The panoramic exhibition MANZAR: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today, organised by Doha’s future Art Mill Museum and presented in collaboration with the National Museum of Qatar chronicles the creative evolution of a young nation shaped by upheaval, entanglements and shifting identities.

How might one begin to grasp the creative evolution of an entire nation, from the moments leading up to its independence through to the present day? A country with such a rich history shaped by centuries of rule by numerous empires, distant modern movements and the intercultural entanglements of the Subcontinent’s many communities. A current attempt to unwind this complex web is the ambitious undertaking by Doha’s upcoming Art Mill Museum, scheduled to open in 2030.

The exhibition MANZAR: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today presents an unprecedented survey of Pakistani art and architectural history. Throughout, the show amplifies voices that are local and diasporic, historic and contemporary, emerging and renowned. “We began with a focus in the broadest sense, not limited to artists living and working within the country but extending to the porosities of Pakistan’s global ties,” explains the Art Mill Museum’s Senior Curator, Caroline Hancock, for whom the show is the culmination of years of cross-regional research between herself and Aurélien Lemonier (Architecture, Design and Gardens Curator), alongside Pakistani independent curator Zarmeene Shah and others.

Twelve thematic galleries navigate through the National Museum of Qatar and spill into its palatial courtyard, gathering more than 200 works that chronologically narrate around 80 years of history. Via multimedia artworks, architectural pavilions and archival documents, the curation confidently situates the country’s creative output within a global narrative while also celebrating its regional identity.

Art Mill Museum, Qatar Museums, Doha. Image courtesy of Grosvenor Gallery, London

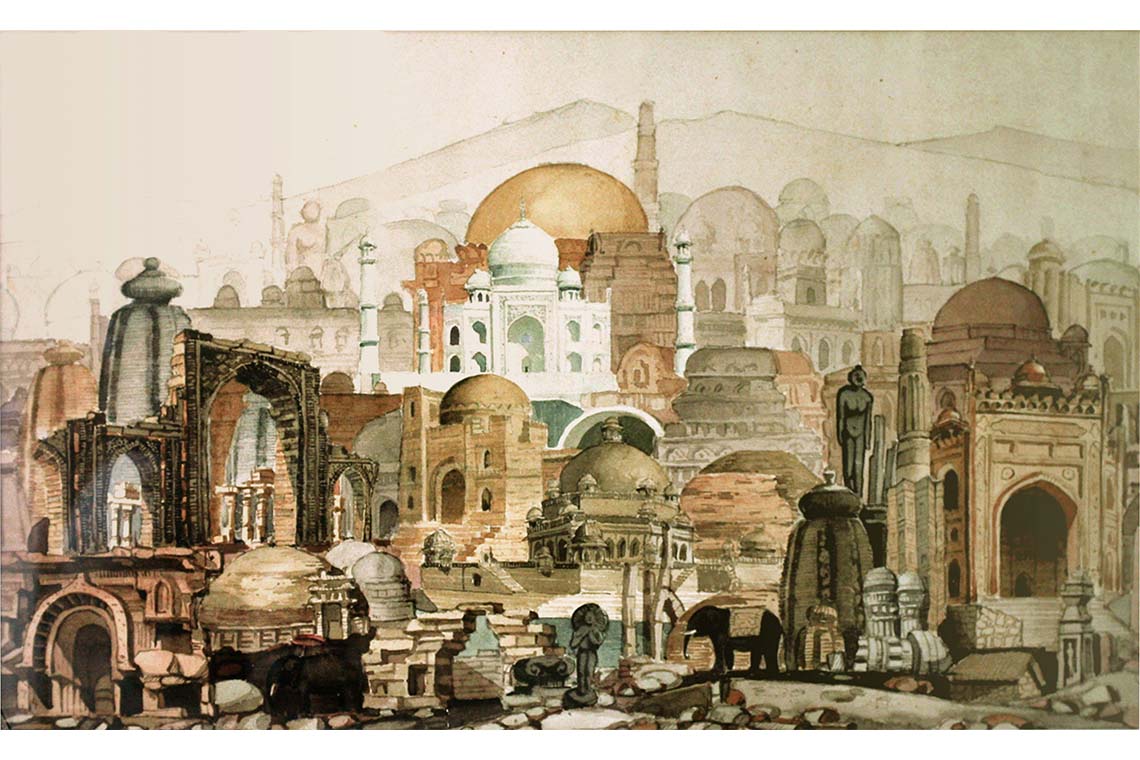

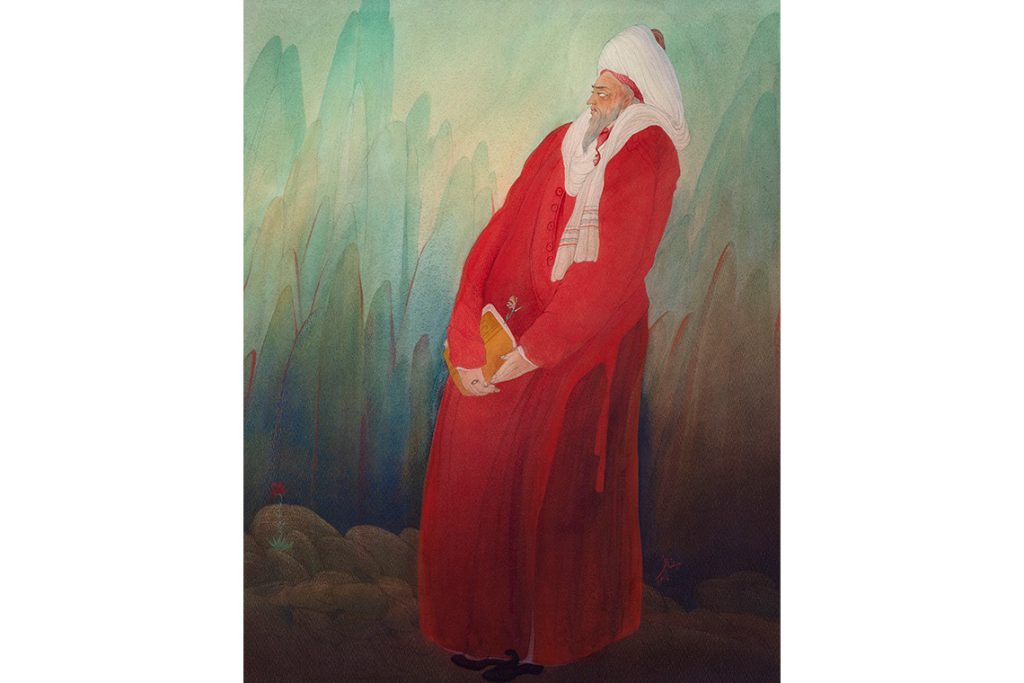

Pre-Partition masters, such as Ustad Allah Bakhsh and Abdur Rahman Chughtai, set the scene by chronicling the relationship between the land, its people and rural traditions. In Sohni Mahiwal (1923), Allah Bakhsh illustrates a centuries-old folktale of love set in a Punjabi village, while Chughtai’s miniatures capture feminine muses in strokes evocative of both Orientalist and Islamic styles of painting. Their paintings and etchings are echoed by Bangladeshi artist Zainul Abedin, whose famine drawings from the 1940s recount colonial-era traumas with a raw social sensitivity. Amid sentiments of social upheaval, these cross-cultural dialogues then draw attention to the “alliances and friendships across what now seem like impermeable borders”, as co-curator Zarmeene Shah puts it.

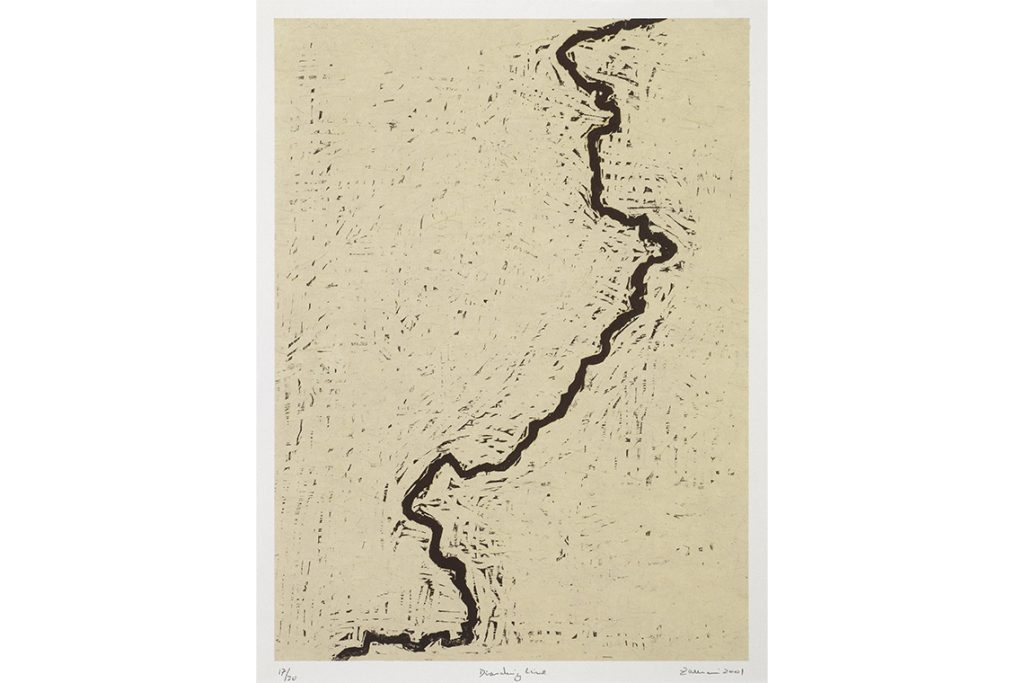

Acknowledging the Subcontinent’s division into these independent nation states as integral to Pakistan’s conception, migration becomes core to its identity. The idea of traumatic beginnings reverberates through works by artists including Zarina, Anna Molka Ahmed and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Zarina’s Letters from Home (2004) captures her longing for a house to which she could never return, artfully expressed through the superimposition of a woodblock-printed floor plan atop letters from her sister. Meanwhile, Ahmed’s 1970s oil paintings starkly depict the violence and bloodshed that marked this division of land, rendering the scars of Partition with unflinching intensity.

Image courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York

MANZAR further presents a stage for many artists born into post-colonial Pakistan. For these generations, the quest for new forms of regional identification is intertwined with a new phase of globalisation. The nation’s modernists, such as Shakir Ali and Zubeida Agha, travelled and practiced abroad and began to forge vocabularies of their own. Their explorations of colour, geometry and theme are notably influenced by European Cubism and Abstract Expressionism, yet distinctly rooted in local sensibilities. When situating modernism in the South Asian postcolonial discourse, artist and poet Sadequain is at the forefront – credited as the father of a new calligraphic style that converges Islamic motifs with post-Cubist frameworks.

Many diasporic contemporary practitioners are also currently expanding these visual and conceptual dialogues on global stages. From Naiza Khan in London to Khadim Ali in Sydney, these creatives at MANZAR emphasise the transnational layer of the Pakistani art scene while interrogating ideas of state, identity and displacement.

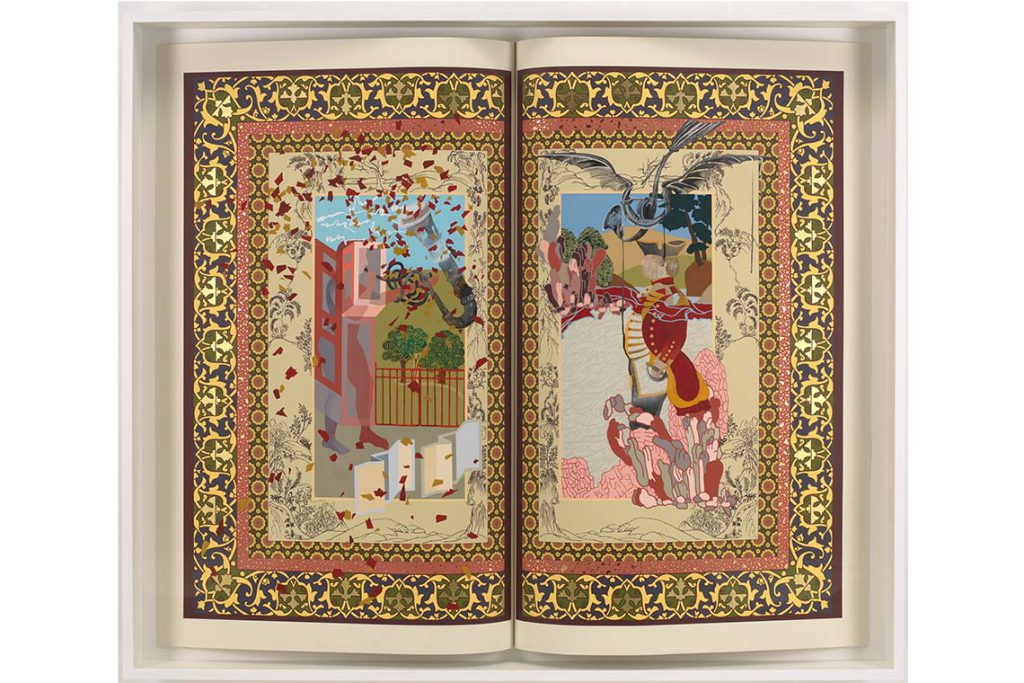

Important among them is Shahzia Sikander, who occupies a prominent presence in shaping the neo-miniature movement born in Lahore in the 1990s and which revisits an historic painting tradition through a modern lens. Through works grappling with socio-political and personal concerns, such as The Explosion of the Company Man (2011), the US-based artist is one of the first to engage with an art form that can be traced back to the Indo-Persian empires. Carrying this language forth in abstraction are Rashid Rana’s first photomosaics, which critique urban consumerism by interpolating Lahore’s commercial billboards into Mughal miniature portraits. This series also finds one foot in the Karachi Pop movement of the 90s – a Pakistani parallel to Western Pop art. Here, Iftikhar and Elizabeth Dadi, David Alesworth and Durriya Kazi began looking at cinematic perspectives of regional crafts, street life and folk culture.

Taimur Hassan Collection. Image courtesy of the artist

Urbanism, too, is inherently carved from and indicative of any new nation’s aspirations. MANZAR’s architectural segment offers another layer to explore Pakistan’s intersections between history, politics and ecologies. The early post-Independence years saw collaborations with international architects such as Louis Kahn and Constantinos Doxiadis, who created the masterplan for the new capital city of Islamabad. These projects are contextualised in the exhibition against plans and elevations by Pakistani architects who later redefined regional modernism, including Habib Fida Ali, Nayyar Ali Dada and Kamil Khan Mumtaz. The only woman among them is Yasmeen Lari, whose bamboo shelters provide vernacular-inspired solutions to ecological concerns such as flooding.

While the exhibition’s subject is vast yet comprehensively tackled, it refrains from boxing Pakistan’s complex cultural conversations into conventional, Western-centric movements. It instead adopts an objective, linear approach. Its title derives from the Urdu, Arabic and Farsi word for scene, perspective or landscape. Here, intentionally employed in its singular form, manzar resonates with the curators’ intention to pose a fundamental way of seeing. By just “tracing trajectories”, as Zarmeene Shah writes, this becomes the prelude to understanding the complex multiplicity of stories that have emerged from the nation. “It also finds a fundamental connection with the aims of the exhibition: to showcase the diversity of social, political, historical and cultural influences and thought that have manifested through the works of artistic and cultural practitioners in the country,” she notes.

MANZAR: Art and Architecture from Pakistan 1940s to Today runs until 31 January