The founding director of Rhizome, discusses how he and his team adopt a proactive approach to reframing the way in which artists think about expression.

Canvas: Rhizome is a gallery and art organisation that hosts residencies, workshops and provides funding. It first launched in 2017, adopting a permanent home in Algiers in 2020. What sparked its creation?

Khaled Bouzidi: I don’t come from an art background myself, but I was working in different art and cultural collectives in France after finishing my studies in 2018. Rhizome came out of a need I perceived when I came back to Algeria and understood the art scene here better. There were some things that I saw were lacking, and following encounters with artists and cultural actors, I decided to launch Rhizome. Initially, it was not an art gallery. The first idea was to support artists achieve greater visibility, both in and outside the country. We started by accompanying them through projects, helping them to get funding and then showing their work. Little by little, we realised that there is an important lack of space in the Algerian art scene, so we decided to open our own physical space, which was during Covid-19, actually.

What were the main challenges facing artists?

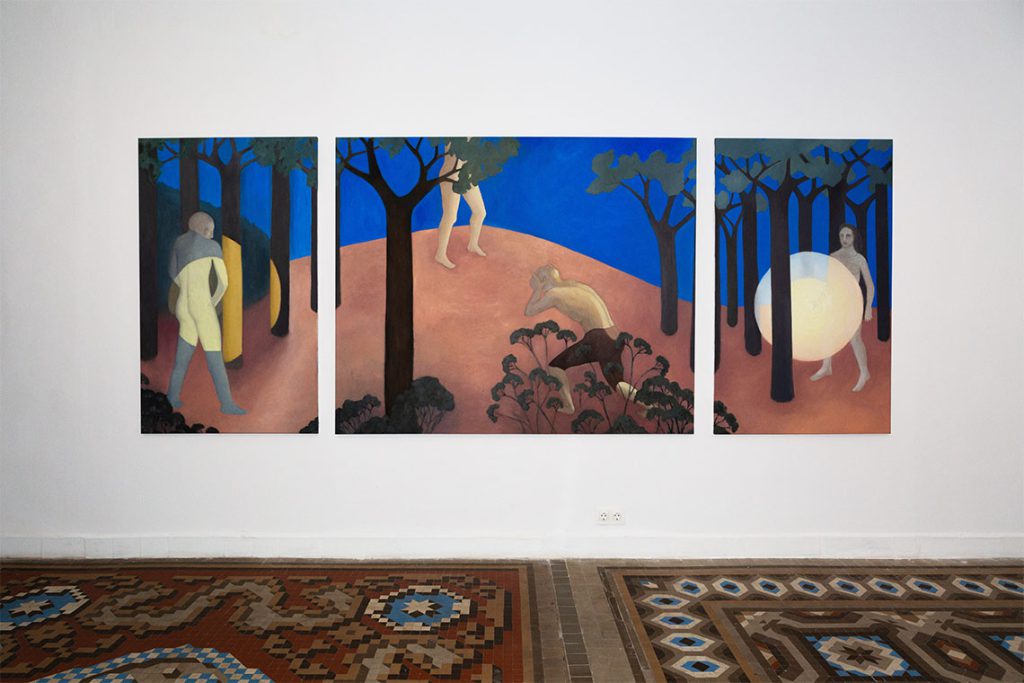

These have remained largely the same throughout, foremost being the lack of spaces and visibility. This is a scene unlike most others, even those in neighbouring countries like Morocco or Tunisia, where there are actually many initiatives, some private or independent, and sometimes long lasting. In Algeria, the Ministry of Culture is the only ‘entrepreneur’, I would say, but there are lots of problems with that. There is also the issue of education. There are probably more schools here than in most other countries of the Maghreb, something that Algeria inherited from colonialism, but the programmes also date from that time and are really disconnected from the current needs of artists. People are still studying miniatures. There is no new media, no performance. We are trying to tackle this through our programming at Rhizome – for example, by inviting artists from the diaspora who have practices that are uncommon within the Algerian scene. Most of the artists you see locally, or at least the ones who graduate from the art schools, are usually into painting. That’s because it’s the only thing they see. We’re trying to open things up, to break that cycle, or at least show that there are other options.

How fluid does the role of galleries, institutions, mentors and patrons need to be?

This question reminds me of a conversation I had with Koyo Kouoh, who founded RAW Material Company in Dakar. She said that building an institution in such contexts, in the African continent in general, is a curatorial practice in itself. You need to understand and adapt your programming to what the scene has to offer and what you can do with it. This has fuelled everything we’ve done at Rhizome since we opened.

What is the biggest obstacle you have had to overcome?

Mostly funding. For the last two years, I’ve felt that the global art system does not resonate with our ambitions. I don’t feel like we fit into this art market, so we are reducing our gallery side. Now, we mostly work with and sell to institutions. We don’t participate in art fairs anymore because it’s massively expensive. There’s also the fact that you cannot bring foreign funding into the country. That’s why we needed to open in Europe, which we did in Bordeaux. So now, Rhizome’s core activity is residencies and workshops, and focusing on the younger generation of artists.

How best can institutions and art organisations help develop the scene?

I don’t know if it’s applicable everywhere, but I feel that when there is not much going on – and you feel this every day from the art community – people ask for more, for different things. Obviously you need to respond to that, because otherwise what is the role of an institution? There are also educational needs, such as providing an educational base for the scene to grow. If I look at the market itself, most collectors in the country would buy Orientalist artwork, not contemporary. They see them everywhere else, in the bigger institutions around the world, but this is not changing the market. It’s all about education, which takes time, but it’s the only way to do it. To make a long-lasting impact, we need to work from the ground up with the younger generation of artists, some of whom are really shaking up the scene.

Rhizome has worked collaboratively on recent projects such as 1000 Socialist Villages (2023) and Libyan-Algerian Cross-Border Infrastructure (2024). How did these initiatives come about?

The Libyan project in collaboration with Merath in Tripoli is really important to us. If you look at the Maghreb and take out Tunisia and Morocco – which have many private and independent initiatives, art centres and galleries – Algeria and Libya are really on the margins. We had been trying for some time to collaborate with the rest of the region, but it was really hard, for example, to find artists from Libya, because most of them have left the country. For me, it was a dream to link up with Libya, because even though we are neighbouring countries, there’s no connection between the two. So, with Moad Musbahi, the Tunis-based artist and curator, we thought the most important thing would be to research what kind of base can be created to allow thinkers and artists to come to our scene and be interested in what’s here. For example, Algeria has a long tradition of craft, so we thought maybe this is a good way to start. More broadly, the project seeks to explore themes around heritage, finance and gender dynamics.

1000 Socialist Villages was a project initiated with the artist Massinissa Selmani. It was his idea, actually. Back in the 1960s and 70s, the period of what we call the “Algerian Mecca Revolutionaries”, the country used to be an epicentre of radical ideas. The intellectual scene today is almost non-existent, with limited exchange between different disciplines, such as cinematographers, intellectuals and artists. This project was a way of showing that there is something to look at here, of saying to artists who might be thinking of moving to Europe, “There is a lot that you can work with here in Algeria, there are other things that we can think about, other ways of creating.”

What are you working on right now and what areas do you see as requiring attention in future?

At the moment we are focusing mostly on our residency programme, for which we are launching a new call in the next few weeks. I’m also working on a curatorial project for the Art Explora Festival, a museum boat that is touring the Mediterranean. It has already been to Malta, Morocco, Spain, soon to Albania, and will reach Algeria in May 2026. As for the future, there are some topics that are appealing to the Western market and that everyone needs to work on, but there are also other things to address. The period of post-independence in Algeria, the 1960s and 70s, are really under researched, for example, as is pre colonial Algeria. These are subjects that are not necessarily endorsed within Western art institutions but which are crucial. It’s the role of an art institution and art practitioners to show that there are other ways to think about and make art beyond what an institution asks. This is where Rhizome can make a difference.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue