Harnessing visceral power with carefully crafted finesse, the artist reimagines the character of textile in his stone and marble sculptures.

“Textiles have traditionally been used in European art history to signal virtue and power,” says Reza Aramesh, the London-based Iranian artist whose work, across many media, features outfits of benign and oppressive varieties. “I find that my use of fabric speaks more of processes to reveal a kind of reckoning, which may hide underneath such opulent folds of luscious textile.”

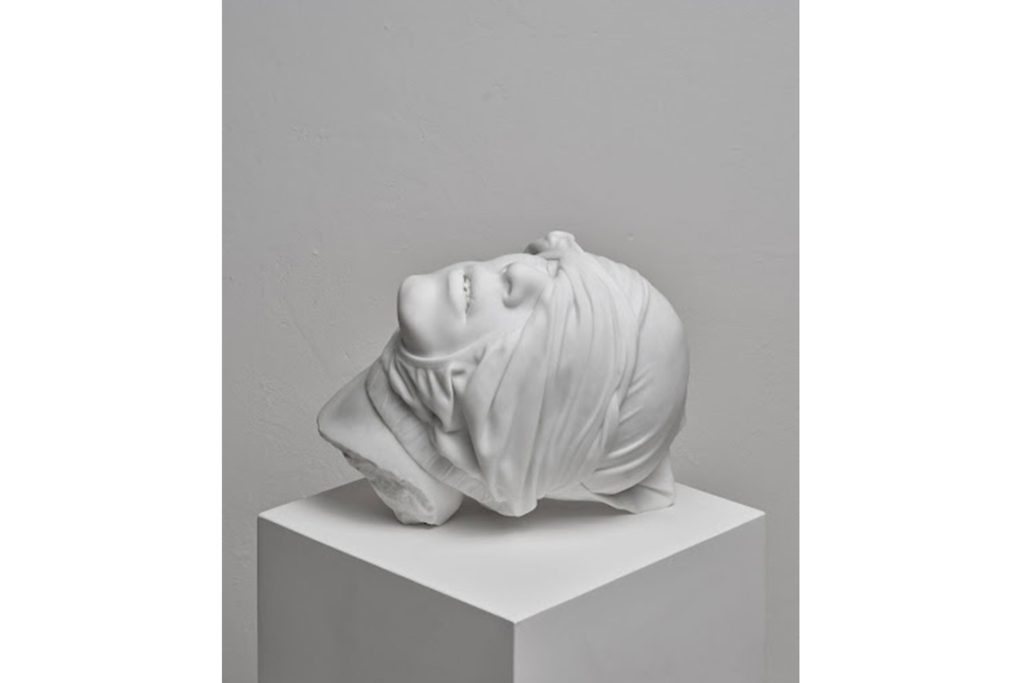

For two decades, Aramesh has melded together – in sculptures, ceramics, textiles, video, performance and photography – disturbing and aestheticising aspects of contemporary war reports with formats and customs inherent in Eurocentric art history. This is perhaps most evident in his marble and limewood sculptures of conflict-ravaged figures, bodies styled like classical heroes but cloaked in modern dress and hooded, blindfolded and bound like captives in rolling news footage.

Talking to me from Venice, where he was installing a new exhibition in San Fantin Church, Aramesh explains that his subjugated figures “reveal desire and beauty through the act of living through violence, or put more bluntly, the promise of violence.” It is a simultaneously disturbing and incongruous context for beautiful ripples of textile created out of stone and wood. Elegance and atrocities are bound together in his art. “The history of art and the history of war have always been melded together, especially European history of art, which was compelled to manufacture beauty in the service of power,” Aramesh notes. “I have built a vast archive of war reportage imagery, stemming from the mid-20th century to the present and these images provide the sources for my practice.”

Installation. Size variable; Site of the Fall – Study of the Renaissance Garden, Action 218: At 8:26 pm, Thursday 16 November 2017. 2024. Hand

carved and polished Carrara marble. 100.5 x 72.5 x 250 cm. Photography by Luca Asta. Image courtesy of Reza Aramesh Studio

Aramesh chronicles his practice in terms of ‘actions’, with individual works representing a numbered action: “I began with Action 1 in 2002 and I think it is something like Action 500 now.” The term also implies a positive engagement with the subject matter, rather than a passive stance. His Venice presentation, NUMBER 207 – curated by the Ugandan writer and curator Serubiri Moses and supported by MUNTREF in Buenos Aires and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami – aims to place his works “in a conversation between the contemporary states of the human condition in relation to the historical architecture of the space itself.” San Fantin Church, which sits next to Venice’s celebrated opera house La Fenice, was historically where the Order of San Fantin comforted the condemned on their way to execution.

“The works that I’ve installed in the space are in response to that,” Aramesh says. The exhibition includes an installation of 207 discarded items of men’s underwear, carved in white marble, “arranged across the floor and which signify the moment when a human being becomes a human statistic.” For Aramesh these garments represent the last vestiges of a person’s dignity surrendered during the dehumanising process of imprisonment. Also, he says, these items of clothing are “connected to existing paintings inside the church on the crucifixion theme, where the loincloth of Christ is particularly prevalent. The installation is a contemporary response to this universally accessible theme.”

Photography by Stephen White. Image courtesy of Reza Aramesh Studio

Born in 1970 in southern Iran, Aramesh’s interest in art was evident from an early age: he would buy European art books from a secondhand bookstore near his school just to look at the reproductions of paintings. “As a child I joined a theatre group in Iran and art was also very much part of our activities,” he recalls. “But when my parents found out, I was given an ultimatum to give up my creative work in favour of a more traditional education. He later relocated to London, where new horizons beckoned. “I never looked back,” he says. “Many people left Iran for political reasons, but I left because I had no other choice than to make art.” He studied at Goldsmiths University in London, graduating with an MFA in 1997.

“I don’t see myself as a decidedly Iranian artist, I see myself as an artist,” Aramesh continues. “There is a lot of discussion around the diaspora and the stories that come with crossing borders and being challenged by cultural barriers, but I have always found that my personal experiences don’t necessarily service my artistic practice, at least not as a primary source in my approach to art. I am interested in providing universal access to the human condition and that requires a discipline that mostly resides outside of self-reference.”

Aramesh’s practice began with photography and the repositioning of conflict imagery inside opulent settings like Kenwood House in London and the Palace of Versailles outside of Paris. Subverting the bureaucracy of such art historical institutions occasionally caused a stir. “At Versailles they only accepted my proposal to bring in hired actors to re-enact the refugees that are seen in the final pictures,” he recalls. “But I went around shelters in Paris and engaged with genuine refugees instead, who we brought in clandestinely to participate.” In 2010 he was profoundly moved by his visit to The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture 1600–1700 at the National Gallery in London. He returned repeatedly to view the exhibition, connecting with its ideas of mythology around martyrdom. The experience later inspired a series of limewood and polychrome sculptures that he showed at the Asia Society Museum in New York.

Photography by Laura Veschi. Image courtesy of Reza Aramesh Studio

About fifteen years ago, Aramesh explains, he began broadening his practice, translating his archival material into tangible objects – sculptural items and figures, ceramics, embroideries – as well as working on sound, neon and performance pieces. This requires collaborations with artisans and workshops and finds him involved “with processes, from wet clay to soft silks, hard stone and painted wood to living people performing and interacting.”

His installations have ranged from sculptures influenced by the German Baroque artist Andreas Schlüter, and which were exhibited in Manhattan nightclubs in 2013, to ceramics of prisoners’ shoes presented at Leila Heller Gallery in 2015. Action 188: Metamorphosis – a study in liberation, his large 2017 bronze of a hybrid creature contorted like a resistant victim of torture, was shown at Frieze Sculpture in London. Other solo and group shows include exhibitions at the MetMet Breuer in New York (2018), SCAD Museum in Georgia Atlanta (2018), Akademie der Kunst Berlin (2016) and the 2015 Venice Biennale.

With the recent publication of a new monograph and catalogue raisonné, Aramesh has been reflecting on his career to date. “I am surprised how diverse my practice has become at this midway point without losing sight of that nucleus,” he observes. “Each material that I use is specific to the message that I try to conjure from the material. Sometimes the idea comes before the medium, while at other times the material speaks directly to the idea. It’s a precise practice though and my studio researches everything in detail. But let’s not forget that artists are the ultimate unreliable narrators. I am not a documentarian.”

While Aramesh’s projects have alluded to particular moments in particular wars – such as the American invasion of Iraq – he stresses that his work is not a commentary on current events in the Middle East, or elsewhere for that matter. Rather, it relates to the perpetual cycle of conflict and trauma and their representation, what he calls the “hegemony of beauty in the service of power”. He has been working with this theme for over two decades, “and every time a conflict zone opens up in the world, people tell me that I’m so current and so in tune,” he reflects wryly.