In her exhibition Are your memories of me enough for you? at 421 Arts Campus in Abu Dhabi, Alla Abdunabi explores the lion as a symbol of colonial exploitation and control.

A longtime victim of human persecution, the Barbary lion has been extinct since at least the 1950s. Once the largest predatory mammal roaming North Africa, this distinct subspecies of African lion was native to the forests and mountains of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. Traditionally regarded as a symbol of strength, freedom and bravery, it was both an enduring icon and an object of ‘entertainment’, captured by the Romans for use in gladiatorial combat and other grotesque spectacles and, later, systematically targeted and hunted by so-called sportsmen during the colonial era.

The historical mistreatment and exploitation of these majestic cats are being explored in a conceptual and research-led exhibition entitled Are your memories of me enough for you? by the emerging Libyan artist Alla Abdunabi at the Abu Dhabi arts space, 421. Abdunabi’s first solo show features a selection of sculptures and hanging works that were produced as part of the space’s annual 421 Artistic Development Program, pushing young artists “to explore new techniques, test ideas, and create a cohesive body of work for their first solo exhibition”.

Photography by Ismail Noor / Seeing Things Studio. Image courtesy of 421 Arts Campus

Abdunabi tackles the contentious theme of colonialism through the plight of the Barbary lion and its place in contemporary public spheres, particularly Western museums. Some institutions have taxidermy specimens, while others (such as the Tower of London) have displayed lion skulls for the public to see. In a world where ethical and moral concerns over the presentation of human remains, such as ancient Egyptian mummies, are increasingly aired, Abdunabi seemingly broadens the debate to include any object gathered during the colonial era. “The exhibition questions the ethics of restoring and displaying colonial artifacts and symbols, probing what it means to “care” for such objects, formed by the touch of empire, burdened by its legacy,” reads an exhibition wall text.

The main artworks in the exhibition are lying on the ground in a quiet setting: two of Abdunabi’s white lion sculptures are resting on beds of salt. Being brought back to life, they could be resting peacefully or awaiting their dismal fate. It looks as if Abdunabi has washed them of their aggressive and exotic nature (as portrayed in the Orientalist paintings of the French Romantic artist Eugène Delacroix) and re-presented them purely as vulnerable subjects. According to information provided in the exhibition, during the era of colonised Algeria the lions were subjected to continuous hunting by the French, an onslaught that was “seen as both a right and a means of asserting power. In this rendering, the Barbary lions are caught in the moment between their fame and extinction. As they fall away from the enforced rule of imperial guardians, they reclaim life in stillness. No longer hunted or celebrated, their raw, unfinished bodies assert their right to be, to let be.”

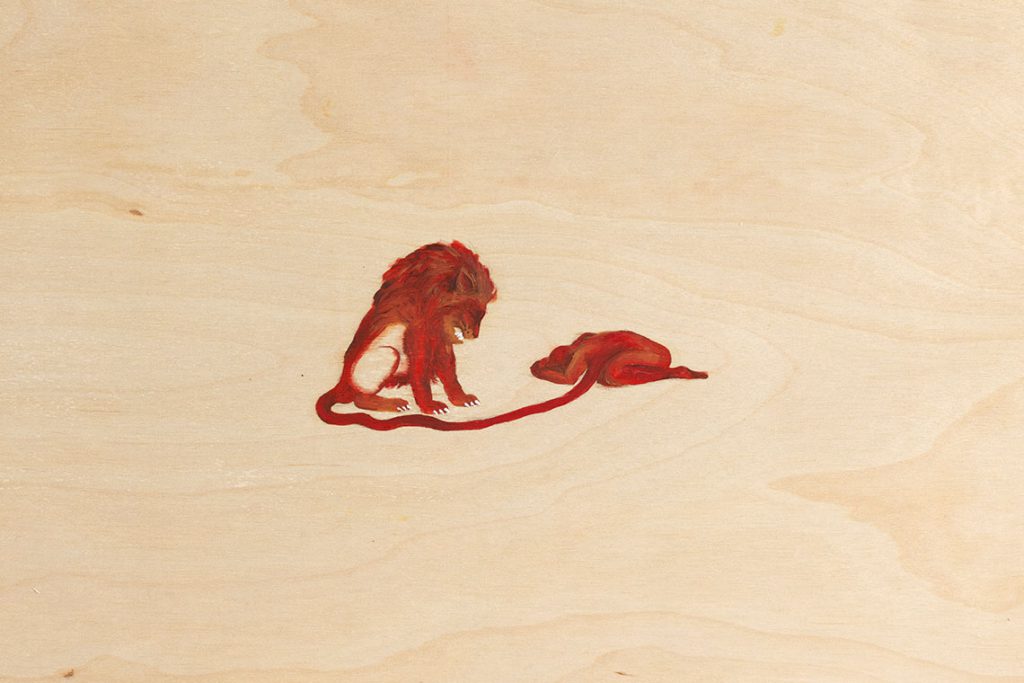

In another part of the space, Abdunabi presents an intimate series of red-coloured drawings on wood, imagining the longheld and complex relationship between the ‘dominant’ lion and the ‘vulnerable’ man. She depicts them as one, inseparable from each other. “Here, the lions are hosts for sleeping bodies. They possess, in an act of decolonial imagination, an interior depth,” according to the exhibition text.

Abdunabi’s show is also a personal affair, using objects from her own life. In one curious display, tooth and a folly (2024), a single tooth is shown. It apparently belonged to Abdunabi and was kept by her father. Through this gesture, exploring remains of the human body, she questions the notions of ownership, of the interface between the private and the public: “What belongs to whom – when and to what end.” This idea of “aggression manifest by means of caretaking” is linked to the context of the Barbary lion, which was “owned” in several ways by the Western world. This part of the display feels more abstract and unclear in its direction, inviting different means of interpretation. Could the artist be hinting at the system of patriarchy, another form of undesirable control to which women have fallen to victim? Perhaps the exhibition text offers a clue: “Preservation often functioned as an instrument of political expedience. By focalising teeth, it engages with the subtle aggression that infuses the private familial gesture when it enters an economy of extraction, selective attention, and public display.”

Elsewhere, hanging on the walls is a series entitled taste sweet, taste bitter (2024), comprising decorative, concrete grey relief structures. Like piped icing on a cake, they render ornamental patterns inspired by those found in the ancient Roman ruins of Libya, where efforts were made to protect the country’s “golden” European heritage. Bearing in mind the title of the work, Abdunabi is encouraging her audience to consider how there is usually more than meets the eye, and that by looking past the beautiful façade and sweetness of things a system of blemishes and flaws may be glimpsed. So it is that, through a minimalist approach, Abdunabi quietly reopens the nuanced discussion around colonialism and its legacy. By looking into its impact on the animal kingdom, she embraces an angle of history that has traditionally been ignored but which may have something to bring to the conversation. Certainly, when walking away from the exhibition, one questions who really is the brute: man or beast?