This year’s Aichi Triennale unpacks the links between humans and the environment in an effort to draw our attention to how we might move forward on a more sustainable basis.

The issue of humans and nature coexisting is a tale as old as time. However, we often lose sight of the impact we have on each other. As industrialisation grows, wars and genocide rage on and human consumption leaves its mark on the environment, so the connection between us weakens and we lose sight of our roots. This year’s Aichi Triennale, entitled A Time Between Ashes and Roses, explores these often intangible threads. It takes its name from a work by the Syrian poet Adonis, whose 1970 book was written in response to the Six Day War, which had occurred three years prior. The verses are a telling insight into the transitional state between destruction and new beginnings, preparing the ground for the triennale to unpack the complexities between a human-centric existence, the scars left on the environment and the space for new growth among the ruins.

Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, the 2025 edition opened in a world racked by political and social turmoil, as well as the ongoing climate crisis, and offers a particularly timely space for reflection on our relationships with Earth. “I wanted to do something that connects us globally, as we’re at a turning point where we can’t ignore what’s happening everywhere,” Al Qasimi shared with Canvas. “When people discuss environmental issues, it is usually to do with one aspect, such as recycling. But what about mining, extraction, bombs or loss of land?”. During the opening press conference she also noted the universal impact of current events and consequences: “I’m grateful to the triennale for allowing me to use this platform to bring artists from different parts of the world echoing the same desires, the same needs and the urgent call for us to be in solidarity and to raise our voices to support each other and end the genocide that is taking place. I echo many people when we say, none of us will be free until all of us are free. So, free Palestine. I also want to talk about how the issues that we’re looking at today don’t only reflect what is happening now but also what has been going on for generations for many indigenous communities.”

Coinciding with the opening, the prefecture saw protests regarding the Aichi-Israel Matching Program, linking local companies with tech start-ups in Israel. Although not associated formally, several artists signed an open letter urging the participating artists to demand an end to the ties: “[The triennale] must not be used to artwash the systems of corporate greed and militarization that exploit and oppress our communities and lands – from Nagoya, to the Ryukyu Islands (Okinawa), to Gaza and beyond.” Bassim Al Shaker’s work, New Birth (2025) in the Aichi Arts Center seems to encapsulate the feeling of the triennale. Paintings hang from the walls, and one from the ceiling, surrounding viewers with swirls of colour. From the surface they seem light in tone, but they express the artist’s recollection of bombs detonating in the air during the 2003 US invasion of Iraq. Yet, the paintings are not about death but living in the moments after the explosions, resilient with gratitude for life.

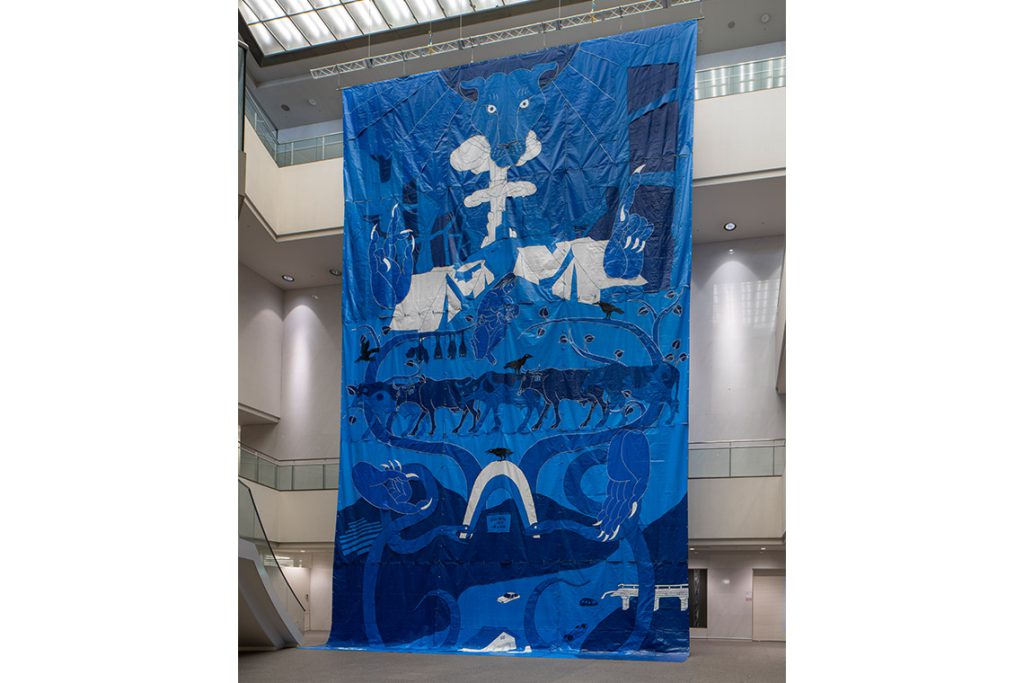

A commissioned tapestry by Kubo Hiroko, The Lion with Four Blue Hands (2025), drapes down several floors inside the building, depicting apocalyptic scenes of human-made catastrophes and climate-related disasters alongside mythologies and themes of creation and destruction. “As we mark 80 years since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it’s really important to reflect on the history of the nuclear bomb, and how what we’re seeing today is related. I think this exhibition is also a reminder that we all live under the same sky and we’re all connected in all of our issues,” Al Qasimi explained when referencing the work. Also commissioned by the triennale, Dala Nasser’s large-scale installation Noah’s Tombs (2025) recontextualises the flood story within a contemporary framework, as the sculpture combines elements from three locations in Türkiye, Jordan and Lebanon, each thought to be Noah’s burial site. The work also includes an ouroboros, a depiction of a serpent eating its own tail and symbolising cyclical nature of life, death and rebirth, as the ark becomes a monument of uncertainty yet also perhaps of hope, as a futuristic ship sailing away from disaster.

The connection to water is a strong thread through other works in the arts centre. From John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea (2015), a three-channel video merging histories and narratives as the sea operates as a space of both beauty and fear, to Mulyana’s crocheted installation, Between Currents and Bloom (2019–present), drawing attention to the severe water pollution in Indonesia and its impact on marine ecosystems, and Koretsune Sakura’s After Efflorescence: Awakening the Whale Beneath Us (2025), which brings together local myths, memories and histories between whales and humans in Aichi.

The triennale extends further than the arts centre, across several more locations including the Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum and multiple venues in Seto City. The latter locations directly link the exhibition to the local community and delve into issues around labour and industry, as the city is the location of Japan’s key ceramic industries, known for their innovation and techniques. In Seto, Robert Andrews has installed two works, Buru and What Lies Within (both 2025), in the Kasen Mine. The installations combine local clay, mechanical parts and layers of earth designed to slowly wear away for the duration of the exhibition, underlining the impact of human activity and natural forces as they make their marks on the land.

Other activations are taking place throughout the city, including Sasaki Rui’s Unforgettable Residues (2025), installed in a former public bathhouse once frequented by pottery workers. Translucent glass slabs encase the remains of plants that were collected from the area, specimens that turned to ash when they were fired in a kiln between glass sheets, leaving a trace of something that no longer exists. Adrián Villar Rojas has taken over the ground floor of the decommissioned Seto Fukugawa Elementary School with the site-specific Terrestrial Poems (2025). The location served as a site of learning for over 100 years, open from 1903 until its closure in 2020 due to depopulation and an ageing society. The walls of the school have been covered in wallpaper depicting layers of history meshed with digital textures and glitches that connect with what it means to be human. The work re-examines ancestry and realities, and how the past can be weaponised to justify political acts – disentangling the existence of life, learning and identities.

Installed outside of the Seto City Art Museum and Cultural Center, Sheikha Al Mazrou’s A THROW OF THE DICE WILL NEVER ABOLISH CHANCE (2025) blends with the location as marble is overlaid on top of the site of a former fountain drained during the pandemic. The black ripples in the material seemingly revive the water feature through this intervention, a delicate reminder of the power and impact of human activity to give and take. The works in the triennale highlight critical events and serve as a poetic reminder of the legacy of our actions through accessible dialogue. When asked about ensuring triennials and biennials remain sites for these conversations, Al Qasimi told Canvas “It’s really just about being open and transparent, and I think that’s the best way.” It is through such openness that the event seeks to become a space for reflection and conversations that go beyond the works themselves.

Aichi Triennale 2025: A Time Between Ashes and Roses runs until 30 November