Forced into self-imposed exile at a late stage in his life, Maqbool Fida Husain found a permanent and fulfilling home in his adopted country of Qatar.

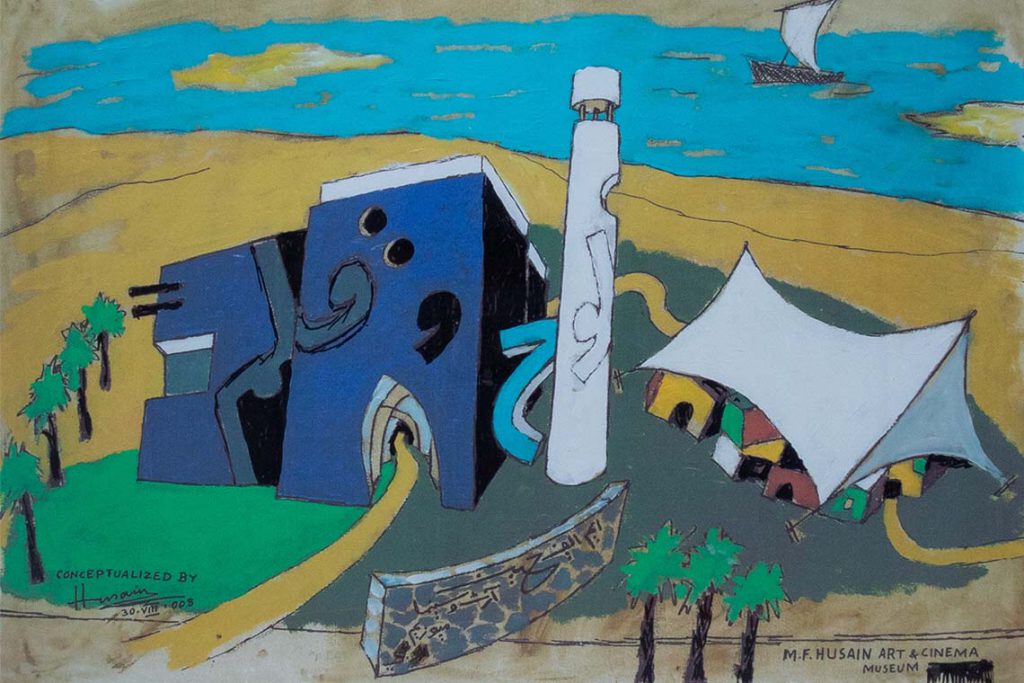

Walking up to the Lawh Wa Qalam: M. F. Husain Museum, set in the heart of Doha’s Education City, feels a little like going down the rabbit hole in Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. Designed by architect Martand Khosla and based on a sketch by the late Maqbool Fida Husain himself, the exterior of the museum is nothing short of fantastical. A blue-toned building made up of tiny fragments of mosaic, it has a white tower on the end and large Arabic script adorning the main facade. There is an animate quality to the building that is also found in the artist’s original sketch, as if at any moment it might start speaking or moving on its own.

One of India’s foremost artists from the twentieth century, Maqbool Fida Husain was known for his Cubist-style narrative paintings and was a founding member of the Bombay Progressive Artists’ Group. The entrance – a double-layered golden door with a yellow-brick road leading visitors inside – is another rather whimsical element, offering a gateway into the world of art and culture that awaits. Qatar is of course is no stranger to iconic architecture, with the world-famous Qatar National Museum and Museum of Islamic Art located nearby. Although smaller in size and scale, Lawh Wa Qalam (meaning canvas or tablet and pen in Arabic) is very much in tune with its larger neighbours.

Founded by Qatar Foundation and inaugurated by Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser, chairperson of Qatar Foundation, the 3000-square-metre museum houses more than 150 of Husain’s works and personal artefacts. Among them are a number of his celebrated paintings from the Arab Civilization series, which he was working on at the time of his death, and the crowning jewel of the museum, Seeroo fi al ardh (2019). The museum is divided into four galleries, each exploring various facets of Husain’s artistic career, with an emphasis on his later years in Qatar. Not limited to any particular medium, he worked across painting, textile, film and photography, examples of which are showcased within the museum’s galleries.

Husain’s continued prominent presence on the Indian art scene was fraught with pushback from Hindu nationalists, critical of what they deemed obscene depictions of Hindu deities, although Husain – from a Muslim family of Yemeni descent – viewed these works as an exploration of the beauty found in other religions. Political pressure culminated in an attack in 1998 by Hindu fundamentalist groups on the artist’s home, with several artworks destroyed. It was not until 2006, however, that Husain would depart India for Qatar, living there in self-imposed exile until his death in 2011 in London, where he used to spend his summers.

Lawh Wa Qalam’s first gallery, A World of His Own, introduces visitors to Husain’s milieu, with a selection of work spanning various media, from an early Cubist style painting entitled Doll’s Wedding (c.1950), or the tapestry The Artist and his Model (c. 1984), to the fascinating Mother Teresa (1998). A depiction of the ultimate matriarch served as an embodiment of the blurred memories that Husain retained of his own mother, who died when he was a child, with the unreliable memory manifested in the faceless figures on the canvas. Also presented are Husain’s paint palettes, paintbrushes and a white smock stained with paint – personal additions which serve to bring the surrounding work to life. Further on is the Film Tower, a small circular room with the highest of ceilings, on which are projected, in ascending height, several of Husain’s films, including Through the Eyes of a Painter (1967), Meenaxi: Tale of 3 Cities (2004) and Gaja Gamini (2000).

The second gallery, A Curious Mind, sits almost in defiance of the reasons why Husain ended up in exile. Here, the artist is shown as having been on an “enduring quest for unity and diversity” in his exploration of faith and philosophy, as outlined in a text at the section’s entrance. Rather than seeing religion and faith as dividers, as the political groups which forced him into exile did, he viewed them as unifying forces and attempted to find common symbols and languages that could break down the boundaries between cultures and belief systems. His Theorama series sought to unify disparate faiths through these symbols, with each frame depicting a different system of belief, such as the cool-toned Christianity and the colourful Sikhism (both 2003).

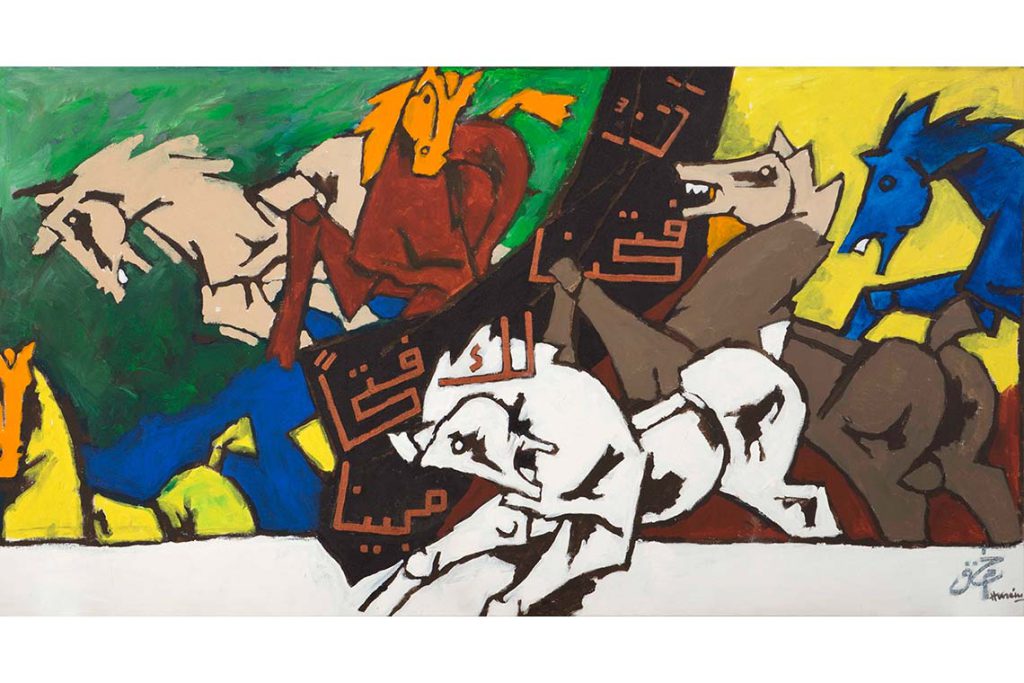

Husain’s world is explored further in the third gallery, An Artist Without Borders, which looks particularly at his quest to reconnect with his Yemeni roots and delve further into the Arab world. Visitors are invited to discover the famed Arab Civilization, commissioned as a series of 99 pieces by Sheikha Moza bint Nasser but with only 30 realised before the artist’s death. Each canvas blends traditional Arabic script with Husain’s modernist aesthetic, while important Islamic narratives appear in The Battle of Badr and traditions of Christian and Muslim faiths meet in The Last Supper of the Desert. Horses – and Husain’s enduring fascination with these animals – are given a prominent place in this section, not least for their important pictorial role in the works from Arab Civilization. Under Husain’s hand, and most especially during his later years in Qatar, the horse became an emblem of everything that the artist sought to coalesce in his art – “For Husain, the horse was never merely an animal. It was a symbol, capturing the essence of history, faith, and myth,” reads a gallery text.

The last gallery is named Seeroo fi al ardh after the eponymous large-scale multimedia installation that fills the space. Husain’s final work and part of his project on Arab civilisation, it was completed by Qatar Foundation after his death. In a 20-minute-long activated display, the story is told of mankind’s progress and innovative spirit while making use of the resources available on land, in sea and in air. The kinetic carousel installation which forms the bulk of the installation features five horses made from Murano glass, with a bronze sculpture overhead and five vintage cars, while music plays and images of Husain’s work are projected behind the revolving sculptures.

Standing as a symbol of the museum’s wider mission to capture the spirit of artistic endeavour, Seeroo fi al ardh honours the past while looking towards the future and always seeking to unify. By offering a space for discovery through its galleries, and for learning through its library space, the Lawh Wa Qalam Museum strikes a perfect balance – while being imbued with a certain amount of magic – as the forever home and abiding legacy of Maqbool Fida Husain’s creativity and achievements.