While largely a seed for future conversations, Resonant Histories: India and the Arab World is a refreshing and overdue exploration of the ties between Indian and Arab modernisms.

The Arab world and Indian subcontinent share a vast web of kinship. From food and dialects to crafts, customs and more, the flows of people, ideas and commodities between these regions – at once unequal, brutal, profitable, creative – are still understudied compared to Eurocentric discourses. However, with diminishing interest in Western-oriented aspirations, economies and aesthetics, a shift is now apparent. Contemporary biennials and art markets in the Arab, South Asian and, most recently, Central Asian regions have begun to flourish in the past few years, and artists and cultural workers from these places are engaging in increasing dialogue and exchange. Curatorial and critical focus on this dimension is not just relevant now, it is overdue.

In Mumbai, the Jehangir Nicholson Art Foundation (JNAF) and Barjeel Art Foundation (BAF) in Sharjah have collaborated for Resonant Histories: India and the Arab World, a richly stacked group show at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS), where JNAF is based. The idea first arose during an encounter between BAF’s director Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi – whose own father grew up in Bombay – and Dr Sabyasachi Mukherjee, director general at CSMVS. Curated by Puja Vaish and Suheyla Takesh, the exhibition aims to present the linkages between Indian and Arab modernisms as a starting point for further South-South/East-East research and discourse.

In order to fill an art historical lacuna, the show tries to be both a conversation-starter and extensive, thereby suffering from feeling not quite enough and rather too much. With works from India, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia and the UAE, the wider scope of India’s neighbouring countries and diaspora is discounted, while histories of multiple countries are collapsed into one Arab ‘world’. While not so dire an outcome, it makes for an unwieldy tension that is hard to shake off, especially as the seven section texts (already overabundant for this one gallery space) dart between so many different artists, works and ideas, scattering audience focus.

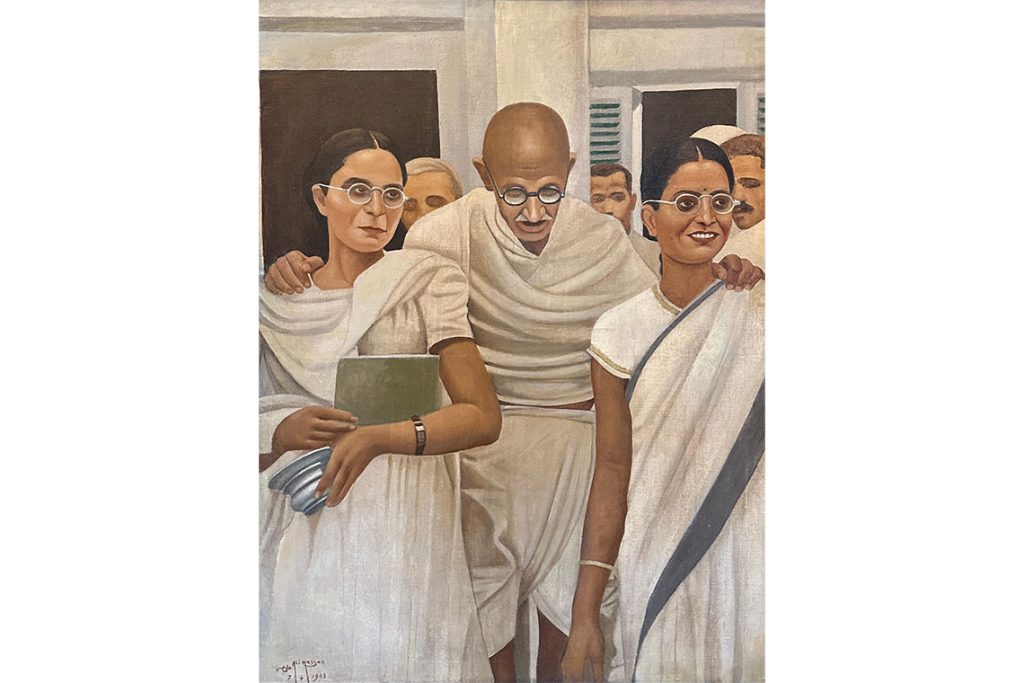

Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah

The exhibition’s most powerful takeaway is how the displayed resonances between these regions become what one might call “resonances across time”. What inspiration and fuel can be sourced today from those Indian and Arab artists who shared ideas, problems and methods during the era of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), an anti-colonial bloc of transnational solidarities? All at a time when India did not just formally recognise the state of Palestine but also actively supported its freedom struggle, once linking Palestinian self-determination with its own fight against imperialism – starkly contrasting with India’s current allyship with Israel.

With its title in English, Arabic and Hindi, Resonant Histories opens beautifully with Mona Hatoum’s Bukhara (red) (2007), which depicts a world map on a dark red traditional Persian rug. Except that Hatoum’s view of the world – and thus, ours – is altered. Instead of the standardised Mercator projection of the map most of us see, she accurately rescales it using the Gall-Peters projection, demonstrating how the Southern Hemisphere is actually nearly double the size of the Northern. The map is also faded white, the ‘truth’ of the world rendered a haunted spectre. This cartographic course correction serves as a firm, poetic start.

The first section, Visions of Freedom, foregrounds shared liberation struggles in the twentieth century. Egyptian artist Ali Hassan’s Untitled (1948) is a stunning portrait of Mahatma Gandhi flanked by two of his female followers, made in tribute to him shortly after his assassination. An Akbar Padamsee work also depicts the leader. These are shown alongside Syrian artist Said Tahsin’s Nation and Leader (1962), a more complex, large-scale portrait of former Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, against a backdrop of people from various countries that were part of the NAM. Although it would be crude to draw an equivalence, and while recognising that every leadership is nuanced, a close contemporary reference to such a scene would be images of Zohran Mamdani’s recent election as the mayor of New York – which have been so galvanising for many.

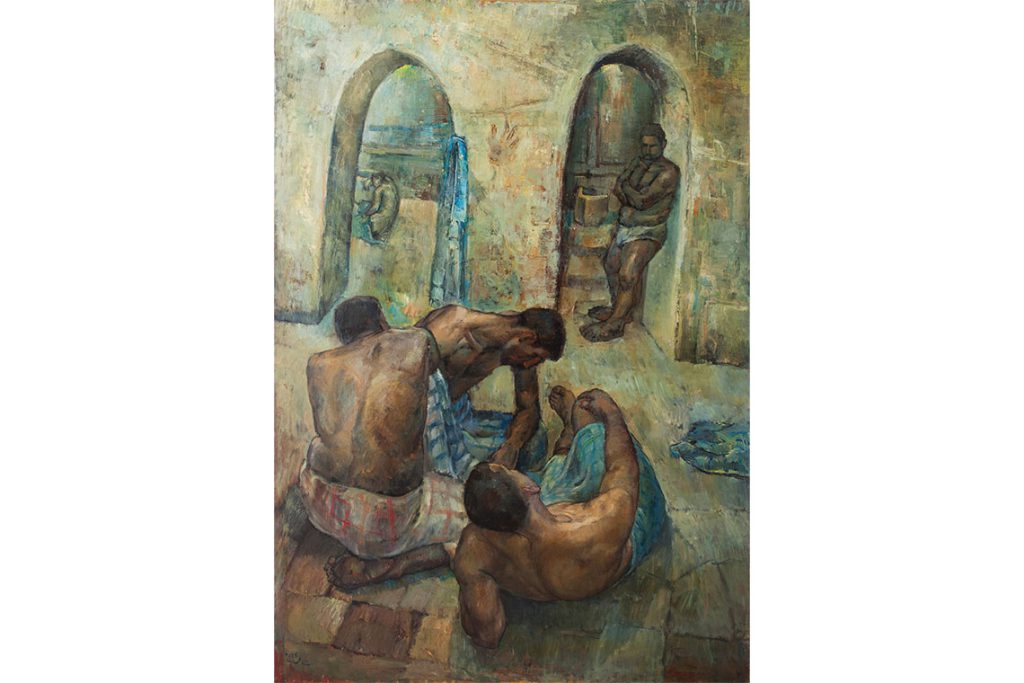

Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah

The bold, black-and-white keffiyehs in Naim Ismail’s Al Fiddaiyoun (1969) are complemented with works by Chittaprosad, a self-taught, anti-caste artist and former member of India’s Communist Party. His etching-like prints are genuinely arresting documentations of the colonially manufactured Bengal Famine. This section, as full as it is, only brims further: Vivan Sundaram’s Eclipse (1991) is an incredible material critique of the 1990 Gulf War using charcoal and engine oil. Krishen Khanna (who was raised in present-day Pakistan and recently turned 100 in New Delhi) mixes mourning and melancholic military green oils to address the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war. Nilima Sheikh’s My Hometown (2009) is a paean for the double consciousness of Kashmir, while Tyeb Mehta’s Untitled (1971) shows a literally partitioned canvas and body.

One could have constructed a separate, perhaps more focused, exhibition solely from Visons of Freedom alone. This could include works from Resonant Histories’ other outstanding section, Between Labour and Leisure, specifically a remarkable triple-pairing: Ahmad Nasha’at Al Zuaby’s The Bathers (1984), Mohammed Kazem’s Windows (2019) and Sudhir Patwardhan’s Bhaiya (1999). In all, working men are seen in private domestic spaces, taking care of themselves, even, and especially, when their society and state do not. Bhaiya is resonant for the Mumbai outside this gallery, mired in extreme social inequality. Windows offers both relief then discomfort – relief that, in a show produced by Indian and Emirati institutions, there is representation of the unequal labour migration between these countries. At the same time the viewer notices this, it also becomes insufficient to hold in one seven-year-old painting alone.

Elsewhere, we do get the influence of Indian zari fabrics, popular in the Gulf, in Emirati artist Najat Maki’s Sunrise (circa 2000s) – even if it is abstract. In fact, one could extrapolate another offshoot exhibition just on Indo-Arab craft and textiles, an idea bolstered by the work of Kuwaiti artist Jafar Islah, who spent a significant amount of time learning from local Indian artists and craftsmen. The aim of Resonant Histories to spark off new research questions clearly succeeds here.

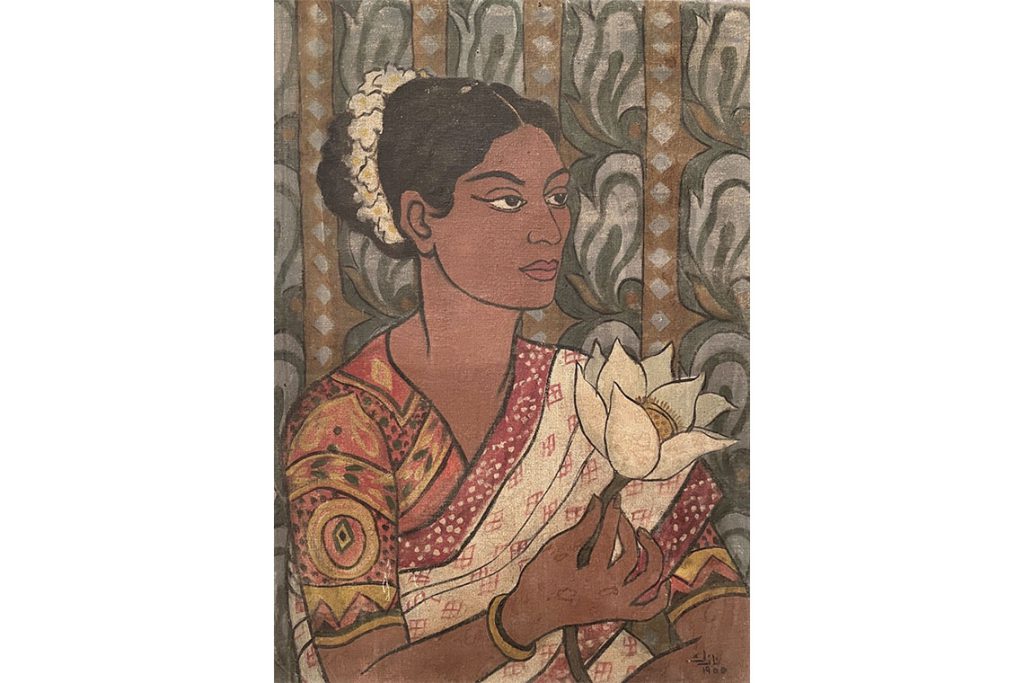

Collection of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah

Other sections, which traverse from materials and abstraction to landscapes, urban space, architecture and ‘Inner Worlds’, sometimes feel a bit more tenuous, even if they are filled with mammoth artists, precious discoveries (for instance, learning that Indian rupees were once accepted currency in Bahrain) and individual or unexpected gems. One of these is The Lotus Flower (The Lotus Girl) (1955) by Nazek Hamdi. The Egyptian painter travelled on a government scholarship to India in the 1950s, where she obtained degrees from the Universities of Tagore and Rajasthan and trained at Santiniketan, an artistic and educational hub that plays a huge role in the history of Indian modern art. Hamdi’s portrait is of a breathtaking Indian woman in a patterned sari, with distinctly localised patterns and fluid black lines like kohl. It is a real pièce de résistance.

A large number of the 67 artists in this show participated in the India Triennales, which ran for 11 editions from 1968, at about the zenith of the NAM. One of the Triennale’s main goals was to position India as a major artistic centre beyond the Western- and Soviet-led blocs and nurture a decolonial internationalism, particularly among newly independent nations. In Resonant Histories, we actually get to see a work exhibited at the Triennale’s first edition: Emirati artist Abdul Qader Al Rais’s Waiting (circa 1970), a painting of four Palestinian refugees in Kuwait following the 1967 Naksa.

Somehow, a whole constellation of histories rests within this one painting, displayed in this specific show. Our contemporary global politics are so different and so grim that such serendipities and solidarities feel like snatches of lost glitter. But a true bravo to the teams that have found and curated them – they open the door for us to find and build even more.

Resonant Histories: India and the Arab World runs until 15 February