The Saudi-born artist reveals how her architectural background and cultural heritage inform her interest in domestic interiors, exterior spaces and the places in-between.

Canvas: What influence does architecture have on your artistic creativity?

Hayfa Algwaiz: During my eight years practising architecture in San Francisco, I participated in several global biennials with my part-time work doing academic architectural installation. I realised my interest lay in visual storytelling, especially for underrepresented architectures like Khaliji spaces. Coming home to Saudi Arabia, I would always notice design decisions that make sense for the culture, whether the layout, materiality, divisions of space, circulation or access to areas. Space holds stories, it can show who someone is. There’s a beautiful nuance in capturing these seemingly banal yet defining objects and materials.

There’s often a tension in your work between the traditional and the modern, interior and exterior spaces, such as in Waiting Room (2025) and Al Balad Residences series (2024).

My practice looks at these two worlds, the interior and the exterior, and how they tend to reflect and mirror one another. There is the home and the activities that happen there, the urban environment, and the threshold where these two meet, such as windows and doors. Those paintings are a way of grappling with the tension between public and private, being seen, being invisible. The work is very personal. Most of these places are in Saudi Arabia, unless I’ve done them in a residency abroad. Each painting is a real place taken from a photograph of mine, rendered in a photorealistic style, although there is sometimes an incompleteness where I expose my process to the viewer, which is more intimate for them.

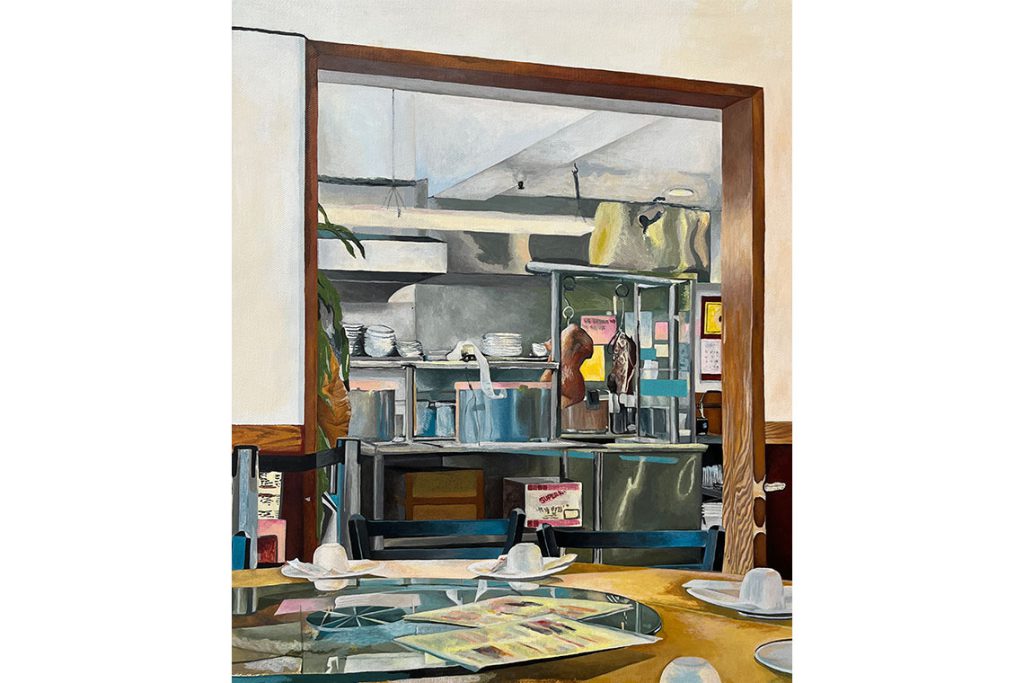

A piece of meat or a woman’s body (2024) features a restaurant. Could you tell us more about this space?

The setting is a Chinese restaurant in Oakland, California. I took a photograph of this piece of meat hanging up, which looked eerily like a woman’s bust. Growing up, I’d hear men catcalling women using the term Ya lahma, which was comparing them with a piece of meat. This reminded me of that reference and of the anxiety of being a woman and being perceived, being objectified, for consumption. The colours of the painting are so delicious, bright and vibrant, like a candy store.

How does cultural context tie into the liminal spaces you mention?

The Al Balad Residences series is me looking at Al Balad from the outside, from pictures of window screens, of different architectures and layers of history, and then collaging them. My work often questions access, visibility and understanding. I was looking here at ornament and how I’ve found that in the West it can be seen as backwards, whereas in our context we see it, or I do, as a symbol of safety – whether on gates, windows, railings, stairways or on the body. The point of view from which I take the picture is crucial, because it signals whether I have access to it or not, and how. This relates to my domestic scenes, which are usually in my own house.

Is there an element of controlling access to these intimate spaces?

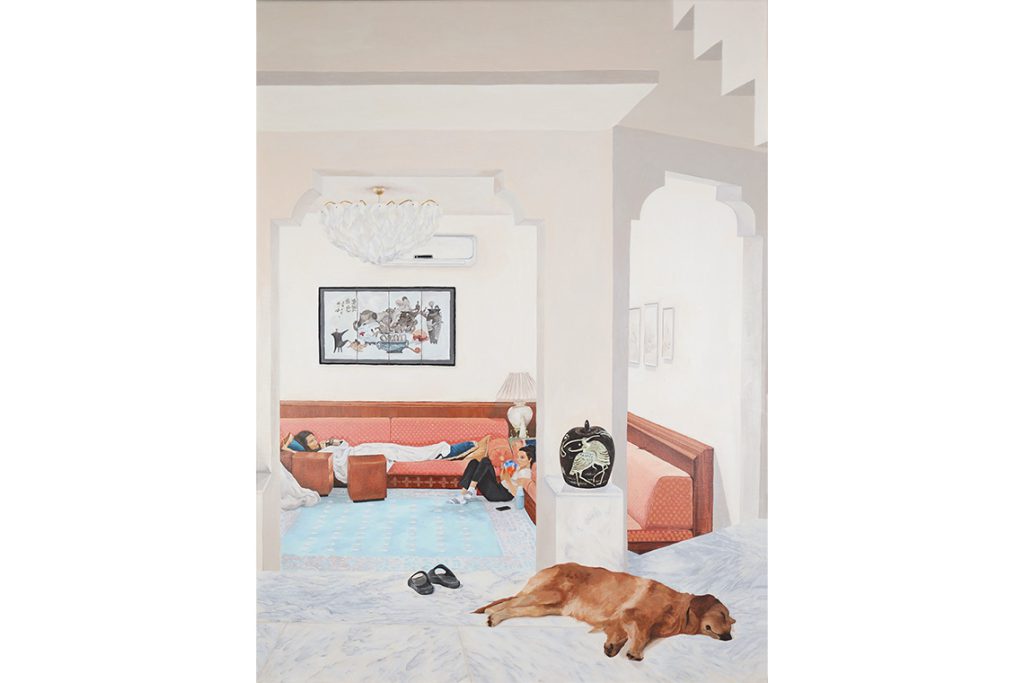

Absolutely, it is about me reclaiming the power and taking the narrative into my own hands – although most of my domestic paintings don’t have people in them. The Living Room (2022), which was the first painting I made when I decided to become an artist, wasn’t meant to be seen by anyone or displayed, because my sisters are in it. During my first institutional show, I started thinking about how to tell my story without stripping my family of their privacy, which led me to the Abaya series.

The abaya is such an interesting object. It is intrinsically tied to the house, as it covers the woman when she is outside of it, and the house is the only place where it can be removed. The paintings depict this intimate moment of release when this second skin comes off. An abaya on its own holds so much tension and personality. I know who’s home just by seeing whose abaya is hanging up, or on a chair or on the floor. For us, it has such a different meaning from what it does for the rest of the world. The depiction of people is something I would really like to challenge myself with going forward, maybe by developing techniques for abstracting the figure.

Would you consider other ways of depicting these domestic spaces, as in different media?

I showed a video project in the Saudi Pavilion at Expo Osaka about the perception and memory of intimate spaces. I turned hand sketches drawn from memory of my childhood home into a 3D model of the house. There were a lot of mistakes, which I incorporated into the work. The video component looks at how light travels in the Saudi domestic space. Light has such a specific shape in each context. In my house, it is so dappled through these screens. This was accompanied by scroll paintings on upholstery fabrics. Video is an interesting medium, as each shot is like a painting in motion. At the moment, I am working on a series for my residency in Accra, where I am exploring larger-scale work, which is also an element I would like to explore further.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 121: If Walls Could Talk