A comprehensive group exhibition in upstate New York traces the overlooked history of the post-liberation Iraqi movement known as the Baghdad Modern Art Group.

Art owes its resonance as an alternative outlet to history for its holistic embodiment of its times. Fashion helps future generations understand the ways people of a certain era sourced materials and utilised function for form; architecture or food frame how communities dabbled in sensory stimulations within the means of their surroundings. Any form of art, however, operates unrestrained from the burdens of an immediate purpose and lands on the thin line between a reality-imposed logic and its intentional refusal. Think the post-First World War emergence of Surrealism, or Dansaekhwa in the years after the Korean War.

The Baghdad Modern Art Group emerged on a similar breakage after Iraq emancipated itself from Britain in 1932 and plunged into an arduous post-colonial identity construction project. If art is a microcosmos of the people at a given time, the artists of post-liberation Iraq were no exception. All Manner of Experiments: Legacies of the Baghdad Modern Art Group– an in-depth survey at the Center for Curatorial Studies (CCS) of Bard College’s Hessel Museum of Art – starts with illustrating the duality faced by the movement’s founders, Jewad Selim and Shakir Hassan Al Said, which mirrored that confronting the rest of the country. They paid deliberate attention to leaving the safe arms of tradition and heading towards a global profile, all while the urgency of reclaiming an Iraqi identity after the hardships of a two-decade mandate was undeniable.

The show, organised by Texas-based art history professor and curator Nada Shabout with help from Tiffany Floyd and CCS’s artistic director Lauren Cornell, features paintings, sculptures and drawings. Drawn both from the movement’s key figures and less-recognised artists that number around 25 in total, the show also features works that have never been previously exhibited. A plethora of ephemera from the Group’s exhibitions is also presented, including from its very first show in 1951 at the Costume Museum in Baghdad, as well as gatherings at venues such as the Baghdad Institute of Fine Arts and the National Museum of Modern Art. The works and objects solidify the roughly two-decade long movement’s operations, some of which still remain opaque due to limited documentation and the destruction of archival materials post-US invasion. The Group’s impact on the present is also recognised through the inclusion of a selection of works by contemporary Iraqi artists, some living in Baghdad and others, diasporic.

Optimism, as the show – which features over 60 artworks and tens of archival materials – suggests, was a determining factor in Selim’s and Al Said’s efforts to form a group which they called Jamaat Baghdad Lil Fan al-Hadith in Arabic in 1951. They based their perspective on transforming tradition into something new, reforming the familiar with forward-facing ideals under a veil of inspiration from their own European art education.

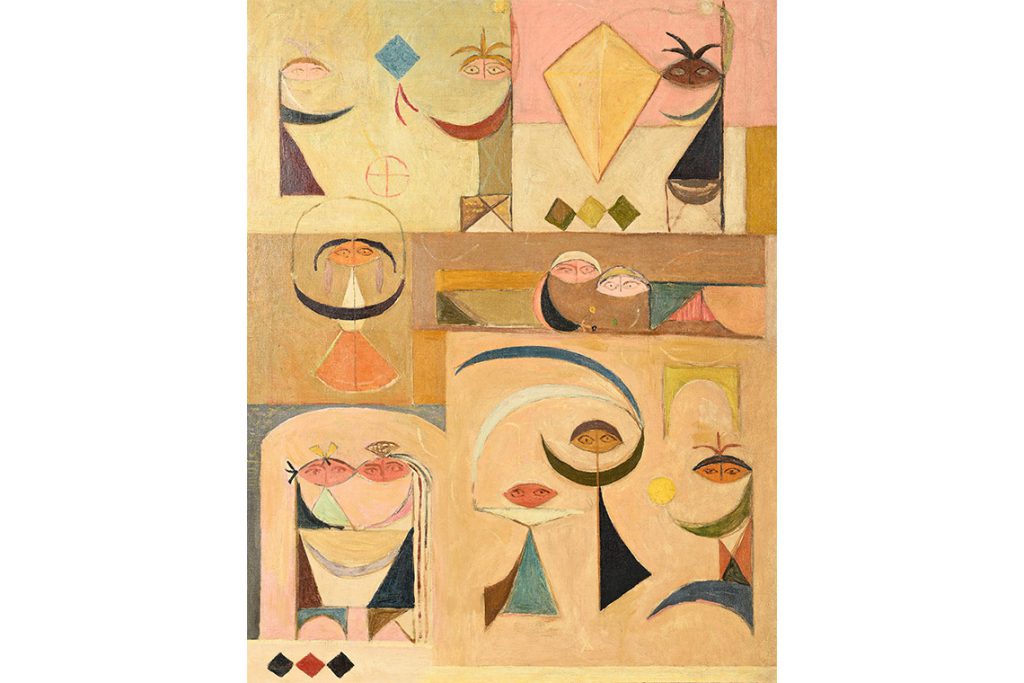

Selim’s 1953-dated painting Children’s Games initiates the show with a captivating emphasis of their ambition to reawaken the past by way of embracing the moment. A loose grid of various crescent forms alludes to Baghdad city life; moon-shaped faces are punctured with large oval eyes which echo their bodies’ limbs in form. The lunar rhythm in the Mesopotamian reliefs of 3000 BCE is revived with a dynamic assumption of abstract possibilities. Pastel tones and earthy hues are alchemised, as are familiar mundane rituals and mythic iconographies.

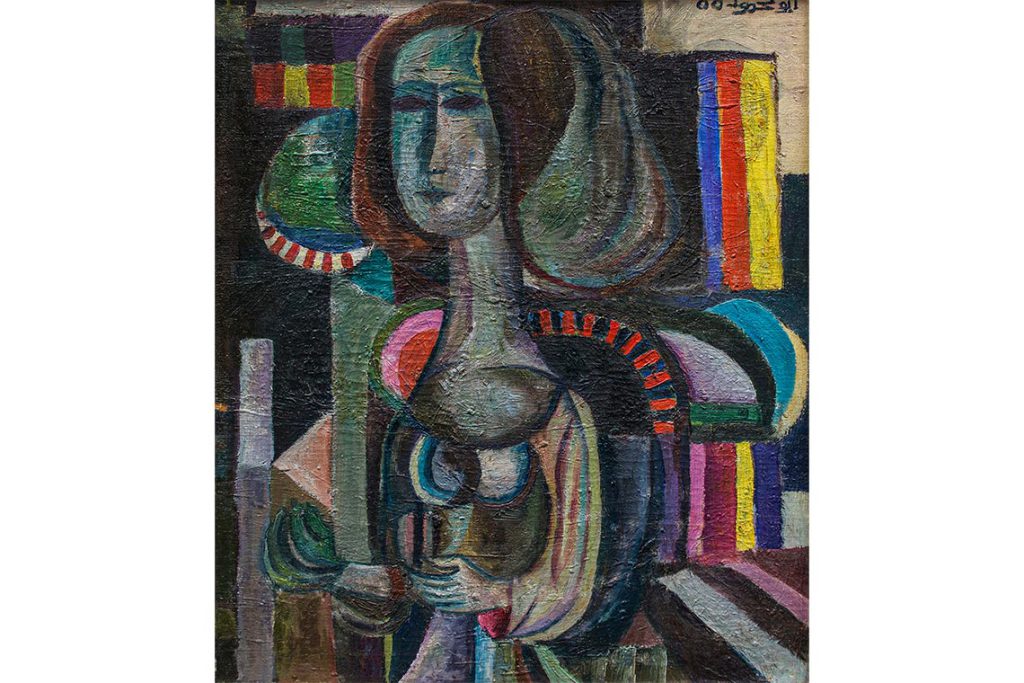

Al Said’s two paintings The Leaping (1953) and Cockerel (1954) borrow similar Islamic crescent patterns in intentional colorations – in light pastel hues in the former and thick bold shades in the latter – to build semi-figurative worlds of pure experimentation. Portrait of a Belle (1955), which he painted in 1955 before his complete transition into abstraction in 1958, utterly embodies his group’s reformative manifesto. The subject’s likeness holds an architectural form proven by her long neck and stretched face with a determined expression. With undeniable Mesopotamian traits as well as an aloofness reminiscent of a Modigliani, the sitter inhabits a contemporary autonomy, delineated by her revolting facial features, an unusually bright color palette, and an enveloping kaleidoscopic abstraction.

The show owes a part of its success to going beyond shedding light on the movement’s impact on the culture of its time by underlining the Group members’ inspiration for the ensuing generation and – similar to other post-colonial movements – cementing its legacy in other parts of the globe. The curators reserved the finale of their orchestration to diaspora artists who formed a network called Eighties Generation through the precedent set by Selim, Al Said and others. After the devastations of the Iran-Iraq War, UN sanctions and the US invasion, figures such as Mahmoud Obaidi, Nazar Yahya and Amar Dawod drifted elsewhere, and the show—beyond its other achievements—proves how the Baghdad Modern Art Group was instrumental in these younger artists’ efforts for a future that refuses to be solely defined by collective anguishes while preserving a vivid comprehension of a turbulent past.