The Palestinian artist navigates the intersection of nature, memory and loss through textured landscapes. Drawing from personal histories shaped by displacement, her practice reflects on notions of home and identity.

Canvas: Nature is often seen as a witness to violence and a holder of memory. Do you see the landscapes in your work as silent observers?

Dina Nazmi Khorchid: My relationship with nature goes beyond seeing it as a peaceful or contemplative space. I think of it as something that deeply affects our wellbeing, as it’s both healing and threatening. Nature suffers alongside us in war and destruction, and I often think about ecological grief. My latest work, The Color I Hate the Most is Rubble & Smoke (2025), reflects my experience of the Beirut explosion and living with PTSD. The smoke’s colours – reds, browns, purples and rusts – are haunting and appear again in images from Gaza and of wildfires, worldwide. This inspired a handwoven piece that is partly structured and partly loose, symbolising trauma and fragmentation.

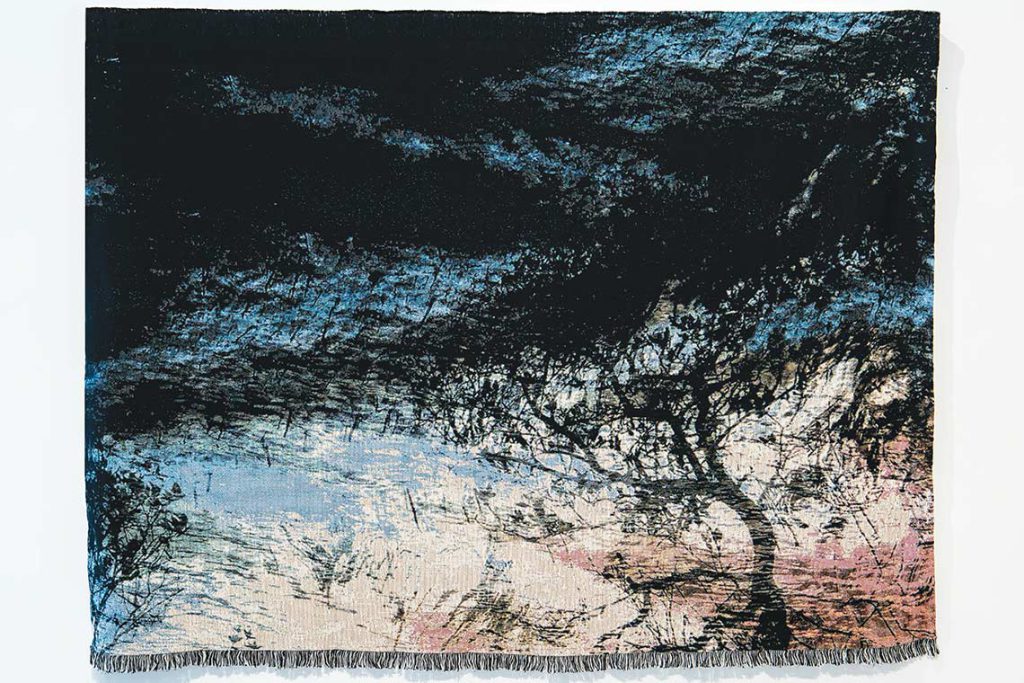

In your textile installations, such as the Land, Untitled series (2023–24), nature – and in particular trees – take on an almost ghostly presence. How do you select the elements in your tapestries?

In this series some of the elements, whether woven or printed, portray haunting trees, specifically trees that are submerged in water. What I’ve been drawn to is the reflection of trees, these solid and strong beings that are rooted in the ground and yet moving and adapting when in water. In the works there is a lot of black depicting the ripples, referencing deep emotions of loss and with the tree as a way of thinking about trauma or loss. A lot of my work starts with walks in nature, which is now something that I consider part of my practice.

Water and fluid forms frequently appear in your visual language. How do you interpret the symbolic and material relationship between water and memory in your work?

When I feel anxious, I close my eyes and try to summon a calm state by visualising being held in water, floating. But water is never only comfort, it’s tied to histories of migration and can be unpredictable – soothing, healing, cleansing but also uprooting and overwhelming.

In one of my artworks, Estuary (2024), vivid colours emerge from a deep black reflection. It is an ephemeral moment where two ripples are almost touching, It suggests a brief convergence of fresh and salt waters, echoing a personal and collective longing for liberation “from the river to the sea”. This tension shapes how I think about memory and the desire to preserve and connect, while shifting, erasing and resurfacing become inescapable.

You are currently participating in the travelling exhibition The Lost Paintings: A Prelude to Return, where artists were invited to respond to the lost works of the Palestinian-Lebanese artist, Maroun Tomb. What drew you to this project, and how did you approach the challenge of responding to something that was erased?

This is one of the projects that I was so excited about from day one. I wasn’t sure what exactly I was making, but I was feeling really connected to the premise of the exhibition and points of connection that I have with it when it comes to disappearance. One of the curators, Joëlle Tomb, reached out to me. She is the granddaughter of Maroun Tomb, who held an exhibition in 1947 only for all his work to be lost during the Nakba. I found the history incredibly moving, and it immediately resonated with my own personal experience, particularly the disappearance of my father during the second Gulf War.

I chose the title Under the Oak Tree, from a list of Tomb’s 1947 artwork titles, and began spending time under oak trees during my travels, collecting acorns, reading about oak symbolism and reflecting on its meaning, wisdom, protection and shelter. I wove a new piece on a floor loom and attached it to the back side of an older Jacquard-woven work. That gesture felt important, like uncovering a hidden layer, preserving something from the past while embracing the rebuilding of a space in the present.

How has your understanding of ‘home’ shifted through your practice?

Home is both simple and deeply complex. For me, it’s a feeling more than a place. I’m Palestinian, although I’ve never been there, and because of my refugee status I can’t return. Still, I carry that identity through culture, tradition and memory. It is a unique kind of loss, loving a place you’ve never known. I grew up in Abu Dhabi and lived in Lebanon, which feels most like home to me, but I also find home in other moments – in museums, in my work and in the presence of friends and family. Physical space matters, too. My home is where I create, think and reflect. I’ve lost it twice, once during the Gulf War and again during the Beirut port explosion. These experiences have deeply shaped my relationship with place.

How does your use of materials, particularly textiles, reflect your relationship with the environment?

The tactile nature of fabric resonates deeply with me. For anyone forced to flee, fabric is a portable and precious object – it can be folded, rolled and carried more easily than many other belongings. In Palestinian culture, textiles often carry family history and memory in their creases and embroidered patterns. I also think of textiles as a medium that is intimately connected to the human body. They offer protection and shelter, as with clothing or curtains and walls that create both barriers and entry points, especially when at a larger scale. I like to consider how, in many cultures, textiles can divide or invite into a space while also enveloping us in moments of life from birth to death.

Are there new themes or questions that you feel drawn to explore?

I’m currently continuing my research on the connections that humans have with their environment and its impact on memory and displacement, through creating woven tapestries. I’m also increasingly drawn to the slower, meditative process of hand weaving. It’s a calming experience and one that I want to explore further, especially in relation to colour, material and in expanding my understanding of home.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 120: The Traces Left