In Cipher at Gazelli Art House London, Pouran Jinchi and Ruba Salameh weave their respective ways through a kaleidoscope of abstractive displacement.

For all the depth and multi-dimensionality of what is implied by the works of Iranian-born Pouran Jinchi and Palestinian Ruba Salameh, the exhibition Cipher at Gazelli Art House is fundamentally flat. The lower gallery walls hold onto a choice of works that codify, by camouflage, what they have encountered. Likened to the doors of a home in the region, with a courtyard leading to a living room, eating area, kitchen and bedrooms, where the lives and individual stories of the families inside come from seeing and meeting them. So the surfaces of these two painterly approaches require unlocking, in order to begin imagining the testimonies behind them.

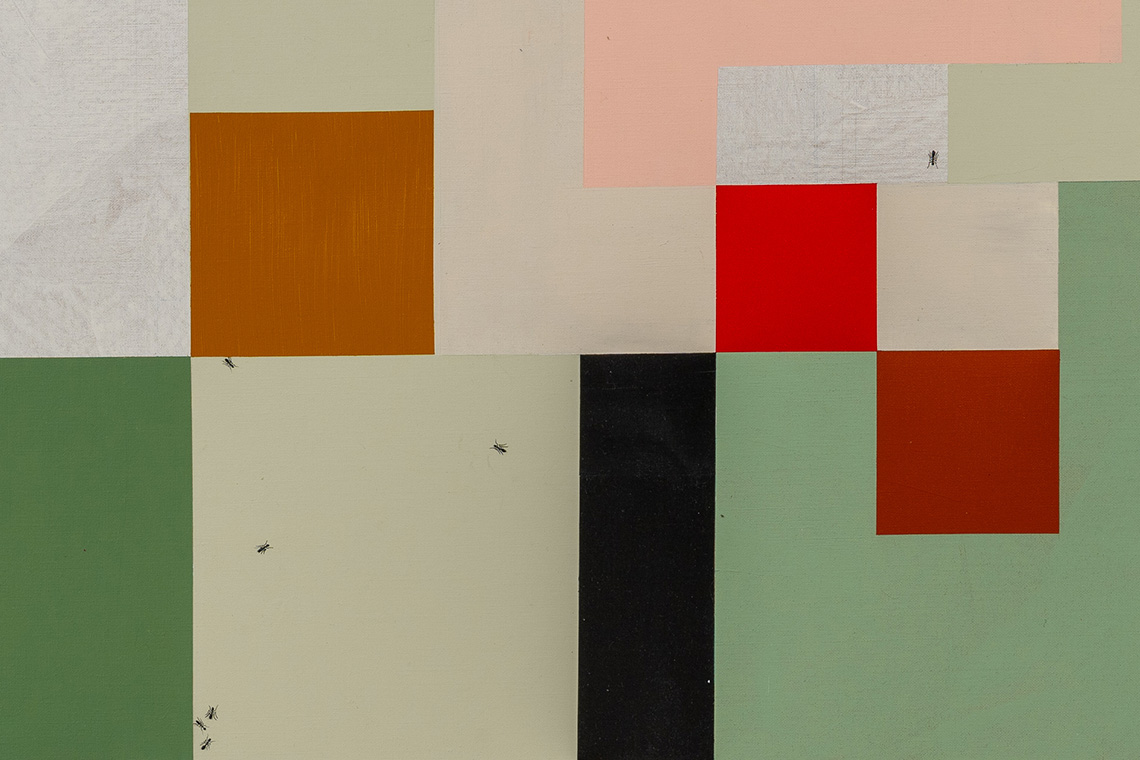

If Pouran Jinchi’s works are based on a longstanding interest in architecture and aesthetics, less human and more machine-like, Ruba Salameh’s paintings borrow all the big ideas of modernism, including Russian Constructivism, the German Bauhaus and American Minimalism. Movements that abolished figuration for a greater value in materials and colour. She explains her paintings as being open to interpretation, even if visually they appear closed, for the lack of physical and metaphorical space combined. Of their surfaces, she says that “the perspective here isn’t important, you could look at it in both ways, aerial or frontally. The main ideas and motifs don’t change. I refer to the canvas as land and the ants as indigenous people. These symbolise a collective identity that transpires through generations, one of displacement and loss of land. The structures and mapping that you see in the paintings represent the tension created by colonialism, and the insects are a people who, despite all, remain attached to their land and their inherent connection and devotion to it.” It amounts to figuration hidden under the weight of Modernism.

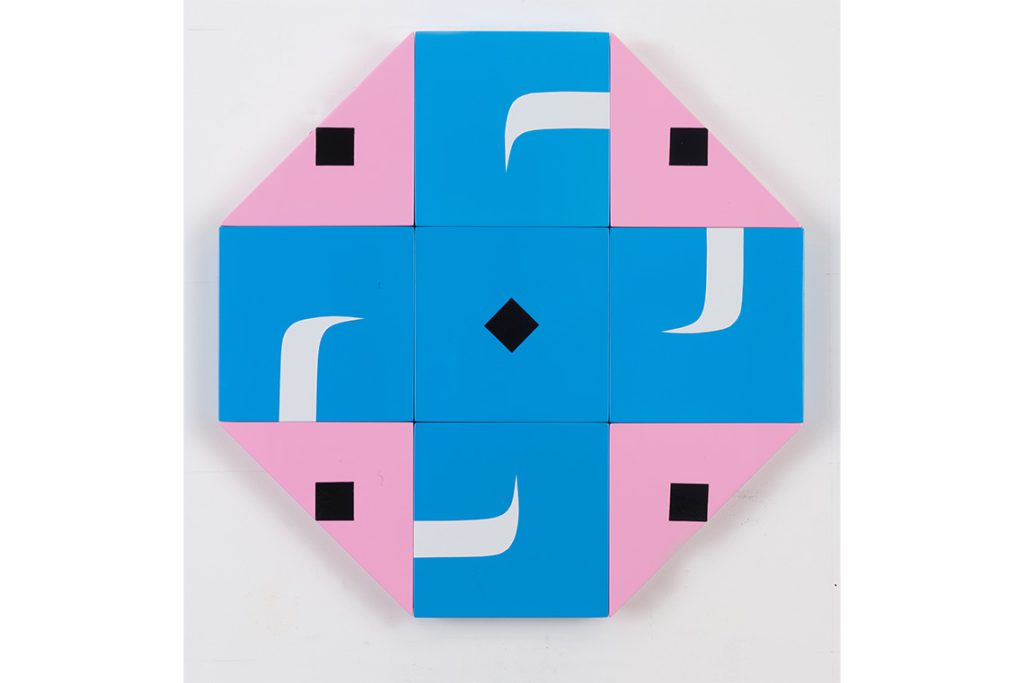

Jinchi’s enamel panels, illuminated by her choice of colours, engage in another kind of contradiction, of the sensibilities of calligraphy against abstraction. Emphasising how her work “plays with both sense and nonsense”, she explains that “I like to explore control through calligraphy and combine it with the freedoms of abstract painting. So, neither wins – they work together.” If only such political aspirations – control and freedom – could complement one another as easily as in her works. The mismatch is just as evident in Jinchi’s constructed conundrums, which in one has razor-sharp greens pressing against corner folds of orange and white; as in P as Papa Octagon (2017), and a similar arrangement with blues and pinks in B as Bravo Octagon (2017). Successfully managing to deconstruct the landmarks and a lifetime’s worth of memories, of cities and countries constantly shifting, under the weight of war and human displacement. She insists that “beneath the surface, my works address deeper themes such as war and conflict. The decorative elements may appear spirited, but they reference more serious symbols – like military insignia and camouflage – that carry great weight.” That surface appearing all too impressive, that the content comes from prizing open the individual puzzles.

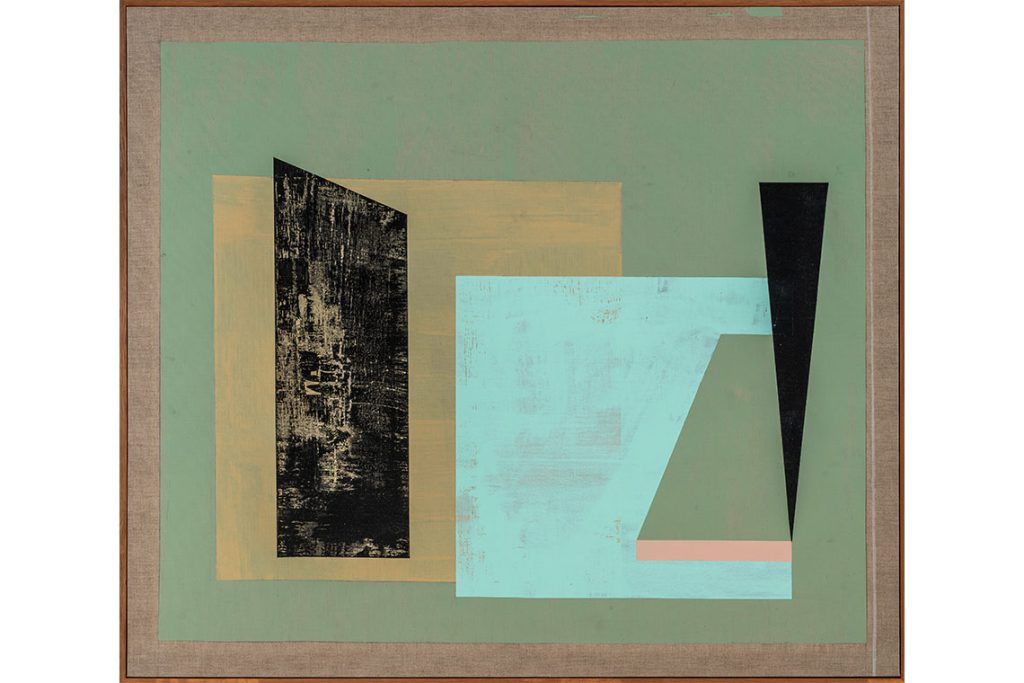

What is attractive about both sides of the exhibition is the artist’s use of colour, subdued by Salameh and electric in the hands of Jinchi, who introduces an intensity to her works that is as playful as she wants it to be seen as problematic. “Colour is important,” she clarifies. “In this series, I draw from military colours – camouflage, ribbons and flags. These colours add meaning and a sense of coding to the work, connecting the visual with deeper themes.” Meanwhile, Salameh’s works read like cubist paintings, particularly Composition I (2020) and Stripcle B.R.O (2020), as her compositions settle on the canvas like objects falling down an upturned table. Although the artist argues something simpler. “I see them as more minimal than cubist, Agnes Martin being an inspiration.”

Yet the sobriety of Salameh’s Martin-like backdrops is tempered by the intrusion of these almost invisible black dots, insects as she explains them, that rest on the paintings, interfering with their neutrality whilst giving them an earthly, rather than, otherworldly context. Carmel (2021) is the busiest of them all, a work riddled with colour, as a cityscape carries a small part of the world; reflective of the overlapping of land and lives, one upon the other. Go closer and you realise that Salameh’s paintings are not entirely in keeping with the aesthetics of Minimalism, as the colours are not entirely uniform, the shapes often irregular, and the inclusion of her signature dots serves as a reminder of the flatness of the surface; any perspective eliminated.

Perplexing but equally rewarding, the paintings explore forms delineated in different colours, representative of modern spaces, her dots the lives that infiltrate them. Salameh adds that “during the process of composing a piece, there’s always a dialogue between colours. To me a dialogue must include a contradiction, otherwise it will be boring. When choosing the colour palette, I put a group of colours that work together, and others that don’t, and my mission would be to find a connection within this constellation. Once that happens, I can call it a success. It’s rather a puzzle that needs to be solved in the eyes of the observer. Which eventually brings a harmonious outcome.” Jinchi, in her own words, admits to greater contradictions, saying of her works that her “influences come from both a background in classical calligraphy and the abstract art I studied in the West.” She notes also how “these two traditions might seem at odds, but they complement each other in my work.” Two painters who for their inventiveness have created visual codes to counter the real world.