At the sixth Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the fleeting present is grasped through poignant works that elevate unseen voices, global uncertainty and the fight for resolution.

Off a busy road in the historic neighbourhood of Mattancherry in India’s coastal city of Kochi, a rising garden of tropical plants from the surrounding Kerala countryside provides moments of solace and transcendence. A gentle maze-like pathway guides visitors through derelict structures behind 111 Markaz & Cafe, where Belgium-based artist Otobong Nkanga’s gardens Soft Offerings to Scorched Lands and the Brokenhearted (2025) are growing under the continuous care of local gardeners for the latest edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale. Leading to a small pond, around which is seating moulded out of mud and laterite and covered with locally woven mats of cane and bamboo, the works invite visitors to pause as a soundscape plays and contemplate the interconnectedness of human bodies to the natural bodies of water and vegetation, the cycle of life and the process of regeneration. At the start of the biennale, which opened on 12 December, most of the plants were in a nascent stage. By the time the event culminates at the end of March, the plants in Nkanga’s gardens are expected to have fully blossomed.

The intimate, innate and fragile bonds between the land, human beings and the ephemeral cycle of life found in Nkanga’s gardens are common to the works in the biennale, which is entitled For the Time Being and curated by Nikhil Chopra and Goa-based artist-run collective HH Art Spaces, of which Chopra is co-founder. Prior to the calming, contemplative experience of Nkanga’s gardens, the visitor must pass through 111 Markaz & Cafe, where they first confront Black Gold (2025), an installation by Dhaka-based Yasmin Jahan Nupur and made from colonially exploited materials of muslin, silk and jamdani, with embroidered maps highlighting the Western construct of the Silk Road. Reflecting the historic trade in black pepper, once known as black gold and a primary driver for the Age of Exploration, Nupur demonstrates how its colonial impact continues to influence the present.

The fantastical hybrid creatures of Congolese-born, Berlin- and Oslo-based artist Sandra Mujinga’s sculptural installation Remember Me (2025) emerge in the next room. Revealing two large anamorphic forms, their gently curved metal bodies were welded locally and are draped in dark fishing nets sourced by the artist in the markets of Kochi. Reflecting Mujinga’s interest in ancestral crafts, namely the basket-weaving traditions of the fishing community of Chutes Wagenia in the Democratic Republic of Congo, her enigmatic creatures cleverly metamorphosise and replicate, with their heads also serving as tails. “My work investigates ways of hiding and concealment,” says the artist. “The fishing nets provide transparency, but also gestures of opacity.”

The biennale features work by 66 artists and collectives from over 25 countries, presented across 29 venues throughout Kochi. “We are all connected by love,” said Chopra during his opening address at Aspinwall House. Connection – whether physical, spiritual or ecological – is a key element to the works displayed. While they wrestle with the deep uncertainty of the present and the pain of the past, artists bravely confront personal and collective vulnerability to tackle present challenges with tinges of transcendent ephemerality. Chopra is known for his performance work and has commissioned some of the medium’s biggest names. The event kicked off with a performance of traditional Chenda drums and percussion by Margi Rahitha Krishnadas and her team, followed by A New Alphabet by Monica de Miranda and Procession for a Shifting Storm by Singaporean-born Zarina Muhammad, exploring loss, resistance and regeneration in South Asia. On 10 February, Marina Abramović will give a lecture performance.

The fight for social justice and elevating the voices of the unseen is a particularly strong thread. At Anand Warehouse, a striking installation by Prabhakar Kamble seeks to address the existential conditioning of India’s silent majority, continuously marginalised by the hierarchies of the country’s ancient caste system. Entitled Vichitra Natak (Theatre of the Absurd) (2025), a gravestone with the phrase “Annihilation of caste” is placed in the middle of a pile of soil, out of which rises a sculptural theatre of various moving parts from found and fabricated elements. The cacophony of sights and sounds offers to reclaim forms often dismissed as folk art and to dismiss ideas of caste in favour of ethics based around skill and camaraderie.

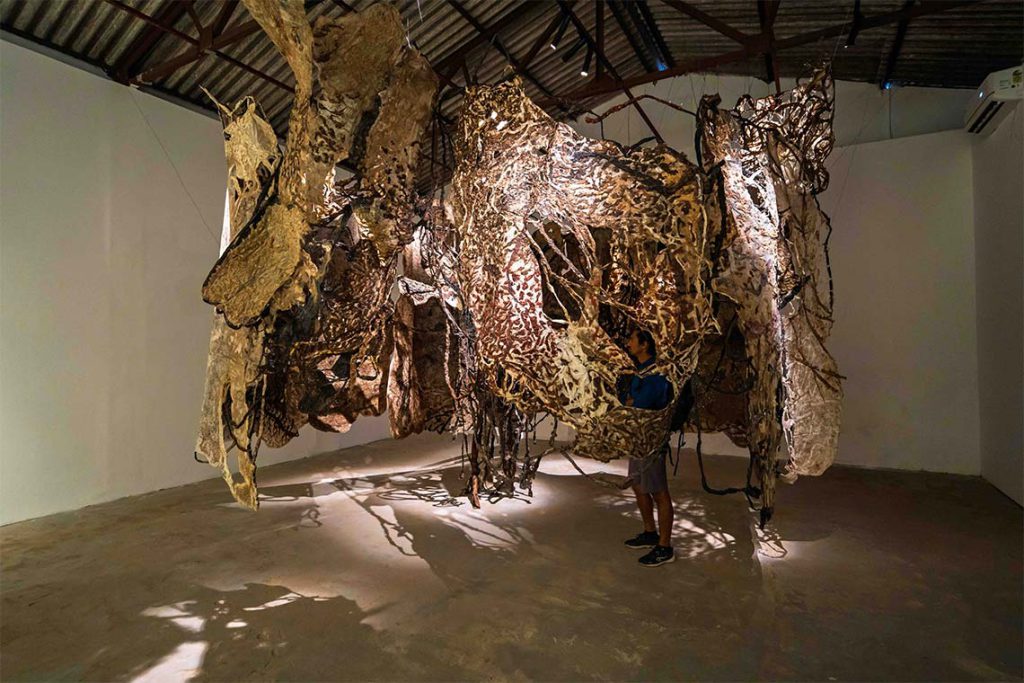

Kamble’s humorous yet insightful piece is followed by Ibrahim Mahama’s iteration of his ongoing 2017 work, Parliament of Ghosts. In what makes for a poignant sight, Mahama has placed a wall-sized tapestry of sacks sewn together by female homemakers in conversation with rows of rickety chairs stabilised for use by carpenters from Kochi around the space. Here, Mahama explores forms of labour in India while breathing new life into mundane objects. In an adjacent room, Kolkata-based Jayashree Chakravarty’s installation Shelter: for the time being (2025) reveals long suspended scrolls stitched together to form a seeming protective cocoon or a realm that has been narrated by non-human creatures.

“Molds without a name is discarded as waste, then what of the laborers whose name was never discarded?” reads a terracotta plaque in Indian Birender Yadav’s installation in Aspinwall House. Only the Earth Knows their Labor (2025) reconstructs the ambiance and structures of a kiln without workers, where only the results of their labour remain. Nearby, an evocative series of copper plates in captivating hues of turquoise, entitled Chronicles and by Kirtika Kain, explores the volatility of time through layers of peeling and crusting patina. It refers, explains Kain, to India’s Dalit community, the lowest order in India’s caste system. The markings in Kain’s works serve as a metaphor for undocumented Dalit histories, which persist by being passed on and embodied through memory and the earth. In Biraaj Dodiya’s DOOM ORGAN (2025), a series of painted steel sculptures and paintings alluding to the silence of a mortuary is charged with a poetic sense of pain. Inspired by the 1341 CE deluge that ruined the ancient port city of Muziris and birthed Kochi, the installation simultaneously refers to the constant stream of violent images that appear on our phones through social media.

While the curation of works flows organically and performatively through Kochi’s various spaces, interacting with the urban and historical fabric of the city, undertones of distress are whispered. Since the biennale’s inaugural show in 2012, the partially state-funded event, considered India’s most prominent showing of contemporary art, has struggled with logistics. These problems came to a head during the last edition, of which the opening was postponed for 11 days. While these issues persist, with some works not fully installed for the opening weekend this time around, the biennale offers a powerful artistic call to confront the current world’s violence, heartbreak and displacement – all of which is intertwined through the works with a profound desire for meaning and fleeting moments of transcendence. Such a yearning to seize and ground oneself in the ephemeral present begs the question: can slivers of momentary resolution for the time being inspire long-term personal and collective transformation?

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale runs until 31 March

This review first appeared in Canvas 121: If Walls Could Talk