The 18th Istanbul Biennial works its way through a variety of the city’s venues, occasionally losing its way but ultimately serving as a reminder of art’s value during uncertain times.

The latest Istanbul Biennial, curated by Christine Tohmé, is scattered around various locations across the Beyoğlu-Karaköy axis of Istanbul, with the eight venues all within walking distance from each other (even if some require a slightly steep uphill climb). Entitled The Three-Legged Cat, the biennial is set to unfold over the course of three years, with this year’s exhibition acting as the first “leg” of the event.

The biennial concept of the three-legged cat is an homage to the felines which famously roam the city, but strikes a rather peculiar note in terms of its relationship with the art on display. Either way, the cat’s symbolism was overshadowed during the opening days of the biennial, when both curator Christine Tohmé and Ömer M Koç of Koç Holding, the primary sponsor of the biennial, chose to emphasise the ongoing genocide in Gaza in their speeches. While distracting in some senses, the words served as a reminder of the absurd dilemma of trying to carry out business as usual while massacres continue to take place.

This irrationality was brought into sharp relief by Palestinian artist Mona Benyamin’s video work, Tomorrow, again (2023), located in Elhamra Han, a former theatre hall now housing shops and residential units. Perhaps one of the most memorable works of the entire biennial, it captures the absurdity of the news cycle as well as the Palestinian condition in Israel. In one clip, an older man laughs nervously as, behind him, clouds of smoke from bombs billow up into the air. In another excerpt, a newscaster on air starts to read out the latest tragedy, breaking down in progressively more hysterical sobs. At one point the characters, played by Benyamin’s family members, start shouting at each other during a live news broadcast. There is something cathartic about seeing these reactions play out, as if the veneer of civility has finally cracked in the face of repeated absurdity.

Just as we are thinking the world as gone mad and we may as well embrace it, a little further on from Benyamin’s work is an oversized soft sculpture of a plant/animal hybrid by Şafak Şule Kemancı, stretching its tentacles across a small room. It is a welcome moment of playfulness and respite, which is mirrored elsewhere in the biennial. Just as things get a little too dark, the unexpected pops up. In the Zihni Han location, right on Istanbul’s waterfront and the former headquarters of a shipping company, the floor is littered by a display of Abdullah Al Saadi’s sandals encased in rocks, anchoring us to an old tale from the Gulf in which local island communities would throw sandals into the sea in the hope that sand would accumulate around them, thus creating more land in the form of an island.

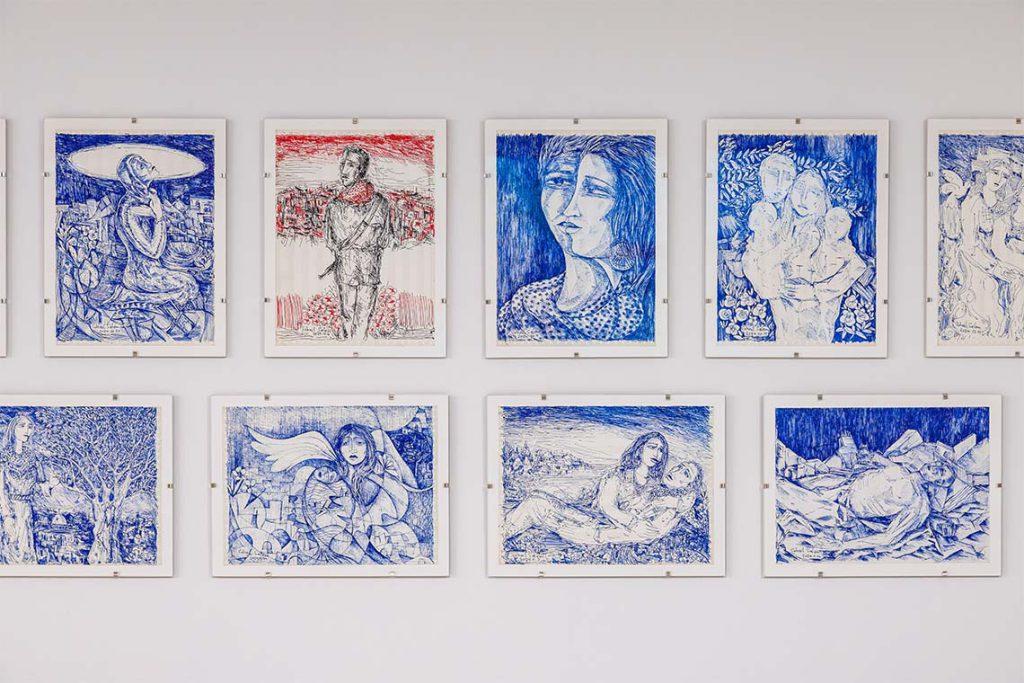

Near Al Saadi’s magnanimous flip-flops hangs a series of blue drawings by Sohail Salem. We know the theme before we even recognise it. Diaries from Gaza is a series of works on a notebook from Salem’s experience of life in the enclave under siege, the depictions of displaced Palestinians living their lives in this apocalyptic time all the more haunting for the fact that some of the drawings had to be smuggled out of Gaza to be shown here. We are dealt an emotional blow, the rawness of the pen mark on paper reminding us of the urgency of the moment.

This cycling between reality and fantasy is where the biennial really finds its footing, providing both breathing room between works and novel approaches to contentious topics. On the top floor of Zihni Han, in a bright room with large windows overlooking the Bosphorus (a welcome change from the industrially lit, low-ceilinged rooms of the rest of the building), an installation by Marwan Rechmaoui does just this. In Chasing the Sun (2023–25), the artist continues his exploration of play, examining how childhood games can provide context for how societies are built. The room is full of these “toys”, with a hopscotch, oversized toy horse and even usable swing sets creating a veritable playground for adults. It is easy to get distracted by these games and not notice the Molotov cocktail sitting unobtrusively on a low shelf at the back of the room, striking a decidedly more sinister tone.

Elsewhere, in the basement of Galeri 77, Lebanese artist Haig Aivazian’s You May Own the Lanterns but We Have the Light takes us through what we presume is a cartoon rendition of an imaginary Beirut at night. The animation styles shift from scene to scene, as we are brought into the underbelly of the world after dark, enchanted by the dulcet tones of the narrator and characters as they recount the events of the night. The video’s black-and-white graphics are indisputably alluring, while the animation styles feel like comforting vestiges of childhood, even though the subject matter exploring resistance and escapism is decidedly less soothing.

The sheer volume of work across the biennial (nearly 50 artists are participating) means that there is a lot to cover, and it sometimes difficult to access all the locales. The low-ceilinged rooms and steep winding staircases in ElHamra Han make for a slightly bumpy ride, for instance. Coupled with a disproportionate number of video works and not always enough time to properly engage with them, overall the biennial feels a little off-kilter at times. However, works like those of Aivazian, Benyamin and Salem ultimately serve as the guiding light throughout. They allow us to imagine novel approaches to present realities, while serving as necessary reminders of the importance of art. At a time when large art events can feel like a frivolous endeavour, it is in this reminder that, much like the three-legged cat, the Istanbul Biennial does eventually find its footing.