More questions are raised than answered in Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme at Mathaf, a three-part exhibition which seeks to reassess the work and impact of one of the foremost Orientalist artists.

The future Lusail Museum in Doha, due to open in 2026 with the largest collection of Orientalist paintings in the world, states on its webpage that its aim is to question how this art can be presented today in a museum in the Arab world. It particularly asks: “What can we learn about 19th-century power structures and the construction of Arab identity from these paintings, and how do they continue to influence perceptions?”

The museum’s first exhibition, organised in collaboration with Mathaf, gives some puzzling answers as it seeks to navigate how best to present the work of Jean-Léon Gérôme in the current post-Orientalist context. What has changed, and are we ready to look at Orientalism differently, particularly when an exhibition like Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme, which celebrates the 200th anniversary of the artist’s birth, takes place in the Middle East? Furthermore, what can Orientalism in art teach us about representation in the region today, and are we ready to de-politicise the works of an artist like Gérôme in favour of a deeper dive into his methodology?

Despite the discomfort associated by some with Orientalism, the first part of the exhibition, focused on Gérôme’s paintings and his inspiration, still elicits murmurs of awe and wonder for the work’s undeniable beauty. Emily Weeks, curator of this section, invites us to take a new approach to this leading Orientalist’s paintings. She places him in the context of his time, looking at how he compares to his contemporaries, rather than viewing his work from a political standpoint inspired by the critique of Orientalism made by Edward Said, whose seminal 1978 work is displayed in a glass case in the exhibition. Gerome’s Snake Charmer (c. 1879) takes the cover of this early edition, effectively making the French painter the poster boy for Orientalism in all forms, even if Said never explicitly referred to Orientalist art. Although Gérôme was a Westerner depicting what today would still be considered a type of fantasy view of the Orient, he travelled repeatedly and extensively in the region and, superficially at least, the scenes he portrays come across as believable snapshots of everyday life in the nineteenth-century Middle East.

Gérôme is certainly worthy of attention for his technical accuracy. As well as field sketches, he also worked from photographs taken during his travels and was dedicated to the perfecting of details in his compositions. His ability to capture light stands out particularly in his desert scenes; he reportedly stayed out for days to chronicle the shifts in light on the sand. A more critical eye can always be taken in terms of how people are depicted in Orientalist works, and here again Gérôme merits a closer look. Take his Harem in the Kiosk (1870–75), in which a group of women congregate outdoors, in the background of the painting, while a guard – his back turned to the women – faces the viewer. This work displays a markedly different approach to the harem than that adopted by many other Orientalists (and indeed from that taken by Gérôme in some of his other works), in which fanciful scenes of these female-only spaces serve more as a testament to male sexual fantasy than any kind of accurate depiction of this social institution of the time. Here, the women are covered, any sensuality deriving from what cannot be seen rather than overtly suggested.

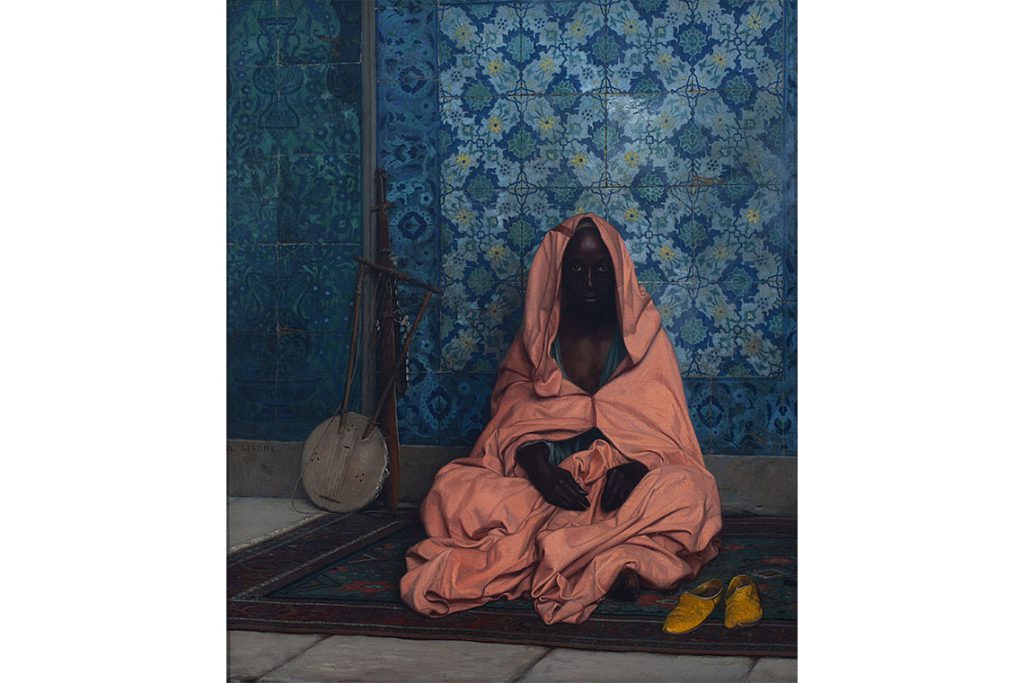

Harem in the Kiosk notwithstanding, it is difficult to ignore the power dynamics of a Westerner representing ‘locals’. Gérôme’s The Black Bard (c. 1888), one his most magnetic works, sees a cross-legged cloaked man staring intently out from the canvas. We are easily drawn into believing that the subject of the painting was painted from life on the streets of a Middle Eastern town. Yet the reality is rather different and more complex, with Gérôme’s finished bard a layered amalgamation of field observation, sketches and work with a professional model and artefacts in his Paris studio – demonstrating how the lines between fantasy representation and reality become disconcertingly blurred in the hands of an artist as skilled as Gérôme.

The following section, independently curated by Giles Hudson, senior curator of photography at the Lusail Museum, does little to assuage this feeling. While an examination of how Gérôme influenced later photography in and of the region might have some traction (especially when it comes to the use of “Oriental light”), an undue emphasis seems to be placed on technique without further scrutiny of the implications on representation more widely. The inclusion of the famous National Geographic photograph of the “Afghan Girl” from 1984, which we are told is there to showcase how Gérôme’s “light” endures, is jarring and profoundly uncomfortable, as it glosses over the questionable methods used to obtain the picture in the first place. The unwavering and angry stare, which made for such a strong photograph, is arguably a result of the very approach for which the Orientalists have been criticised: encroaching on what were usually considered private spaces, taking liberties with representations of locals with minimal consent and reducing them to objects for consumption by Western audiences. Not acknowledging this dimension feels like falling short of the Lusail Museum’s aims.

Such issues are finally addressed in the final section of contemporary Arab artwork, curated by Sara Raza. In what feels like stepping into an entirely different exhibition, we are invited to ponder further representations of the Middle East, but this time by Middle Easterners. The variety of artworks quickly demolishes the monolithic representation of the Middle East found in Orientalism. From Baya Mahieddine’s colourful naïve paintings to Ergin Çavuşoğlu’s Quintet Without Borders (2007), in which Roma virtuoso musicians from a border town in northwest Turkey play music inspired by their history and traditions, which include Turkish, Greek, Roma, Jewish, Bulgarian, Armenian and Arabic roots, notions of historical Western representations of the Orient, including Gérôme’s depictions, are utterly destabilised. Orientalism in art, in contrast with Raza’s lively display of work, suddenly seems rather reductive.

This aspect is addressed by Raza, who sees Orientalism as part of a continuing cycle of stereotyped images slowly infiltrating the news, Western collective consciousness and contributing to the ongoing ‘othering’ of the Middle East. Lida Abdul’s Dome (2005), a short video in which a child dances like a whirling dervish inside what is presumed to be a bombed-out mosque on the outskirts of Kabul as an American warplane flies overhead, is a stark reminder of these consequences.

How, then, can contemporary artists, and by extension their audiences, engage with Orientalist art? Perhaps visually reappropriating its subject matter is one of the potential answers. Inci Eviner’s Harem (2009), juxtaposed with a nineteenth-century engraving made by Antoine Ignace Melling of a precisely rendered interior of a harem in which the women are engaged in seemingly routine tasks, brings to life the languid, fantasy figures of the Orientalist depiction. Scheduled to be part of the show, it was present for the press preview but subsequently withdrawn ahead of the public opening, without warning and explanation, in what the artist described as an act of censorship. Whatever the reason, the work’s removal underscores the problems facing Middle Eastern artists as they seek to reclaim aspects of clichéd and misleading representations of their region (in this case, of women and their bodies) and tackle issues which, however timely and relevant, remain challenging.

Raza ultimately leaves us pondering how contemporary Middle-Eastern artists are seeking to reassert the complexity of their identities in contrast to the simplified Orientalist representations of the past. One of few commissioned works for the exhibitionis Nadia Kaabi-Linke’s One Olive Garden Tree (2024), a collection of olive tree trunks encased in concrete and arranged like a labyrinth, apparently to echo the “notion of the Orient as a puzzle that must be solved”. Whether such a conundrum still has any direct validity is debatable. Even if the mystery of the “Orient”, as seen in the work of Gérôme, continues to have traction in the West’s collective imagination, it is surely overpowered by more dynamic and immediate images of violence, war and turmoil in the region.

Middle Easterners still do not have agency in terms of how the West chooses to portray them, but they can control whether or not they accept being reduced to this narrowed identity. As the region’s contemporary artists choose to challenge past and present depictions, physically bringing the world’s largest collection of Orientalist artwork to a museum in the region is surely a worthwhile step in helping to reappropriate the art of representation for local audiences. Exactly how the Lusail Museum will achieve this ambitious and complex objective going forward remains to be seen.

Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme runs until 22 February