The Bahraini artist’s work lingers between the conscious and subconscious, telling autobiographical stories through ancient spiritual context while remaining in tune with Earth.

Canvas: Let’s start with your solo exhibition earlier this year in London, Angels in Purgatory at Vitrine Gallery. Where did this name come from?

Zayn Qahtani: I read a story about the Nephilim, who were a race of fallen angels. It was such a succinct story to use as a metaphor for the descent into the subconscious or the shadow self, because these characters give access into this twisted, unruly and rather dark world. The exhibition was about this back and forth between the self and the anti-self, or the conscious mind and the subconscious mind.

What are the sources of the rituals and religious or spiritual connections that run through your work?

Most of my work comes from the context of polytheistic religion, and more recently, borrowing from Abrahamic religions such as Christianity or Islam. I try to place emphasis on the matriarchal societies that existed in the ancient Middle East, or even more specifically Dilmun, the old name for Bahrain. My work is personal, but it’s expressed using the context of these ancient religions, and sometimes they will have borrowed titles or characters – goddesses or figures that I’m inspired by, such as Inanna or Ishtar. The works in the recent group show, Dreamers Eye in Edinburgh at Arusha Gallery, also tell autobiographical stories using some of this spiritual historical context. They are inspired by dreams, not as a phenomenon but as a human experience. I think of these dreams as a very separate place that we go to when we’re sleeping and perhaps don’t know how to necessarily anchor it back into our physical reality.

Photography by Jonathan Basset. Image courtesy of the artist and Hunna Art

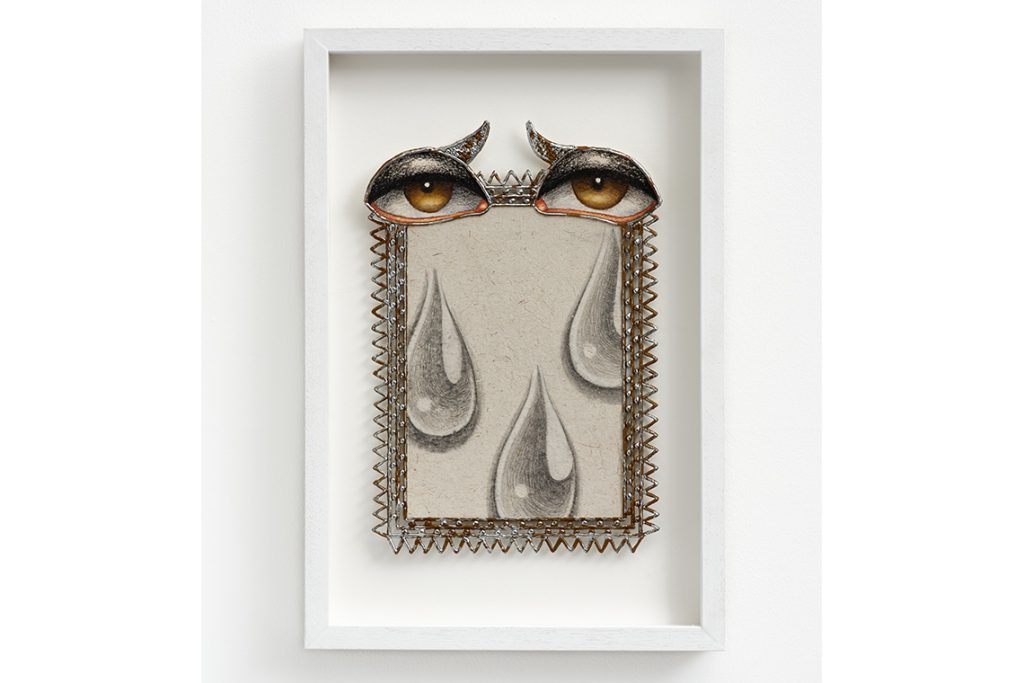

I also recently participated in a show in Greece, with Hekate Studios’ KIRKI projects, a nomadic gallery around the smaller islands. The group exhibition centred on tamata or votive offerings, so I started thinking about the funerary steles in ancient Sumeria and other parts of Arabia. They used to carve the faces of the deceased onto these tombstones, but this was also when there was a shift between the patriarchal nature of society towards a more matriarchal arrangement, and many goddess icons have been found. There’s a famous one thought to be Allat or Al-Uzza, found in the Temple of the Winged Lions in Petra in Jordan, but there are also parallels with Aphrodite in Greek mythology. For this work, I wanted to bring back this notion of offerings by remembering histories that are less spoken about, especially as these usually tend to be very male-centric.

You use natural materials and give new life to recycled objects. What role do these play in your work?

Materials are very important and a lot of the context to my work is hidden or woven into the materials I use. Paper is a good example. There’s an elderly lady in Bahrain who is one of the last people on the island to make paper by hand from date palm leaves. I found out that she had her own workshop preserving this craft, which I didn’t even know existed. There’s something that feels so correct, collaborating with the land that I’m speaking about through the materiality of the works, and that paper is very important to me because I try to be as sustainable as possible in my practice. I look at it as if I am collaborating with Earth, instead of just using the planet.

Also, when I’m working with colours, I’ll use pigments from crystals to represent certain symbolism. For example, in Angels in Purgatory, when talking about the self and the anti-self, the self was depicted in lapis lazuli, often a symbol of purity and historically reserved for the Virgin Mary’s robes. I liked turning that idea on its head and painting these fully fleshed-out bodies in a way that allowed them to experience that sense of purity and innocence without being sexualized. For the anti-self, which is painted with amethyst pigment, the stone is traditionally a scrying stone or witch’s stone, used to delve into the shadow self or subconscious part of your mind.

I also use a lot of found materials, maybe charms or little objects that I find in antique or thrift shops in my local neighbourhood. Then there’s also the bioplastics – people think that it’s metalwork when in fact it’s a trompe-l’œil. This plant material, usually derived from sugar cane or cornstarch, can be made to look like metal.

Photography by Jonathan Basset. Images courtesy of the artist and Hunna Art

Do you make your own pigments?

There was a time, perhaps two and a half years ago, when I was more into the drawing aspect of my work and colour was a lot more important. Back then, I was living in a little town an hour and a half away from London. It was in a very leafy area with lots forestry, lakes and rivers – an Alice in Wonderland-type experience, especially after growing up in the Middle East, where our idea of nature is different. It’s a much more barren context, one that has a lot to do with filling space, whereas in England everything was so dense and instead it became about navigating space. That environment was so rich with pieces of stone and brick that had fallen off old houses, all of which could be turned into pigments. Whenever you see a lighter pigment, maybe a white or a red, those are the ones I’ve made myself. There are also a few works about Sirens, such as Through The Looking Glass or Drown Into You (both 2022) , where the lapis was actually handmade. My mother is an energy healer and she had a bunch of broken lapis lazuli stones so I attempted to make my own pigment from them. It worked, but it was a long process.

You recently finished An Effort Residency. What’s next for you?

The residency wrapped up a month ago, but we still have a show coming up as an accumulation of the work and research. Early next year I have a solo show in London at Cromwell Place with Hunna Art and An Effort. It’s going to be a very death-centric show looking at Sumerian death rituals. It feels like a natural evolution from my first solo, which was about mental death or the death of the ego, but this one coming up is about death as a larger metaphor, not as an ending but as a new beginning.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 109: Smoke and Mirrors