The Turkish-American artist’s cosmic drawings are unfettered musings on art-making and what remains behind the perceivable.

There is a balance of finish and infinity in Bilgé (Bilge Civelekoğlu Friedlaender)’s torn drawings. The soaring cosmic possibilities are cut through the line’s determined pause with a graceful acknowledgement. Rather than deadened, the clash of supposed binaries erupts into silent meditations that prove drawing’s fruitful crops on paper. Equally anonymous and undeniably personal, the late artist’s gentle abstractions, which she created between the 1970s and the late 90s, defy today’s keen appetite to know it all. They are not occupied by a systematic comprehension – with their own pace and logic, they are mysterious and strive to remain so.

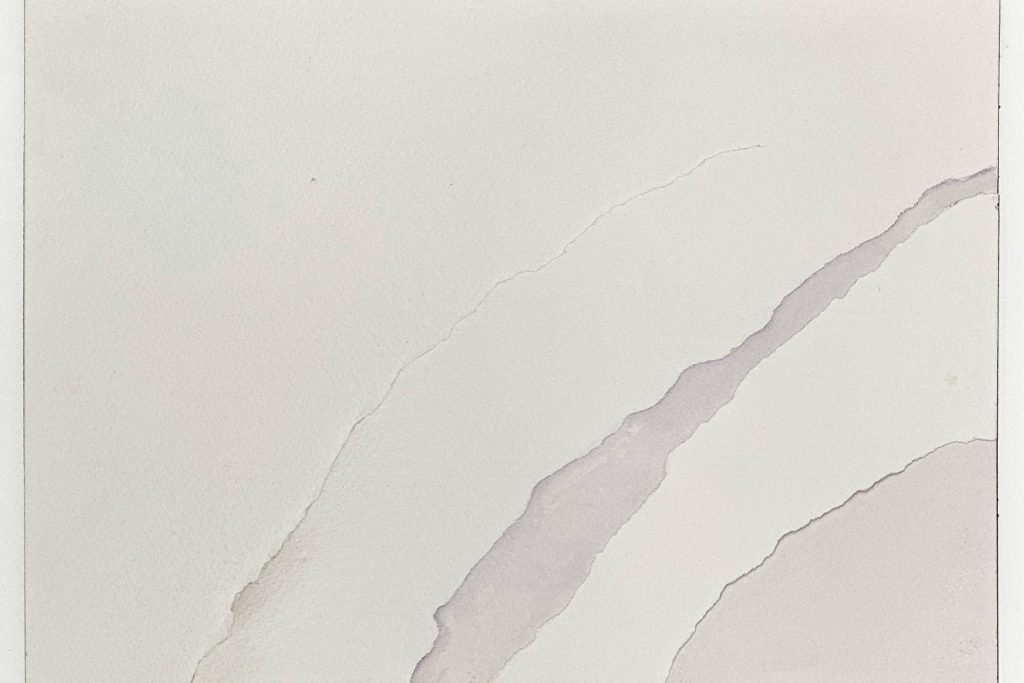

Torn Time – the Institute of Arab and Islamic Art’s intimate but absorbing survey of the artist’s work from the 1970s in New York (except for a book work from 1984), where she spent over four decades of her life – sits on Greenwich Village’s bustling Christopher Street. Amidst the neighbourhood’s heavily populated bars, parks and corners, the Turkish-born artist’s ethereal statement blows an unforeseeable summer wind. Often cursive, occasionally erratic, and mostly subtle, the lines in charcoal, pastel and watercolour marry gentle cuts of paper. Light’s moody wash bears pockets of soft gloom – like the sun’s changing command on the earth; shadows cast responses on the surface akin to fleeting expressions on an otherwise aloof face. Tide’s in #4 (1975) embodies three acts of tear in varying forces. Like an unpredictable forecast, they blow through the paper’s bottom right. They are both bolts and caresses, humming through the artist’s pencil and watercolour marks that trace their longstanding impact.

and the Estate of Bilgé

The show traces a prolific decade in Bilgé s New York years during which the likes of Agnes Martin and Ellsworth Kelly were also immersed in pushing the limitations of the line. Like those contemporaries, she showed at Betty Parsons and exhibited at MoMA, but perhaps a foreignness – both of her bureaucratic identity and the quietness of her lexicon – kept her away from the spotlight they enjoyed. Bilgé’s plunge into transcendental spans of abstraction feels more tender on the hand. Begging for an intimate inspection is a shared trait between the artist and her peers, but in her case sits a foundation of spatial refusal. Arrestingly intimate layouts in demure hues defy dominant exhibition strategies; enigmatic compositions both invite and look away. She frees her lines and tears from a material burden, refusing to teeter on the brink of explicability. The earthiness of the paper is ceaselessly tried, its alchemy being tested for optic wonders.

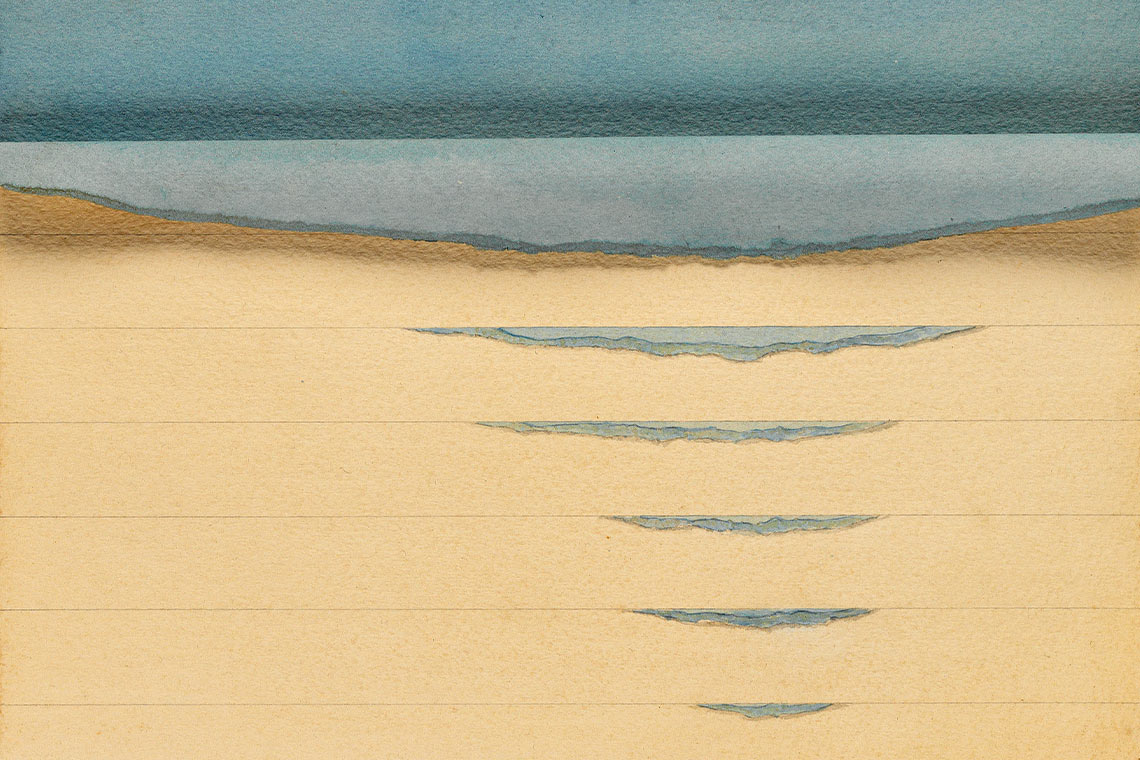

In Tides Time II (1975), the horizontality suggests an idea of a place, perhaps a sky bleeding into a seashore. The watery blue on top of the composition is eventually folded, from which the creamy white starts all the way to the bottom. The suggestion of a tear where the blue bows out is a faint one, almost like a secret shared between a lucky few. The brutality of stripping one piece off the other is eased by Bilgé’s soft command. Blue lines continue to echo over white, like ripples on a water surface. Instead of circular, here in her imagination they are lines that start long and gradually wane into a minuscule gesture. Whether a Turkish cove or an ocean view, the locale in mind remains opaque. Nature casts its spectral impression in Blue Time (1974), a mountainous landscape in an aquatic hue. Decades later, watercolour’s inherent wetness still feels palpable through the cursive lines that rise and fall on both ends of the paper like two suns bulging behind twin mounts. The monochromatic all-blue undertaking renders suggestions of sky or sea open-ended and comforts us in the joy of internalising a composition of soft geometry.

and the Estate of Bilgé

Bilgé’s oeuvre, some of which are in the holdings of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, RISD Museum and the Menil Collection, bestows an invitation to absorb the visible with the promise of more through the tears. The show’s titular work (1974) and the same year’s Torn Time #5 embody the potential potential of a rip as a gesture of drawing. Both horizontal, they hold flat lines in charcoal, watercolour and pencil. The ruptures bear breaths of depth which gives the drawings a kinetic subtlety. Bilgé’s hand still hovers over them at the institute: through the immediacy of her tears, her intention still feels deliberate yet with a trust in the path that a tear pursues across the paper.