At Selma Feriani in Tunis, Monia Ben Hamouda’s exhibition Ya’aburnee, curated by Anissa Touati, explores senses of homeland longing and fragmenting identities

The latest iteration of the Selma Feriani Gallery is still fairly new to Tunis; the property opened in early 2024, occupying a purpose-built space in the sleepy domestic suburb of La Goulette to the north of the city. Suitably modern, the gallery is defined by soaring concrete ceilings, glimmering bright lights and spindly rectangular pillars. Ordinarily it feels airy and expansive. Yet Monia Ben Hamouda’s current solo exhibition, Ya’aburnee, has managed to introduce a markedly cramped atmosphere to the space.

A series of nine generously sized landscapes occupy the main gallery space. Three are hung from the wall, with the other six strewn out across the floor. Slightly elevated, the pieces are interspersed with mounds of slate-grey bricks. The two central concrete pillars of the gallery only crowd the floor space further; as I traverse between each piece, I feel as though I am trespassing through a tightly wound maze. This layout, evoking a crammed graveyard full of flat slab tomb markers and headstones, is a clever nod to the exhibition’s name, literally translating to ‘you bury me’, ya’aburnee expresses the desire to die before the one you love so as to avoid living in a world without them. From the get go, Ben Hamouda manages to introduce the core themes of the exhibition – love, sacrifice and ancestral memory.

The gallery space has also been leveraged to evoke religious symbolism. Visitors are encouraged to view the landscapes from a bird’s-eye view offered on the first floor. Here, the artist draws on the female experience of visiting the mezzanine level of a mosque, from where women are traditionally encouraged to worship. Music compounds the experience, with recordings from two mosques merged with public news announcements. The result is hauntingly stirring; themes of shared spirituality are merged with the despair of modern-day politics. Ben Hamouda’s other central theme – the nature of crisis and fragmentation across various lands – is immediately evident.

Image courtesy of the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery

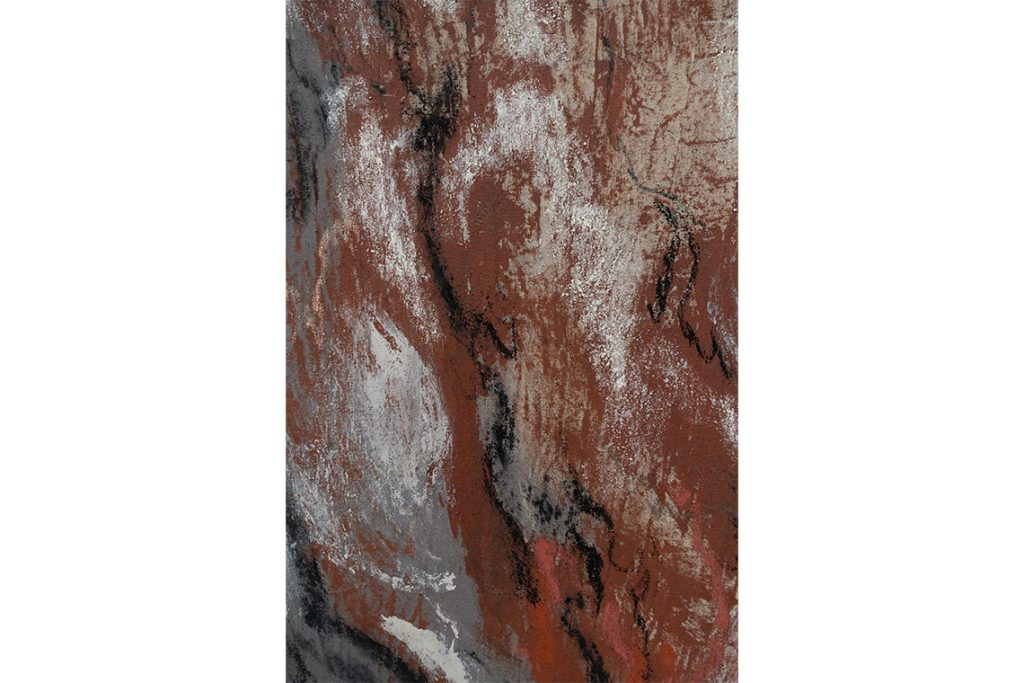

The landscape pieces themselves are crowded and then suddenly empty; swirls of terracotta are interspersed with neutral splatters – grey, beige and eggshell, with the occasional burnt orange. The colours rudely interrupt each other whilst simultaneously curling delicately together, an off-putting effect that only throws the sparser areas of the canvas into greater light. In these vacant pauses, Ben Hamouda forces the viewer to focus on the medium alone; spices, clay, soil and charcoal have all been painstakingly strewn over freshly boiled linen in order to ensure that they leave their mark.

Each material carries symbolic weight. The soil ties to themes of burial and ancestral legacy; the clay and charcoal evoke images of artistic cultural heritage; and the spices reference a familiar sense of homely abundance linked to timeworn culinary traditions. All of these materials, bound by their earthly tones and grounded neutrality, create seemingly unassuming and unplaceable landscapes. In doing so, Ben Hamouda ensures that each viewer is able to find an aspect of familiarity in her work. The series, entitled Blindness, Blossom and Desertification (2025), acts as an adept commentary on the connection people feel to their homeland – even after years away.

Image courtesy of the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery

The artist’s own experience is cleverly woven into this series of landscapes. Born to an Italian mother and Tunisian father, Ben Hamouda spent her childhood in Milan. During the summer holidays, she would often visit her father’s hometown of Kairouan, where she now has her own studio. The nine pieces forming Blindness, Blossom and Desertification are each fragmented across two canvases, a stark dark gap seemingly separating the land depicted. This move mirrors the artist’s own personal divide between different homelands whilst also prompting the viewer to reflect on their own personal experiences. For my own part, the demarcation elicited images of the ongoing destruction of ancestral lands and the borders imposed on territories across the world.

Similar themes of identity and fragmentation are explored in Untranslated Fragment I and Untranslated Fragment II (both 2025). These two sculptures, carved from beige Thala marble, are partly inspired by ancient artefacts. The similarity to the ancient Rosetta Stone, which was used to decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, seemingly suggests a bridge between cultures and heightened communication. These themes are cleverly undercut by the completely unrecognisable script carved onto the marble sculptures, however. Not only does this juxtaposition point to the plurality and diversity of language, but it also highlights the difficulty one can have understanding various different dialects. Fragmented in clean-cut lines, these sculptures also underline an ongoing breakdown in communication in the modern world. When tied in with the wider themes of Ya’aburnee, Ben Hamouda’s final sculptures ensure that visitors leave the gallery with a hefty set of questions. The meaning of belonging to a homeland, ancestral trauma and memory in the face of dispossession – they all weigh on my mind for the rest of the day.

Image courtesy of the artist and Selma Feriani Gallery