Through compelling aesthetic and technological investigations, the London-based research agency challenges official narratives and speaks truth to power.

When Gaza City’s al-Ahli Arab Hospital was hit by a missile on 17 October last year, it kickstarted an immediate and loud argument of blame assignation. At the top there was Israeli prime minister Netanyahu and his government claiming that responsibility lay with a misfired Hamas missile, while Hamas and many of those critical of the Israeli regime argued that it was a deliberate Israeli strike in response to the 7 October terrorist attack.

In the digital age, public politics is played out at pace, and while bodies were still being recovered from the rubble, social media erupted with claim and counterclaim, cementing pre-held beliefs and with little space for nuance. Videos of the strike were shared and analysed by amateur sleuths, trying to find evidence through grainy footage, triangulating architectural features to determine the direction from which the missile came.

In a world saturated with smartphones and mediation, such internet analysis is a common technique to critique acts of warfare as well as far-right violence and police brutality. It is a tactic which is not only down to an increase in technology and social media, but might also be connected to the work of Forensic Architecture (FA), an organisation that straddles the three fields of academia, journalism and art, deploying aesthetic and technological strategies to unearth violent truths from the noise and disinformation.

Headed up by British Israeli architect Eyal Weizman, FA has risen to prominence across all three fields, with a 2018 Turner Prize shortlisting – followed by the 2021 Golden Nica award at Prix Ars Electronica – cementing its work into the art world canon. Weizman, who has been presented with an MBE for services to architecture and elected as a Fellow of the British Academy, now oversees a network of more than 30 people within a suite of rooms at Goldsmiths College, London, as well as important connections to a global collaborative community of artists, activists, journalists and citizens.

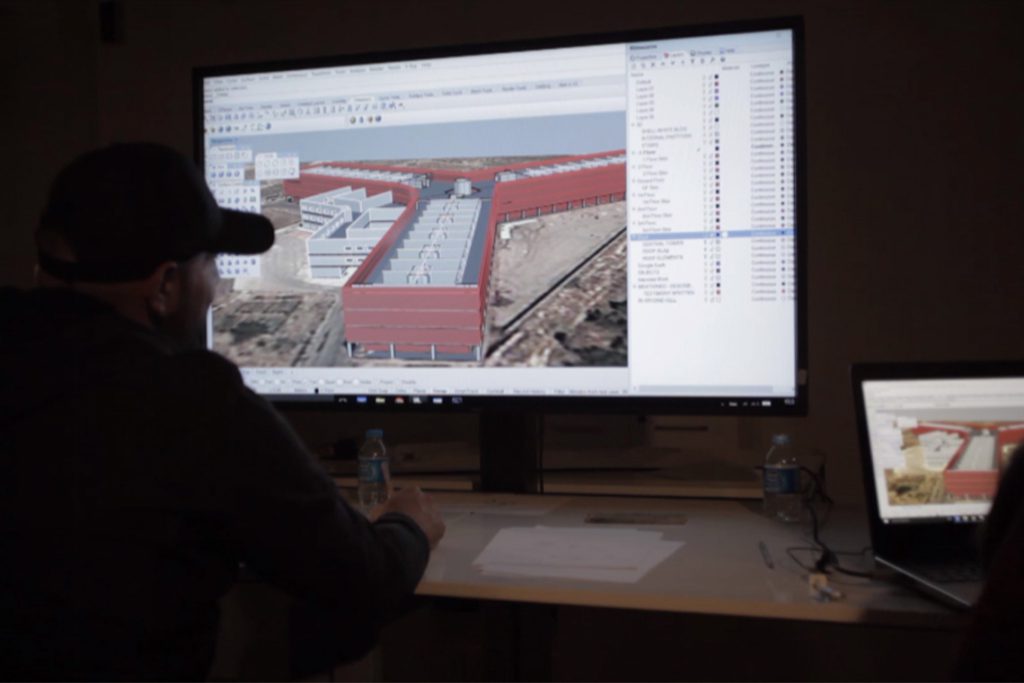

The FA website lists involvement in over 240 exhibitions since 2010, including several biennials and solo shows that include a major 2022 presentation at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Denmark. It was here that I met Weizman, ahead of the exhibition Forensic Architecture: Witnesses, which looked at how FA uses creative physical and 3D models within its processes. He explained to me how “usually a case would first involve presenting the evidence in court, then in the media, and then in an exhibition – with an exhibition being a place for reflecting upon our techniques, an opportunity for us to both create new audiences.”

The art world doesn’t offer FA simply a platform or route to these new audiences. Creative processes are a critical element of its multi-stranded research, with collaborative artists able to use their aesthetic and analytical skills in separate strands to their individual practices. For example, Lawrence Abu Hamdan – who was himself shortlisted for the 2019 Turner Prize, a year in which its competitive dimension was broken by all four nominees agreeing to share the award – has worked with FA on seven projects. These include FA and Al Haq’s 2022 investigation into the extrajudicial killing of Palestinian-American Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, a process that ultimately contributed to an Israeli admission of culpability. Hamdan worked on audio analysis that allowed FA to compare the sound signatures of fired shots, enabling the team to trace these to a specific marksman’s position.

Davide Piscitelli is one of the Goldsmiths team. Starting his academic journey with the intention of studying architecture, via a degree in New Media in Milan then a Masters in Material Futures at Central Saint Martins, London, he took up a position as advanced researcher at FA two and a half years ago. The organisation is formed of a mix of experiences and expertise from across the visual arts, academic scholarship, legal, scientific and architectural disciplines, forming a genuinely interdisciplinary approach. Broken into groups working on specific investigations, some of the FA team, like Piscitelli, float across projects applying expertise where needed.

Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, 2017. Photography by Tretter. © Zeppelin Museum

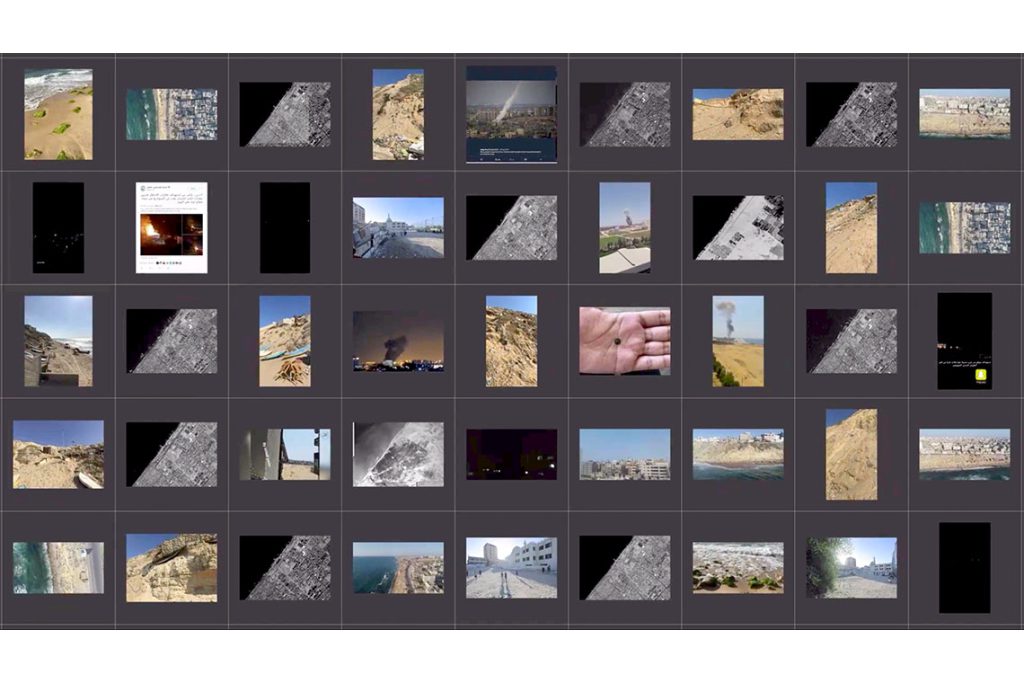

On 17 October 2023, Piscitelli was part of a group analysing immediate footage of the destruction of al-Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza. Initial outcomes were documented on FA’s thread on X (formerly Twitter) three days later, presenting a series of images, graphics and videos arguing for the likelihood that the weapon originated from the direction of Israel. It offers a good example of FA’s investigative approach: working with people and reports on the ground; utilising images and data sourced from social media; expert collaboration, in this instance war crimes investigator Chris Cobb-Smith, Al-Haq human rights NGO and sonic investigators Earshot; and then using digital and aesthetic strategies to analyse the evidence spatially and chronologically.

What was atypical, however, was the speed of FA’s statement after the event. Usually, research is carried out, tested and analysed deeply before a public statement or report is published – often a long period after the violent act in question. In this instance, Piscitelli said, the urgency of the situation in Gaza required an immediate statement: “Sometimes, it is a political act to say we are here, we are watching.”

FA has undertaken a similar process of research into the repeated destruction of Palestine’s archaeological heritage. Living Archaeology in Gaza was published in February 2022 and took a deep dive into how archaeology in the Gaza Strip had been systemically attacked, from colonial rule through to the demolition of historic sites such as Anthedon in recent decades. Despite publication, no FA project truly ends, so when in December 2023 Al-Haq observed new evidence of the destruction of an archaeological site in proximity to Gaza’s Al-Shati refugee camp, the research was re-opened. “Through video evidence and satellite analysis,” Piscitelli explains, “we observed images of this specific area, and can start to see tactics – the Israeli army often air strike and then follow with a ground invasion.” It is both the depth and breadth of research evidence that offers a strong foundation to analyses by FA and Al-Haq.

The output of FA, whether online or in exhibition, is often compelling and visually arresting, although Weizman previously told me that “the idea of beauty is irrelevant to us – but the idea of aesthetics is extremely productive.” Within the context of an exhibition this approach can become complicated. There is no doubt that the models, mappings, videos and displays curated by Weizman’s team have an undeniable sublime beauty. Through their innate language of visual representation and a careful and strategic use of colour, the installations are alluring and striking. Yet, each project is rooted in the most inhumane and dark acts of violence against people, place and planet, which can work to provide a sense of profound shock to the viewer as they slowly read into any project, but has been accused by some as beautifying violence.

Piscitelli disagrees with that line. “There is no interest in making something beautiful – our aesthetic is more about sensing and making sense of the world,” he says, although there are an increasing number of institutions and governments seemingly unable to cope with the idea that politics can be deeply embedded within any artistic practice. In 2021, FA presented Cloud Studies at Manchester’s Whitworth gallery, an exhibition which evidenced research on ecocide in Indonesia, herbicidal warfare in Gaza and chemical attacks in Syria, amongst other bodies of research that included air pollution along the Mississippi River impacting black communities. Within the display was a statement of solidarity aligning the fight of the African-American community as “inseparable from other global struggles against racism, white supremacy, antisemitism and settler global violence”. This quote and descriptions of Israel in the exhibition led to a threat of legal action from UK Lawyers for Israel, with Whitworth director Alistair Hudson asked to leave his position.

Hudson moved to the ZKM | Centre for Art and Media Karlsruhe in Baden-Württemberg, perhaps expecting fewer political issues, although Germany is now a country where highly publicised political positions are making it difficult for artists and institutions to actively show Palestinian solidarity. Late last year, a talk at Aachen University about German police corruption by Phoebe Walton of the FA sister organisation, Berlin-based Forensis, was cancelled at short notice after Jewish and Israeli students told the university they considered the event “offensive” and highlighted Weizman’s support for the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions movement.

Israel and Palestine are, unsurprisingly, taking up much of FA’s resources and time, although its gaze falls wider, with many other Middle Eastern states also subject to its attention. Current projects include a digital recreation of Saydnaya Prison, meticulously developed through architectural and acoustic modelling derived from the testimony of detained and tortured Syrians; a series of reports on the Beirut port explosion, challenging official narratives through 3D models and unearthing the warehouse contents; and documenting the use of European weapons in Saudi-led coalition bombings of Yemen. In each instance, data, maps and carefully presented aesthetic and chronological evidence for each report are always open access and available for others to build on or critique.

The FA website lists nearly 100 such investigations from across the world, each diligently logged and artfully presented. This is only set to rise, with no suggestion of any imminent reduction in systemic and organised violence against states, individuals or the environment. As well as the ongoing research, there are also reports that are not yet published. “Most of the time it is about waiting,” Piscitelli tells me. “Maybe we can’t publish now, but we can publish it next month, or we will decide to wait because we want to make sure that what we’re saying is correct. We don’t rush, that’s fundamental.” But truths will out, and wherever the violence is enacted, Weizman, Piscitelli and the wider FA team and collaborators are there, and they are watching.