The artist speaks to Canvas about her use of textiles and written, audio and video accompaniments that bring to life artworks exploring identity, personal history and memory.

Canvas: The term al ghorba is often referenced in your work. What does it mean to you, and when did you first discover it?

Hana Almilli: Al ghorba is a very specific word in Arabic, meaning a sense of alienation combined with nostalgia for home. To say “I live in al ghorba” means to live in that state of alienation. I hadn’t thought of the word until I travelled abroad during my studies, when I was separated from my family and my world. I felt al ghorba because I’ve always been trying to discover what my identities are, since I grew up with a diverse cultural background. My mom is Saudi–Syrian, and grew up in Syria, and my dad is Kurdish–Turkish, born in Lebanon, but raised in Syria, so they also felt this way. It’s a generational ghorba. It can sound negative, although for me it is also a positive. It pushed me to rediscover my identities, my cultures, and everything that has to do with who I am. So I would thank this term, because it was my starting point. It got me to where I am today as an artist.

As part of this project you wrote a poetry book, also called Al Ghorba. When did poetry become part of how you express yourself?

I’ve been writing poetry for a long time. My mom’s a poet and a writer, and I used to go into her room and ask her to show me her poems or read one to me. At the time, I would write things and just hide them, because they spoke about how I felt but was not fully aware that I was expressing in a creative way. At college I had the opportunity to explore poetry further. Art school pushes you to test the boundaries of artistic expression and ever since then, I’ve written something with every single art piece. It’s almost as if it’s another representation of the artwork, because my pieces are always inspired by poems or moments of some sort.

When did you begin incorporating textile into your practice?

My grandma, who I was very close to, used to come to Saudi Arabia for six months almost every year when I was younger. She loved knitting, crocheting and anything to do with textiles. I remember going with her to one specific place every single summer, a textile store where you could buy yarns. I would just be engulfed in this world. This place is actually still open today, and I still go there. My grandma’s a big inspiration for how this all started. I was initially in the USA studying architecture, which I thought I had a passion for, along with design. Then one day I realised it wasn’t for me. I needed a better way of expressing myself. I knew I could push myself towards something more emotional, more creative, more expressive and more free. I took a knitting class during college, to remind myself of these nostalgic moments with my grandma. I quickly found out that textiles were a whole world and realised I could express myself even further and study this, so I changed my major. Since then, I’ve been learning how to jacquard weave, floor loom weave, naturally dye

silkscreen print, everything to master textiles as a material. Towards the end of college, I began thinking about the series of alienation, which is still ongoing. I don’t think I’ll ever be done!

Image courtesy of the artist

Yes. For the piece that you referenced, Mazaj, I used the T-shirt of a friend who had passed away, which I was given as a gift from their family. I had the honour of taking one of the shirts and recreating an image of them as a weaving, which is distorted as if they’re a lost memory. At the same time, it’s a commemoration of them. A lot of my pieces speak about death and loss, and dealing with that. I think working with textiles is a gateway into a meditative state, this repetitive motion, the thoughts, the processes. Especially with weaving and knitting. Every emotion you feel in the process is displayed within the work. For example, if you’re angry, it’s agitated from the sides. If you’re stressed, it’s uneven from the sides. There’s a very big connection with clothing because it holds memory, it holds a person’s scent and holds that person. This is very important and translates into my pieces.

How do you source your materials? In one work you use your friend’s T-shirt, in another some soil from Saudi Arabia. Are these all things that you have a personal connection to?

I always research materials that connect me further to my ancestors and my heritage. Recently, I’ve been trying to source most of them locally, like natural dyes from flowers, which my ancestors would have used to dye their clothes and other textile items. There’s always a pre-thought to the process, a connection. The best way for me to relate to these messages is usually to do everything myself, from A to Z. This could be naturally dyeing something, or gathering soil from a specific area to use in my work. There are always ways to reconnect my heritage to the pieces I make, which is very important for me and my practice.

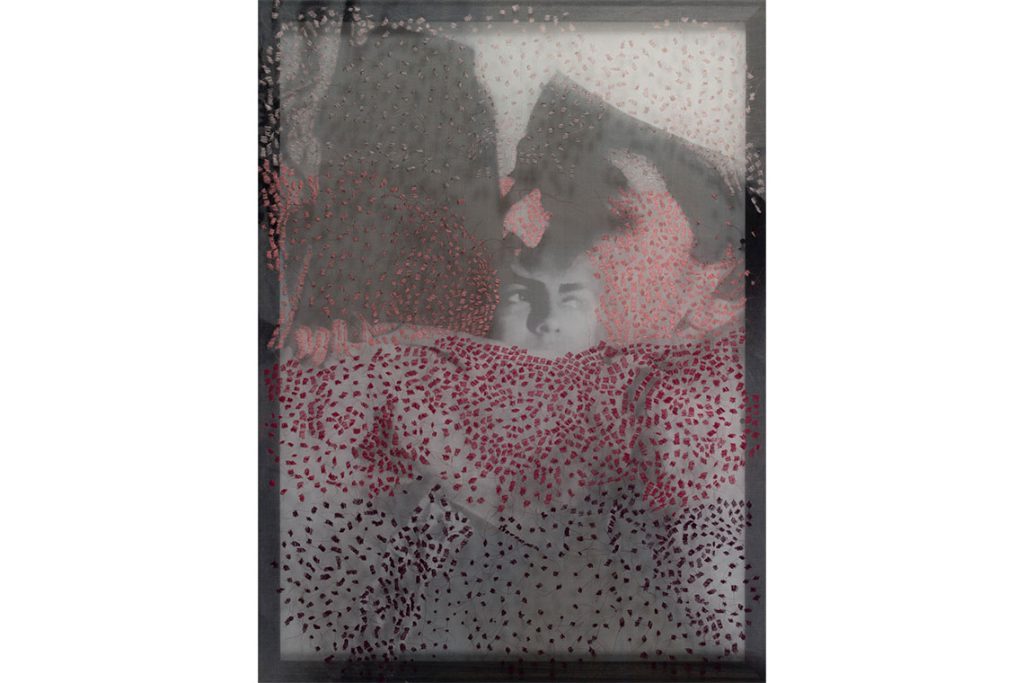

Hana Almilli. Languages Interlacing 02 – Echoes of my. 2019. Printed photographs on silk organza, embroidered with 100 % cotton, multiple colored threads. 110 x 87 cm. Image courtesy of the artist

Your work is about recreating and reconciling distinct identities. Is this a way for you to relive something through your ancestors and make sense of who you are?

It’s about the ability to reconnect. I was lucky enough to have all of my grandparents be a part of my life growing up. But I always think about the fact that when they’re gone, so too is a long history. As much as possible, I sit with my dad, my mom or my grandma, and ask questions. I wonder what their lives were like, what they experienced, what their memories were, how they felt living in a place they are not from. Last week, I sat down with my dad for a whole hour, and he told me about his childhood in Syria. I was amazed at how he remembered these little specific details, like having luggage and carrying it around at five or six years old to reach his grandma’s house and knock on the door. He remembers that she’d have to look down, because he was so small.

I think these stories are so important to live because they’re a part of who I am and of what I represent. I don’t want anything to be a forgotten history, whether my Kurdish, Turkish, Syrian or Saudi sides. It’s important to me that future generations understand all of these places. No matter how unfortunate the situations are right now, it’s important for me to connect with them. If I don’t, I lose them, I lose that history, I lose that identity, and I no longer know what I represent.

You spent some time in the West, especially in the USA. How did people there view you and your background?

Being in the USA was a very interesting time for me. I went to an art school where people were generally fascinated by what the world has to offer, and I’m thankful that I never felt misunderstood. They were actually intrigued and would want to learn. That was an advantage, since through my art I was able to show them how beautiful our area is and how much passion we have for our culture. I felt very lucky to be able to sit down with people and explain that to them.