Through the voices of migrant artists, the recent exhibition reveals remittances as acts of care and connection that transcend distance.

For diasporic migrants, ‘remittance’ is the familial duty of sending money home. As a remitting immigrant, I did not know this word is largely unfamiliar beyond our context. But in Close to Home: Remittance Spaces Between Arrival and Return at Berlin’s SAVVY Contemporary (ended 19 October), curators Patrick Jimenez Krämer and Lukas Feireiss shared this reality with a wider audience, exploring remittance beyond its economics. What lies beneath this duty, and what else do we send back? Rooted in Krämer’s research on ‘remittance architecture’ and born out of a mentorship relationship with Feireiss, the exhibition spotlighted 13 Berlin-based artists with migration backgrounds, spanning from first to third generation. Most works, exhibited here for the first time, referenced each artist’s personal relationship to remittance.

‘Remittance spaces’ then became the starting point of this exhibition. Krämer’s installation, Bahay Kubo (2025), is an architectural model of a house he built in the Philippines from his mother’s remittances. Here, the house becomes a symbol of transnational kinship and of a diaspora son remitting his learned skills and knowledge. The Filipino-German architect learned Philippine vernacular architecture as a way of reconnecting with the materiality and environment of his heritage and understanding his mother’s earnest 30-year remittance practice. In these homes, he observes that German aesthetics and appliances often permeate its interiors; another form of remittance perhaps, from his mother.

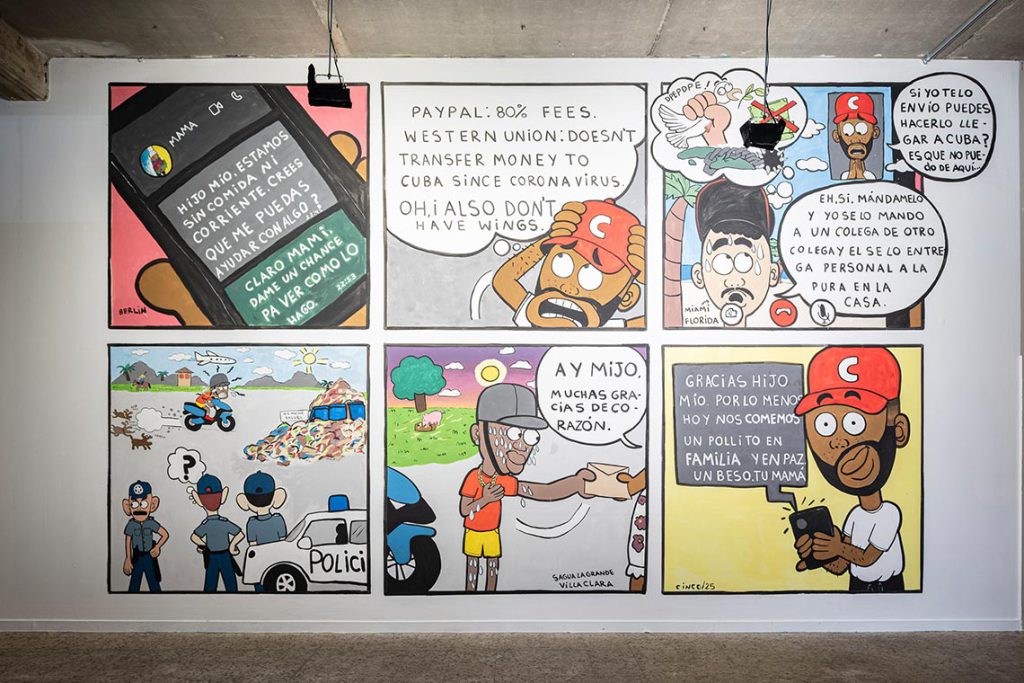

A dialogue with migrant children continues to the walls, where Cuban artist Yairan Montejo had painted The Long Way Home (2025), a large-scale comic mural on the real-life tribulations of remitting to his mother in Cuba. The obstacles of absurd transfer tariffs and lack of alternative remittance channels were temporarily remedied by transnational migrant Cuban friendships: the money transferred many-fold before arriving in Cuba as physical cash. The humour in the comics eclipsed the harrowing emotional labour that Cuban immigrants mitigate to demonstrate remittance as an act of love, glimpsing the day-to-day impact of what feels like macro political and economic affairs.

However, Indian artist Akshita Garud’s Cross My Palm With Silver (2025), created with sculptor Avantika Khanna,questions if her remittance is truly an act of love or an imposed obligation. The sculpture reflects on the ‘debt’ – in time, money, emotional labour – immigrant children often felt towards their parents. Double-ended stainless steel spoons disguised as silver reflect this duality: the industrious resilience of the former masked as the refined delicacy of the latter. “Those born without a silver spoon in their mouths must forge their own paths to prosperity,” their text read. Opposing spoon ends hold Indian food with contrasting flavour profiles, teeter on a mirror that multiplies its image endlessly. The delicate fragility in the multi-sized spoons carrry different weights of guilt and gratitude; some light and fragrant, others pungent and spilling over. The answer is perhaps not either/or, but the recognition that the co-existence of these feelings is required for balance.

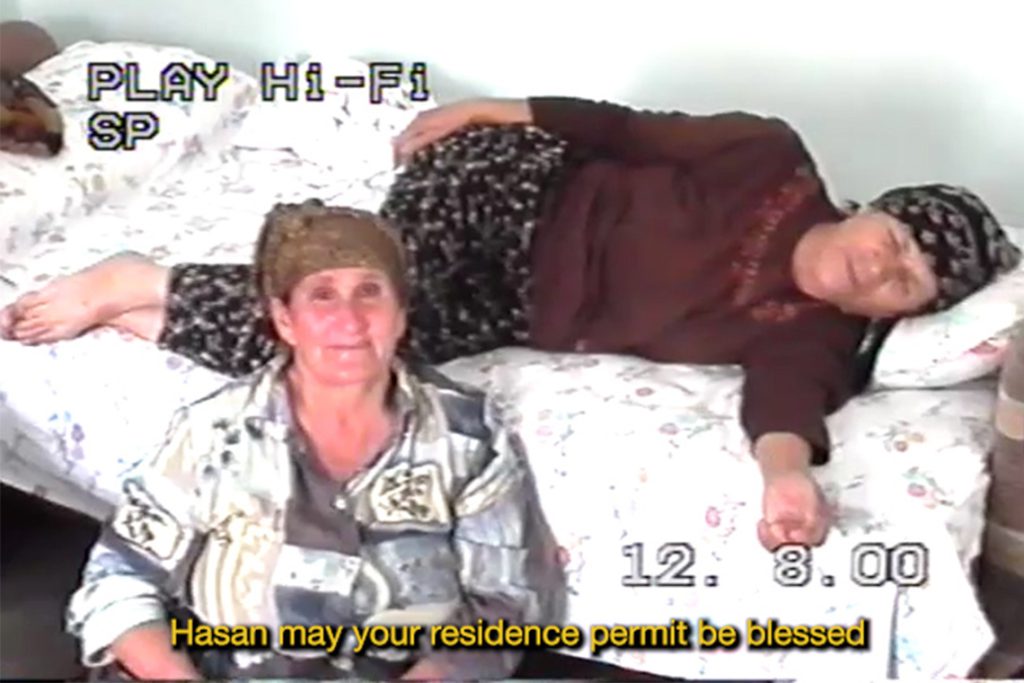

Other artists inhabit the migrant realities of their relatives. In Çavê ta paçtaka – Loss Kisses (2025), Kurdish creative director Hasan Gündoğan and architect Deniz Örün digitised more than 70 hours of their family’s video remittances stored on 1990s–2000s VHS tapes. Filmed in Pazarcık, Kurdistan, Zürich, Switzerland quotidian scenes of laughter, meals, greetings and kisses were captured by those left behind to be sent to loved ones in political asylum. The scenes in the installation are from tapes that never reached their intended recipients, the installation a memorial for a place that no longer exists in the way that the diaspora remember it. Although its protagonists are strangers and their language unfamiliar, I felt the tender longing transcend through the screen; there is a quiet grieving for their unremitted affection.

This lamenting of time and distance was carried on by Filipino artist Lizza May David’s Two Years More (2006), a documentary centring her domestic worker aunt Nerry in Hong Kong. The scenes oscillate between Nerry’s lived realities in Hong Kong and that of her family in the Philippines, eventually taking us back home with Nerry, who had not seen her family in three years. Upon arriving, Nerry searches for physical markers of time passed; her husband’s missing tooth, the deterioration of the house flooring she financed, the profitability of her rice mill and rented apartments – the latter being her investments towards her eventual return home. Hers is a lamentation of having to choose between time and survival. Sari-Sari (2025) took us to 2023: a painted portrait of David, Nerry and her family in Manila; here, Nerry finally comes home. Painted with typical Filipino non-permanent stamping ink, once used for fingerprinting on ID cards, the painting embraces its fate to vanish: physical markers of time passing.

Thai architect Van Bo Le-Mentzel’s Artist Wallidency (2025) also honours the life of his aunt Co Hanh Ngo, a Laotian Buddhist nun who lived in a five-metre-square room in a pagoda in Hanover for most of her life. A choice for modesty and self-determination, rather than poverty and precarity, her life in this tiny space enabled her to send money back to her daughter in Laos: just enough to build herself a two-storey villa, a prosperity Ngo never had. After 40 years, Ngo returned to Laos and died in the palace her remittance had built. Le-Mentzel’s installation replicates Ngo’s living quarters, perhaps conjuring a spatio-emotional experience derived from such constrictions and isolation.

Close to Home was a refreshing exhibition shedding light on the duty of remittance: a dimension of migrant life often kept private. Remittances, beyond their utilitarian function, served as tangible, enduring reminders of our care for the homes we had departed. Here, remittances did have strings attached: strings with longing, guilt, frustration and love tied to the side of the world where we had left our loved ones.