At Christie’s London, the largest exhibition to date of works by Marwan Kassab-Bachi sees the late Syrian artist’s legacy being given new life.

Marwan: A Soul in Exile is the third in a series of non-selling summer exhibitions at Christie’s in London highlighting art from the Arab world. With over 150 works gathered across two floors of the auction house, A Soul in Exile is the largest exhibition to date dedicated to Syrian-born artist Marwan Kassab-Bachi, usually known simply as Marwan, who passed away in Berlin in 2016.

Curator Dr Ridha Moumni explains that “the aim of these exhibitions is to show an artistic scene that is less well-known to the wider public”. He sees Marwan as an artist of a “rare dexterity, unique and atypical in the history of art, who set himself apart from the rest, being Arab but also European and Western.” This straddling of two worlds, the native Syria, which he left in 1957, and Germany, where he would ultimately settle and live out the remainder of his life, had a profound effect on the artist, both personally and professionally.

The darkness in the first main room of the exhibition brings us straight away into the darkly meditative psyche of Marwan upon arrival in the grey divided city of Cold War Berlin. These initial portraits, all of a lone figure based on the artist himself, are filled with a pervasive sense of alienation and discomfort. The distortion of bodily proportions throughout, as in Sitzender (Seated Man) (1966) or Stehender (Standing Man) (1966), with heads larger than life, alludes to the mental load of unsettled identity. In the dimly lit room, we feel the bleakness he must have felt in Berlin, the psychological tension of otherness physically embodied, particularly in Stehender (Standing Man). Here, the male figure stands tense behind a table, a hand we do not see reaching below, perhaps echoing a sense of sexual frustration and repression wrapped up in this discomfort, which feels all the more intimate than exposed for the shrouding of it.

There is something intimate about these early portraits, perhaps because the figure, although purposefully distorted across the portraits, feels physically closer to the artist himself than the later years of his work, where the stretched and expanded contours of the body would take on even greater dimension, spilling across the canvas in Marwan’s famed Facial Landscapes.

In tandem with this renewed interest in the human psyche that characterised Marwan’s early work in Berlin, a broader interest in the politics of the region he had left is notable during this time. Moumni describes Marwan’s youth in Syria as “profoundly impactful, with the relationship to the territory, the earth, the landscape, the people and Arab culture remaining present, even though he wouldn’t go back to Syria for over a decade after arriving in Germany.” One painting in particular, Drei palästinensische Jungen (Three Palestinian Boys) (1970), illustrates this unwavering attention to the politics of the wider Levant region. In an inversion of the artist’s typically disproportionately large heads, the three boys are depicted as if viewed from below, heads small atop their bodies, almost frail, as these young men grapple with the turmoil of displacement from their land.

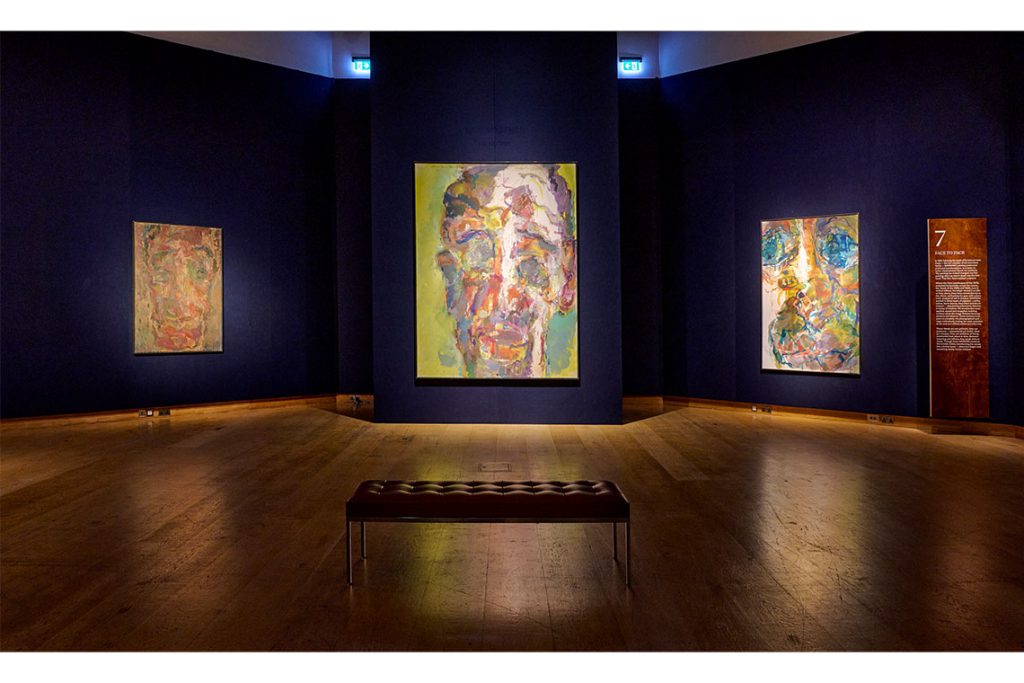

The theme of exile would take on a new visual form for Marwan in the 1970s, with the flesh of the face expanding across his canvases, losing recognisable human form to become emotional topographies in what he would call Facial Landscapes. Marwan’s work from this time is, and there is no other word for it, beautiful. The faces are luminous and undulating, featuring almost sensual pouts and rich rolling hills of flesh.

Painted over and over again, these Facial Landscapes would become the subject of a mid-career retrospective in 1976 at the Große Orangerie Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin, a pivotal point in Marwan’s career. Amusingly, gracing the floor of the room dedicated to work from this exhibition is a diamond-patterned carpet, the same as one found in an archival photograph on the wall, serving to further root us in that moment in time.

The most imposing room of the exhibition features Marwan’s Heads, long rectangular canvases displayed around a circular, high-ceilinged room. The effect is vertiginous, as the colourful marks of the abstracted heads stand watch. Painted in the wake of his sister’s death in 1983, the last of his close living relatives, the heads feel like sentinels, silent but ever watchful, sombrely symbolising the loss of Marwan’s final familial tether to his homeland.

In a more modest setting next door, we are further reminded of the importance of Syria and the wider Middle East to Marwan. Archive imagery from exhibitions in the 1990s in Damascus, Amman and Cairo, and from Marwan’s time teaching at Darat al Funun, underscores “[an] intellectual and artistic connection to his land, not just to Damascus and Syria, but the Arab world more generally,” Moumni tells me.

A corridor of letters, perhaps the most intimate space of the exhibition, displays correspondence between Marwan and figures from the Arab art milieu. Marwan, in a letter to his student Said Baalbaki, describes him as creating “a fascinating world – one viewed with the eyes of both a boy and a man who is capable of yearning for what is past with all his heart.” It is a touching description, and one cannot help but think of Marwan’s own yearning, for the Syria he left in body but never in soul.

Curator Ridha Moumni’s passionate and genuine desire to share Marwan’s legacy with the world is evident at every turn in this show. Above all, A Soul in Exile is a testament to the power of place, to the unbreakable emotional links to a homeland, and a tribute to singularly expressive artist.