Using a vibrant flow of imagery, the artist weaves a lyrical narrative that both beguiles and informs.

When Slimen Elkamel was a child growing up in rural Tunisia, his four aunts would tell him nightly folktales they had learned from their mothers and grandmothers. “There were a lot of aunts, and a lot of stories,” he reveals over WhatsApp video from Tunis, where he lives and works. Moved by their tales, he attempted to conjure something similar when he was 10 years old, using his own visual imagery. “I was trying to do what my aunts did through narration, but with drawing,” he says.

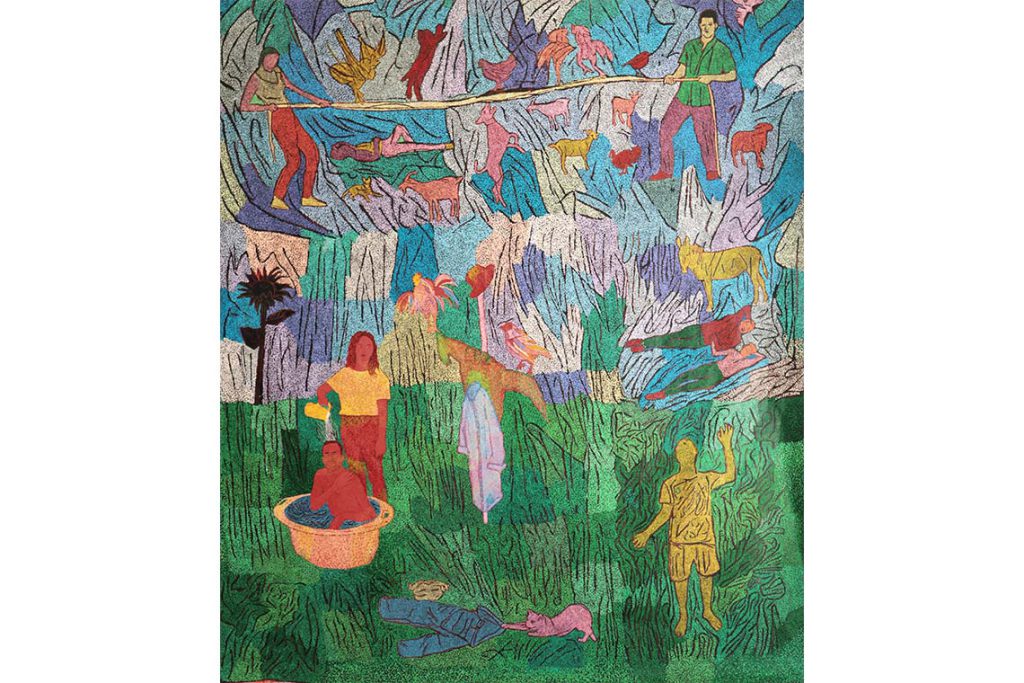

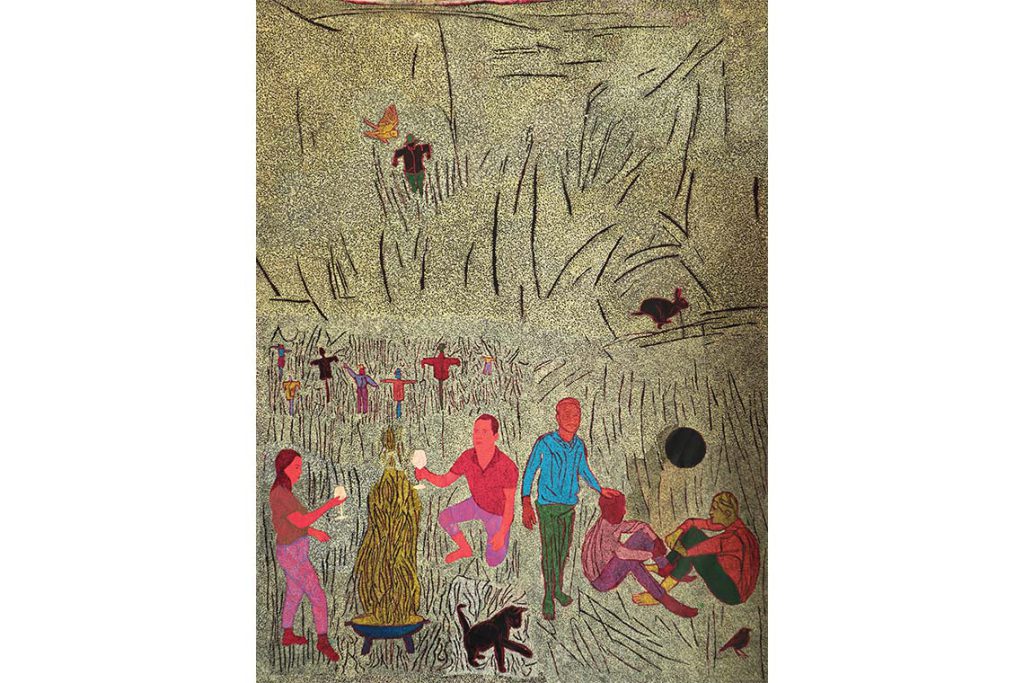

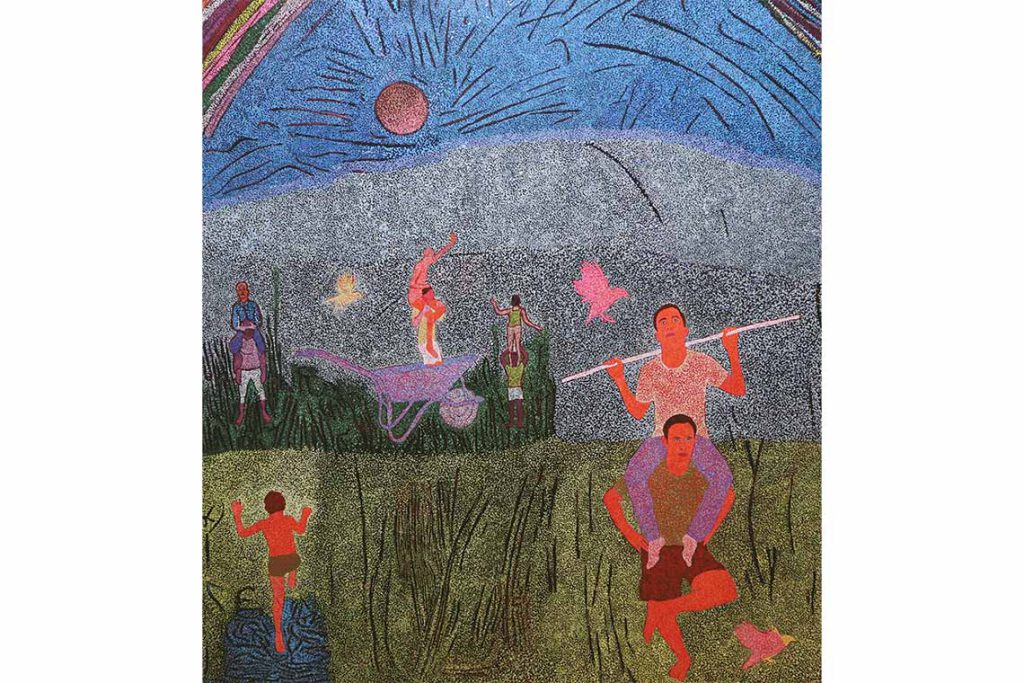

In a sense, the 40-year-old artist is still working to that end, although his practice has certainly evolved. The women-led, Tunisian tradition of oral storytelling, “influenced my personality and my way of seeing the world,” he explains. As such, it anchors his paintings, which ebb and flow within narrative and free figuration. People, domesticated animals, nature and landscapes float and interact in his paintings, while remaining intentionally detached from plot or directed meaning. Similarly, familiar and clear boundaries between forms are not what they seem. Outlines or shadowy spirits emerge the longer one looks. They overlap with more solid subjects, which pop from chromatic scenes rendered in Elkamel’s signature, pointillist marks made with acrylic pen on canvas. “There is no linear, anecdotal narration. It’s a kind of labyrinth that allows you to write your own story,” he offers.

Today, many more are able to do just that. Elkamel’s works have gained international visibility, making him one of Tunisia’s leading art stars. He was notably the subject of a solo exhibition, A Coeur Ouvert (With an open heart), at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris last year. The show was extended through two simultaneous exhibitions in the French capital, one at La La Lande Gallery, which represents the artist, and another at Nouchine Pehlavan gallery. His paintings can be found in the collections of the Museum of Contemporary African Art Al Maaden (MACAAL), Morocco; the Blachère Foundation, France; the Alain Servais Collection, Belgium; and the Gandur Foundation, Switzerland, among others. He is currently preparing works for a group show, Indigo Waves and Other Stories: Re-Navigating The Afrasian Sea And Notions of Diaspora, at Savvy Contemporary in Berlin, opening on 6 April.

Magical realism and Marc Chagall also come to mind as associations with Elkamel’s vibrant paintings. “I refer to the reality of daily life scenes to create a kind of fiction. The two – reality and fiction – inhabit the same space,” he says of his paintings, which he executes “like writing”, sitting at a table, the canvas laid out before him. He also works while listening to audio books, translated into or in their original Arabic. In fact, Elkamel admits that he dreamed of becoming a poet or novelist when he was younger and has held onto that impulse in many ways. For one, as a “warm up” before entering the studio, he makes a habit of going to a nearby café to write “flashes”, observations, poetry and other sketches. “I try to give a sense that there is a poet or a writer behind these works, pulling the strings, or directing a scene,” he explains.

To set that scene, Elkamel makes use of intense colour juxtapositions and manipulation. Their vibrancy may be the most immediately impactful aspect of his paintings and can take time to absorb in their detail and endless subtle shifts, like flickers of light. His chromatic choices, “are the expression of time”, he reveals.For instance, to give a feeling of midday, he will construct layers and shades reflective of the same time of day. His starry night scenes, on the other hand, will sparkle with darker shades, blues and purples. Elkamel has also said he makes his constellations of tiny, pointillist dots to the rhythm of his own heartbeat – and this, at impressive speed.

His method can be reminiscent of Tunisian mosaics, with their contained blocks of colour, as well as Arabic miniature paintings, with their flatness, composition and density. However, rather than intentionally referencing these sources, Elkamel says he is “inhabited” by his “underlying” cultural background. He has also belatedly discovered connections between his pointillist technique and indigenous Australian art, or even traditional Chinese acupuncture. “There are many connections, and not only with the Western heritage in painting,” he observes.

While a contributor to non-Western contemporary art, and hence to the making of new cultural heritage from other regions, Elkamel is not interested in representing his country for an art world 120121that would view him as a token ‘Oriental Other’, whose greatest merit, by inherent definition, stops there, or worse: answers to market demand. “In my paintings, I don’t want to say that I am Tunisian, African, Arabic – an exotic image,” he affirms. “I don’t want to be accepted within that box. I want to be an artist.”

Equal participation doesn’t mean conforming either, nor diluting what makes Elkamel’s unique body of work and voice, which is clearly marked by his heritage. On the contrary, he insists that diverse perspectives (he also writes art criticism), when listened to with equal measure and respect, are not only key to a healthy, egalitarian art historical discourse, but also necessary. “There are other ways of expression, other forms of resistance, and other voices that history needs. We have a duty to participate in the writing of global art history, and we do so on an equal footing,” he says. “I don’t have this vision that we are Africans with problems that you [in the West] don’t have. I think the opposite… We’ve shared wars, pandemics… And like everyone, we have the right to share in art, without limits. There is no division between the centre and those on the margins anymore,” he adds.

On the back of his successful career, Elkamel has been able to do his small part in breaking down divisions and spreading art to where it may be less accessible in all its alternative forms. He helps support his hometown of Mezzouna, where he has a studio and directs a cultural centre that is in its early stages of development. A portion of profits from his paintings go to the space, where he hopes to eventually launch an artist residency. The small town is one of the poorest in the country, explains the artist, and the daily rituals, celebrations and interactions of its people, including his family and friends, nourish the imagery in many of his works.

“The simplest acts of our daily lives are profound. They have depth,” he says of his subject matter. He also sometimes draws from photographs of friends and other “real people”, while revealing that he never thinks of “drawing portraits of celebrities,because for me, we can all participate in the writing of human history. Every human being has his own story, his poetry and authenticity.”

The concept is consistent with Elkamel’s left-leaning, progressive worldview, which the former Arab Spring activist depicted more overtly and regularly in older works, which also tended to be less colour-intensive. Earlier drawings and paintings, including transfers and rubbings, communicated in more clearly overt messages against consumerism, often symbolised by the image of a dominant television screen. Other, iconic, references seen in his paintings nearly a decade ago include loaves of bread and labourers. Now, Elkamel says he has “matured”, from that period of “trying to find myself”. Rather, he believes an artist, “must not be a spokesperson for a political party, but instead a spokesman for dreams, the unconscious.”

Yet Elkamel’s paintings maintain a socially provocative dimension, with their interest in our shared, common plight and the question of togetherness, as in: How and what it might look like to live and function together as a community. Although his last major Paris exhibitions spoke of the heart, effectively avoiding a notable political stance, Elkamel also says that he’s known among locals for speaking his mind on left-leaning issues that include LGBTQ+ rights and feminist causes. He also admits he can push buttons when it comes to openly debating his selfproclaimed atheism. “I tell people right out loud that we have the right not to be our parents … We’re here now, and can think in a free and individual way, so that we don’t reproduce our misfortunes,” he says.

Elkamel’s parents did not understand his decision to become an artist, which he said was partly motivated out of a desire to rebel. He attended the Higher Institute of Fine Arts in Tunis despite his conservative father’s objections, but with some of his financial support, along with that of his brother, and a grant. Growing up, he knew no professional artists, and it was not until a trip to Paris in 2010, and his first visit to art exhibitions, that he understood “the possibility of being a painter”, he said. Today his family is proud of how Elkamel helps those around him in need, and is clearly making a good living, although it’s not clear to them exactly how. (His paintings sell for between USD 12–18,000.) When asked what pushed him towards art school despite all the odds, he answers: “I’m not sure, but it likely has to do with me being a little stubborn.”

That doggedness is nevertheless well-intentioned. Despite his refusals to engage his paintings in political messaging, as he once did, Elkamel’s sensitivity to human struggle still orients his artistic production. “Through fiction, and narration, we can diminish violence a little bit all over the world. We need to tell stories, to dream,” he says, adding that the practice can also be a calming, therapeutic exercise. To illustrate this further, Elkamel refers to the regional folktale, One Thousand and One Nights, in which the young bride Scheherazade delays her own execution by seducing her would-be killer and newlywed husband, the ruler Shahryar, through her ingenious skill at telling him cliffhanging, never-ending stories every night. In order to hear Scheherazade tell him what happens next in the story, he cannot kill or live without her. In short: “Fiction is the only way to escape death andviolence,” concludes Elkamel, with a smile.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 107: Art Nomads