi freehand rather than directly translating them. Distinctly geometric, each piece carries immense references: scripts, numbers, shapes and figures create a proto-language that blends archaic alphabets and Koraïchi’s own improvisations. A nod to the fusion of mathematics, language, script and figures within ancestral societies in Andalusia, Koraïchi’s hypnotic, abstracted language contributes to the repertoire of universal symbols that he hopes can inspire global connection.

Photography by Oak Taylor Smith. Image courtesy of the artist, Factum Arte and October Gallery, London

In creating Les ailes bleues des Anges, Koraïchi invoked deeply religious and spiritual overtones. Each square canvas is a direct reference to the Holy Kaaba while the deep blue background has been a consistent feature in Koraïchi’s work over the years, an allusion to the depths of infinite space and of invisibility. He notes how blue and white are the colours of life itself; like clouds passing through a deep blue sky, Les ailes bleues des Anges expresses a deeply rhythmic and spiritual transmission of emotion and hope.

Koraïchi does not begin with white ink on a blue background. Instead, he used a fine paintbrush and entre-de-chine on white paper, never with any prior sketches or initial design. The process of turning black ink on white paper into its inverse, white ink on blue paper, is undertaken in collaboration with Factum Arte, an added layer of intrigue and mystery to Koraïchi’s process.

In the middle of the room, engaging spiritually with the trance-inducing square canvases, were three large steel sculptures, part of Koraïchi’s Les Vigilants (2020). These three human-sized figures continue Koraichi’s long-standing interpretation of figures in sculptural form, either as representatives of everyday people such as the spectator, guardian spirits of a particular place, or pilgrims and prayers, depending on the installation.

Drawing from his previous projects Garden of Africa (2021) and Garden of the Orient (2005), the sculptures blend human and script, a metallic interpretation of the free-flowing emotions surrounding them. As if memorialising the emotive language of Ibn ‘Arabi through sculpture, the three pieces centered Koraïchi’s dedication to invoking ancestral ways of being and thought, both his own ancestors and ancestral community leaders.

Image courtesy of October Gallery, London

The last piece in Celestial Blue was a rather understated ceramic vessel from Koraïchi’s 2019 series Lachrymatoires Bleues (Blue Lachrymatory Vases). Placed between two canvases, the vessel is a ceramic interpretation of ancient lacrymatories, also known as tear vases, found in Roman and late Greek tombs. A continuation of Koraïchi’s methodological connection to the Mediterranean basin, the vessel is covered in his proto-language in the bottom half, with the top section featuring four handles and Arabic script and medallions, featuring poetic expressions of love and grief.

As I circumambulated the gallery in a spiritual way of my own, hypnotised from canvas to canvas, the three sculptures seemingly watched over me, just like the ancestors present throughout Koraïchi’s practice. The experience felt deeply meditative – background conversations and noise disappeared as I examined the script and figures of each piece. The emotive transmission was noticeable; the works harmonised in their hypnotic detailing to pass on Koraïchi’s core message: the universal applicability of the symbol and script, both with deep connections to the Mediterranean and ancient Islamic thought. Far from the oft-politicised religious practices of today, Koraïchi intervenes in religious and spiritual thought by hypnotising us, teleporting us back to communities saturated with peaceful and tolerant coexistence.