The Kuwaiti-Ukranian artist and designer bridges creative spheres and cultures in a textile-based practice that uses tradition and socio-politics to develop deeper understanding and open new channels of thought.

Canvas: How did you first get into art?

Amani Al Thuwaini: Very organically. I was born and raised in Ukraine and my connection to that context, and exposure to its specific media, cartoons, fairy tales and crafts, influenced the way I see things and make work. My childhood drawings affected me deeply – I’ve kept around 200. I used to wake up before my siblings just to be able to draw and paint, to have this moment alone. I still crave this solitude and make time for it to think and create.

How has Ukraine’s relationship to art influenced you?

The focus was on, let’s say, Soviet fairy tales and illustrations. That specific style, for example, has women with long braids and Russian tiaras. There is an abundance of pattern, colours and ornamentation, with many references to different forms of textiles such as fashion, carpets and tapestries. At the time, it was also common to see carpets hanging on walls. That was my first encounter with textiles. There is also a huge emphasis on the contrast between luxury or excess versus the mundane. Lots of very old fairy tales and books influenced me as well, and more specifically, the way women are depicted is very unique.

Carpets are often associated with the wider Middle East, are they a cultural common ground between Kuwait and Ukraine?

I do focus on the connection between the East and West in my work and the influence of specific cultures on one another. I also feel that, emotionally, carpets provoke a kind of a feeling of ‘home’ or belonging – memories of wall-hung carpets at home have always stayed with me. I’ve had this question of belonging, because I’ve always felt as though I’m in-between.

Do you think you would have the same affinity for textiles if you had not experienced two different cultures growing up?

I don’t think so – when I came back to Kuwait I felt that flash, that huge difference, which in turn emphasised those memories and feelings towards specific materials.

Your work also oscillates between the traditional, Islamic and contemporary. How do you find a balance?

What I create – the forms, materials, surfaces and symbolism – are mainly things that I’m curious about and feel foreign to me. It’s always based on this curiosity and a kind of alienation, let’s say. I want to ‘grab’ or ‘catch’ what I’m unfamiliar with and find out more. The art-making process is a form of research, figuring it out, making sense of it all. That is how I began to focus on dowry culture and traditions. I felt like an outsider and it was really strange, even when I received my own dowry, for example.

Where is the line between observing, asking questions and critiquing or commenting on a subject?

My work is a combination. It’s asking questions, but it’s also celebrating something. It is an attempt to mark a specific moment, story and tradition at a specific time that I feel needs to be documented. The critique is very subtle. Although people may think that I am against something, that is not necessarily the case. I may be against the way it has transformed, due to globalisation, or excess within traditions, for example. I’m going back to the essence and root of the beautiful idea of a tradition, but critiquing the way it is now celebrated or displayed.

Your works are presented in contemporary contexts – galleries like Hunna Art or events such as Paris Art Fair – but incorporate materials and formats with long histories of craftsmanship. How hands-on are you with production?

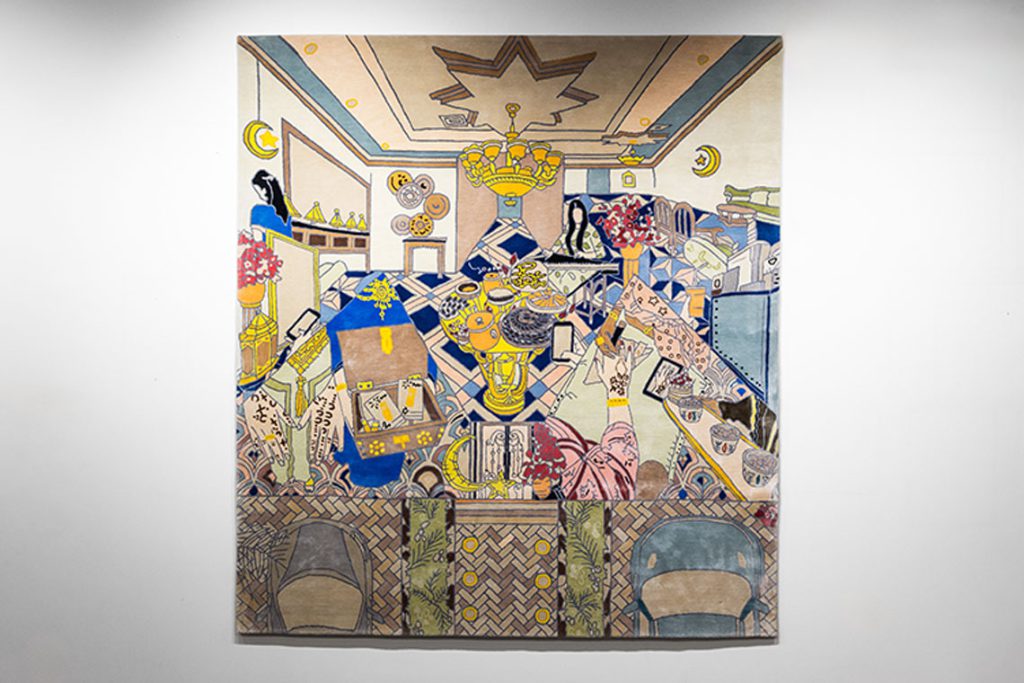

I have made a few works using Hoffman, German machines and tools which I was introduced to when I was doing my MFA at Goldsmiths in London. They’re very professional, heavy-duty and allow you to make cut pile or loop pile carpets. I use mainly cut pile and I’ve made a few by hand. The latest work, Ghabga (2024), a silk hand-tufted cut-pile carpet referencing the period between iftar and suhoor when people express their generosity and build social connections, was a one-off collaboration with Samovar Carpets and was produced by them in Germany. But making my own with my own tools is something I really enjoy.

Which pieces have you made yourself?

The process of creation is amazing. Elibelinde (2017), a stretched tufted carpet with laser-cut plexiglass and digital embroidery, features a blown-up motif from a Turkish kilim. It represents fertility and womanhood, and the five feet represent women’s agency. I used that to represent one of the dowry traditions and juxtaposed it with some elements from Kuwaiti dowry tradition, such as buqsha. This is an embroidered bundle of select fabrics, a common form of dowry, which the groom’s family walks to the bride’s house through the alleyways between Kuwaiti mud-brick houses. Behind the buqsha is a Cinderella-like carriage made of gold plexiglass, which references fairytales.

You have a background in design, with an architecture degree from Kuwait University. Does this have an impact on how you translate your ideas onto your materials? Do you find that there are any limitations to working with textiles when you go from concept to execution?

I always design on AutoCAD, which I am very familiar with. The most exciting, and most challenging, part of the process is the planning. It lets me play with scale, mirroring, moving, reflecting, adding or juxtaposing elements on top of each other to create something different from the original image. That’s when the ideas start forming. After AutoCAD, I translate the design into colour and details. I go back-and-forth between hand sketches and computer sketches, but the initial form is created digitally. The details are spontaneous, however, because I always try to incorporate some spontaneity or freedom, let’s say. It generates this tension between carefully planning the artwork and adding unexpected elements from the soul. There are limitations, though. I cannot have something very tiny due to the restrictions of carpet making. That is why I have this desire to create work that bridges the gap with painting. It pushes the limitations of carpet making.

Can you walk us through the process of working with other kinds of textiles, such as for Manifestation of the Dowry (2018), which incorporates leather, vinyl and embroidery?

That was also an attempt to push through the limitations of the material. I used a digital embroidery machine to write Arabic words that represent specific meanings, for example, presenting a play between mahar-math’har (‘dowry’). Adding one letter shifts the meaning of the word and it becomes ‘display’ or ‘appearance’. It was also an attempt to add unexpectedness and mystery. The image on the vinyl is one that I took of myself wearing fabric like a garment. I wanted to find an alternative to painting with the work of textiles. Together with the leather frame, it represents a wedding chest.

If the artworks are guided by questions, at the end of the process, from a design and production standpoint, as well as conceptually, do you find that you have a better understanding or answers?

With a series, I get to a point of satisfaction. Not necessarily answering all the questions, but the whole point is to trigger discussion, bring more people into the conversation. An example of how one thing leads to another – and is not necessarily about answering the question – is a piece I’m working on right now on the topic of motherhood. I am in the process of creating and designing the forms and, through my questioning, I researched biology, which opened up more exciting things to look at and think about, in turn leading to me to a biochemistry lab! I would not have expected myself to be there.

The symbolic, expressive values of your oeuvre contrast with your meticulous design methodologies and touch equally on both the design and art disciplines. Is there a difference between the two for you?

Design can be something that is not necessarily asking questions or criticising, or conveying a specific message. Art does the opposite. It conveys a feeling, a meaning. I’m always in-between, because I want something to be visually striking and act as a symbol that references something. The stories that I put into my artworks add depth, thought and emotion. They ask questions.