In the exhibition Aisha at B7L9 in La Marsa, Yumna Al-Arashi focuses her lens on women who wear ancestral tattoos in an expression of cultural physicality.

Yemeni-Egyptian-American photographer and filmmaker Yumna Al-Arashi launched her debut monograph, Aisha, in September last year. The 392-page book stemmed from a personal project; after looking at photographic images of her great-grandmother, Aisha, Al-Arashi realised that she could not see the delicate tattoos that once adorned her face. Worn by time and of relatively low quality, these physical memories left no trace of the practice that tied Al-Arashi’s grandmother to a myriad of other women in the region. Determined to research the ancestral tradition, the artist began to look into colonial archives in London. These representations, all too often centred around violent narratives that orientalised and sexualised colonised populations, failed to encapsulate the woman whom Al-Arashi had known.

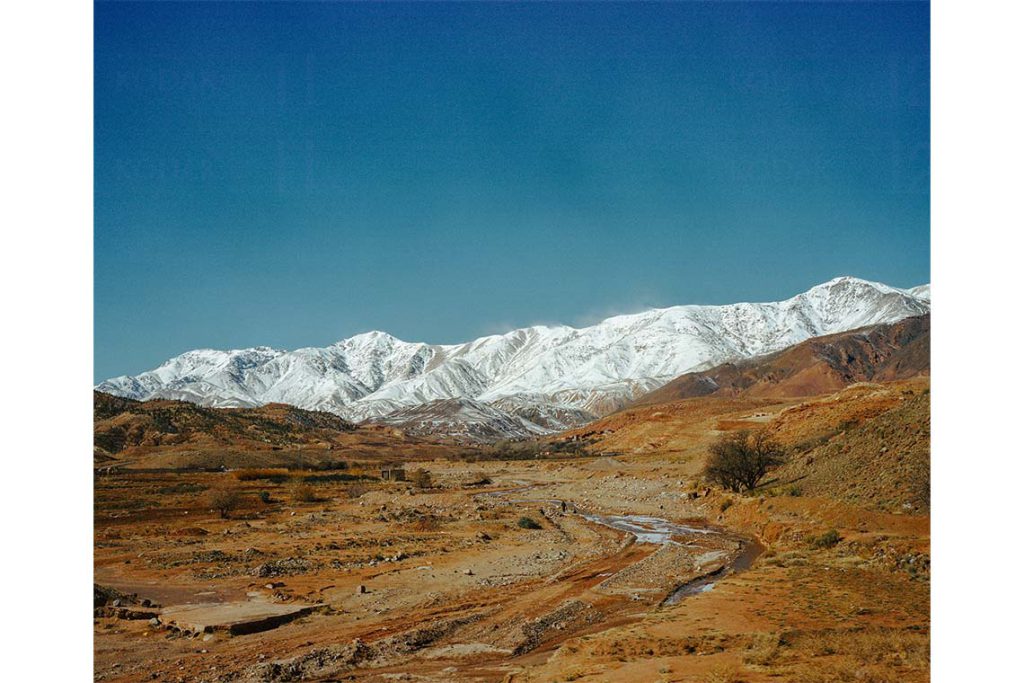

B7L9’s latest exhibition, Aisha, presents a selection of images from Al-Arashi’s debut book and aims to challenge the colonial documentation of these ancestral tattoos. Unable to travel to war-stricken Yemen, she took the photographs over a three-year period spent travelling across North Africa. Visitors are confronted with the scope of this journey upon entering the space; sweeping landscapes are suspended from the ceiling in the centre of the exhibition. Mountains smattered with snow, glittering bodies of water and valleys sparsely peppered with trees are all captured by Al-Arashi. The mark of man is occasionally present, with harsh road signs in claret red and scrapped steel interrupting the frame. These landscapes, suspended in the centre of a space filled with lively portraits, manage to ground the exhibition’s central themes of heritage, tradition, and ancestral memory.

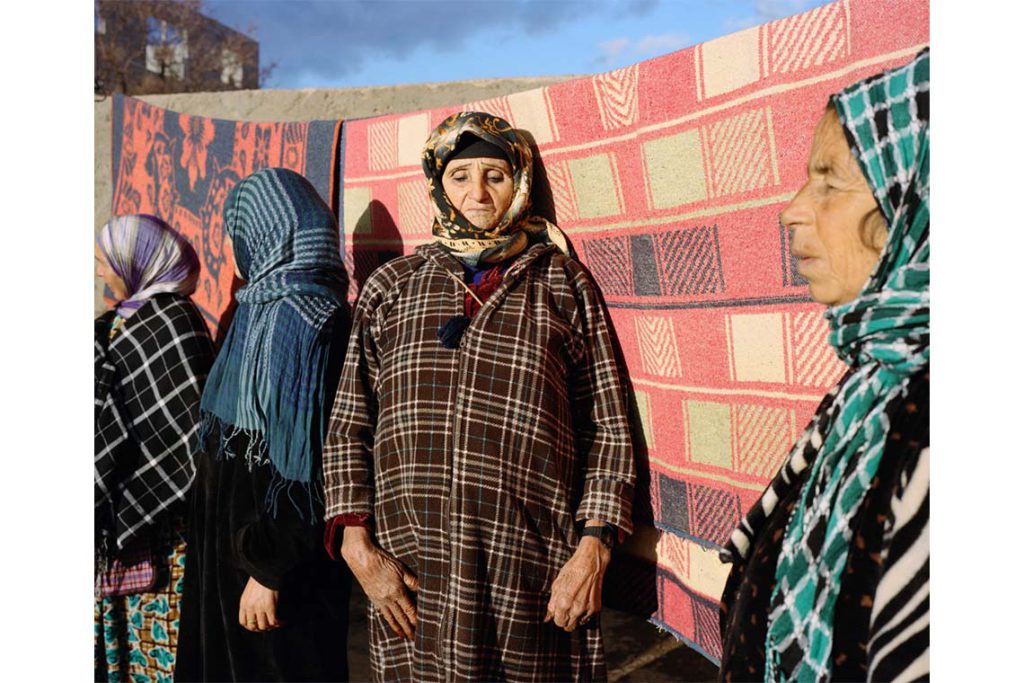

The portraits themselves are often intimate. Women are captured staring directly at the camera, their gaze unwavering and often proud. Across their faces, various ancestral tattoos are etched, although Al-Arashi makes no attempt to define, categorise or comment on these pieces of body art. The decision stands in stark contradiction to other archives on the practice, where researchers often comment on behalf of the women they are photographing. In Aisha, the viewer is instead encouraged to contemplate the women’s multifaceted identities alongside the marks imprinted on their bodies.

Al-Arashi cleverly ensures that this wider context is presented throughout her images. Alongside the central landscapes, many of the portraits illustrate the women in their daily environment. One portrait depicts a lady bundled in a chequered woollen shawl atop a similarly adorned donkey. Behind them, foliage breaks the surface of snow-capped mountains, a bleak overdrawn sky looming overhead. Another portrays two women and two children atop of a cart. A donkey begrudgingly pulls them at the front, the central woman’s face framed by a colourful headscarf as she pulls a scrunched smile for the camera. Behind them, the backdrop is defined by spindly trees and sun-drenched soil. Viewers have to peer closely to make out any trace of the subject’s ancestral tattoos. By including these pieces, Al-Arashi ties the women and their ancestral practices to the land.

The subjects are also pictured in their homes, with washing hung up behind them or accompanied by a pet cat. In other images, the women are pictured together or with family members in the foreground. Their relationships are made clear through their proximity; in one, two women stand side by side bearing matching striped woollen shawls. A sense of community, connection and shared joy leaps from the frame. Various emotions are clear throughout the series, too. In some images the women appear relaxed in front of the camera, bearing their faces with pride. In one particularly striking piece, the women’s eyes are filled with tears – an exhibition guide reveals that her son was telling her that she should be ashamed of having tattoos as Al-Arashi took the image.

The body of work in Aisha stands in direct contradiction to the reductive impulses of Western archiving, whereby researchers often extract only a handful of photographs that suit their purposes. Al-Arashi’s book features every single image captured throughout the project. To ensure visitors have access to the whole body of work, references to the book and copies of it are thoughtfully presented throughout the exhibition space, with full-bodied portraits and landscapes alongside musings and poetry pieces by Al-Arashi.

In order to comprehensively honour the multifaceted nature of these women and their histories, Al-Arashi also places a series of black-and-white miniature prints at the end of the show. These document moments from the artist’s journey – views from the road, inside the homes of the women, even snapshots of Al-Arashi. We see scenes of families cooking, people performing music and watching TV. A sense of familiarity and homely abundance is evoked, with images repeatedly taken over the course of a few moments in order to illustrate the movement and fluidity of the lives in the lens. We see Al-Arashi talking with these women, often sharing meals with them or staying the night; it is clear that the collection of images is the result of authentic encounters fuelled by a sense of collaboration and agency. Along a final wall, text marks the names of all the women pictured. It is a final act of remembrance honouring their involvement in an exhibition that, consistently grounded and all-encompassing, pays thought-provoking tribute to an ancient practice and those who strive to keep it alive.