The second edition of the Islamic Arts Biennale takes place in Jeddah and offers deep layers of history and heritage with a lighter twist of the contemporary.

Under the iconic tented canopies of the Western Hajj Terminal in Jeddah, the Islamic Arts Biennale opened its second edition in January and is set for a four month run. It takes as its title part of a phrase that recurs many times in the Qur’an, which holds that God created the heavens, the earth and everything between the two: And All That is in Between, supported by the explanatory Exploring Faith Through Feeling, Thinking, and Making. It is the latest in a steady march of “between”-themed shows in the region, with recent examples including Noor Riyadh 2024’s Arabic title Between the earth and the sky and NYUAD’s Between the Tides: A Gulf Quinquennial. This biennale is curated by scholars Abdulrahman Azzam, Julian Raby, Amin Jaffer and artist Muhannad Shono, with the latter handling the contemporary works. With loans from more than 30 major institutions and featuring some 500 artefacts and objects, it is both much more ambitious and more historically focused than its predecessor, if rather less immediately exciting.

Eschewing any top-level narrative flow, the biennale functions as an umbrella housing seven thematic presentations across five halls and two outdoor spaces. The first section, Al Bidaya (The Beginning), unfolds across three subsections and explores faith, moving from humble piety to transcendence. To be clear, the quality and breadth of objects on view is nothing short of astonishing, and in this sparely hung section with whispery, almost ethereal scenography from OMA, they are given ample room to breathe.

Photography by Marco Cappelletti. Image courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Many of the pieces come directly from Islam’s two holiest mosques, and tell a story of royal patronage and pious gifting, as well as of the historical renovations and expansions of these sites. They include a stunning carved teak staircase or madraj donated by a Carnatic Nawab, once used to enter the Kaaba, and a monumental Mughal-era Qur’an. A number of pieces come directly from the House of God itself, such as the key to the Kaaba, the golden, spiky Kaaba waterspout known as the Spout of Mercy (for everyone except for pigeons, given its formidable anti-perching system) and the silver casing of the Black Stone from King Fahd’s time, in addition to the Abbasid-era columns that stood in the Masjid Al Haram’s courtyard until 2011.

Particularly notable is last year’s Kiswah, or Kaaba covering, which is usually replaced annually, with the old one cut up for diplomatic or pious gifts. This year, however, the Saudi authorities decided to keep it intact for display at the Biennale, where it can be seen outside of Makkah and by non-Muslim eyes for the first time, in celebration of the centenary of the Kiswah being manufactured in Makkah. Taken together, all these objects provoke interesting questions about the nature of sanctity in the Haramain and whether it is these objects, imbued with auratic spiritual presence by association, even when decommissioned, or the ground itself that is sacred and off-limits.

If the inaugural iteration of the biennale included historical artefacts to offset the contemporary works in its main exhibition, this edition inverts that approach, with occasional new commissions serving to complement the heritage objects. At the risk of unfairness, given how remarkable the first, Sumayya Vally-curated edition was, it becomes hard not to compare the two. While the inaugural biennale included mostly Muslim artists to consider the rituals, practices, sociopolitics and lived experience of both Islam and Jeddah as the gateway to Makkah, this edition casts a wider net, with mixed results. There is a shifting of scale away from the personal to focus on power, patronage and geographic plurality in Islamic civilisations, through the magnificent objects that they have produced.

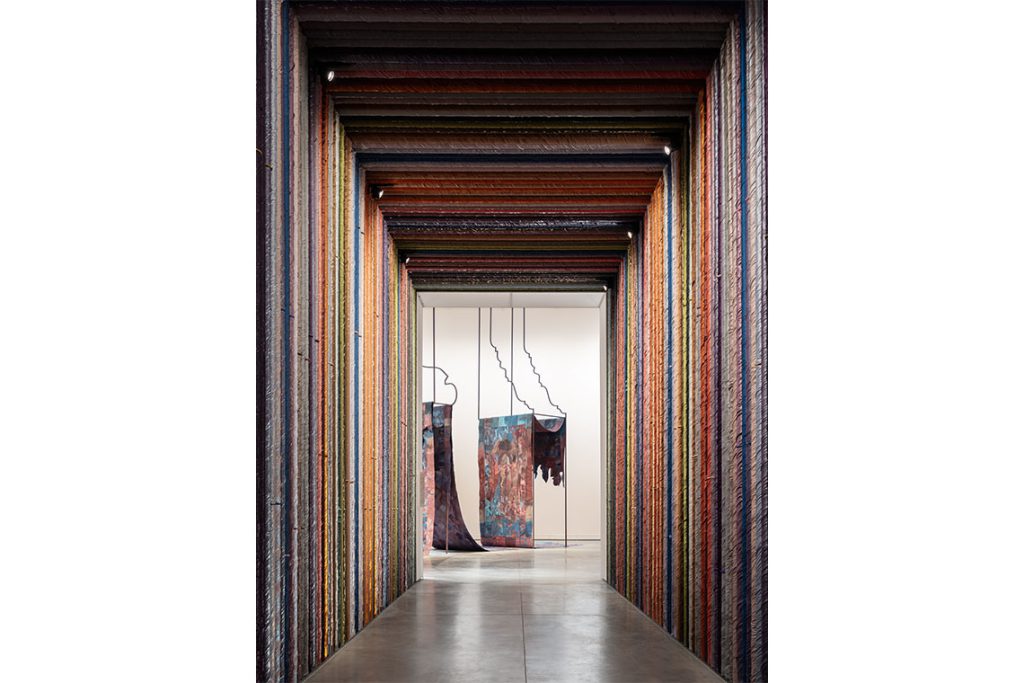

In Al Bidaya, special commissions (all 2025) include Nour Jaouda’s textile installation Before the Last Sky (see page 80), a suspended triptych inspired by portable prayer mats that create a temporary sacralised space. Largely absent in this biennale, the body is intimated here in the hand-dyed panels, which are oriented, like worshippers, towards Makkah, and are each draped in a manner that resembles the bowing, kneeling and prostration of salat. Hayat Osamah’s Soft Gates racks rolls of fabric along a passageway between galleries in a testament to her close-knit Riyadh neighbourhood, while Arcangelo Sassolino’s Memory of Becoming, a slowly rotating disc dripping in industrial oil, is interesting in its petromateriality even as it fuzzily gestures towards time, metamorphosis and ontology. Especially rewarding here is Asif Khan’s Glass Qur’an/Mushaf al-Zujaj, which hand-gilds the text of the entire Qur’an onto 604 stacked folios to create an elegant work that suggests nothing so much as kadayif suspended in a glass brick.

Installation view of the AlBidayah component, Islamic Arts Biennale, 2025. Photography by Marco Cappelletti. Image courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation

Particularly successful this edition are the returning Al Mukammarah (Makkah) and Al Munawwarah (Madinah) pavilions. Crowded museological affairs the first time around, they are judiciously hung and effectively invoke each holy city’s spiritual energy, whether intensely magnetic or peaceful. Highlights in these permanent pavilions, which will remain open after the biennale closes, include mammoth tombak, or gilt copper, candlesticks and a crescent finial from the Prophet’s Mosque, and an eleventh-century brass map from Iran, which shows 149 global cities in relation to Makkah at its centre. Other sections include Al Madar (The Orbit), which focuses on numbers in the Islamic world and is filled with cartography, astronomical and timekeeping devices, and Al Muqtani (Homage), which pays tribute to two major collectors of Islamic arts and is a veritable treasure trove of material and chivalric culture, including a bejewelled Mughal parrot and engraved early Ottoman chamfrons, or plate armour, for horse heads.

Outside, the biennale includes the winner of the inaugural AlMusalla Prize, an architectural competition to design a sustainable prayer space which mandates a collaboration between architects, engineers and artists. The modular structure On Weaving (2025), from EAST Architecture Studio in collaboration with AKT II and Rayanne Tabet, is as gorgeous as it is unwelcoming. It repurposes date palm waste in the form of woven fronds and wood composites for an outcome that reads fascinatingly as Khaleeji Heritage Luxe – the material innovation equivalent of someone placing an Aesop soap in their guest bathroom, and angling it just so.

Photography by Marco Cappelletti. Image courtesy of the Diriyah Biennale Foundation

A final outdoor section, Al Mathala (Canopy), features most of the biennale’s new commissions (all 2025), somewhat vaguely themed around an Islamic garden. It has its standouts too, chiefly Anhar Salem’s Media Fountain, a water fountain tiled with tiny mosaics drawn from Islamic digital culture, with a sonic component activated when someone places their hands under the spout – most visitors adopt an open palmed dua– or wudu-type gesture. Also compelling here are several works which pay a tribute of sorts: Ala Younis’s greenhoused paean to the dying Gazan cut flower industry, Bilal Allaf’s video documenting a 24-hour endurance performance based on Hajar’s gruelling search for water, and Fatma Abdulhadi’s cathartic walkway I wish you in heaven, whose kinetic screen-printed panels are programmed to move just enough to bruise the basil bushes planted below, releasing a sweetly elegiac scent. And entering Tamara Kalo’s copper, fire ant-like camera obscura provides a view of the Hajj terminal as a whole: the canopies, the earth below and everything in between. Elsewhere, in a transitional space between sections, Lucia Koch’s Air Temperature features more translucent panels that are especially pleasing in their Chips Oman gradient.

Mostly, contemporary art feels very much like an afterthought in this biennale, which is not necessarily a bad thing given the rigour of its historical sections. If the first edition radically expanded the field of what an Islamic arts biennale could look like, could feel like, this sophomore effort brings it very much back to business as usual. As a whole, it feels like a teaser for a forthcoming, high-quality museum dedicated to the Islamic arts. Yet one is left wondering what will happen in future editions, if what can be loaned has already been shown?

The Islamic Arts Biennale 2025 runs until 25 May

This article first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue