Tala Madani sends waves of toxic masculinity across a dystopian dancefloor in her solo show Shitty Disco at EMΣT in Athens.

With women’s rights ever under threat, the question of gender equality and how this might look has prompted the National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMΣT) in Athens to mount a series of exhibitions encouraging women and female-identifying artists to consider alternative visions. Invited to respond to the cue ‘What if Women Ruled the World?’ the goal of amplifying the female experience or addressing skewed power relations is understandably of concern to the participating artists.

According to EMΣT’s artistic director, Katerina Gregos, such programming invites reflection on a redistribution of power and alternatives to the dominant patriarchal paradigm, which appears to be steering the world towards war-induced destruction. Tala Madani turns this task on its head. Her current solo presentation at the museum, Shitty Disco, negates the female form, instead imposing upon her audience a perverse and grotesque universe inhabited almost exclusively by men. Produced over more than a decade, the exhibition features 50 works – oil-on-linen paintings and stop-motion animations – that contribute to Madani’s illusory nightclub.

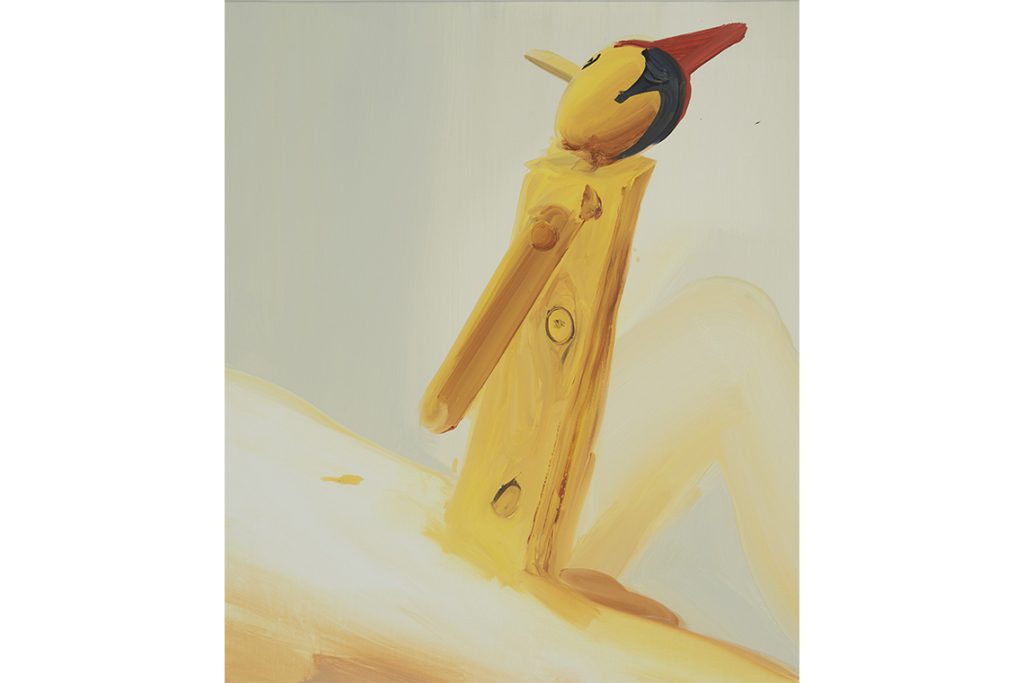

The artist has never shied away from the obscene or alarming. Through her blend of satire, carnivalesque subversion and playful simplicity, Madani’s compositions – reminiscent of the concerns of Paula Rego and James Ensor – usher the audience in while hacking away at accepted norms and inner anxieties. Shitty Disco is the kind of nightclub that most would rather avoid, populated by a litany of male archetypes that includes politicians, performers, hunters, man-children and prisoners as exemplified in paintings such as Pinocchio Plank (2021) and Front Projection (Horned) (2016). Her male figures are rapidly rendered, white, balding and bloated. They embody a child-like, cartoonish quality and their behaviour is vulgar. They are vomiting, urinating or smearing shit, yet Madani’s skilful modulation of colour and amplification of scale lends her scenes an aura of the divine.

The exhibition’s title, derived from one of the works on display, evokes the disillusionment of an evening misspent at a dodgy nightclub, a cavern where feverish fantasy and humanity’s worst traits collide. Men are depicted shirtless, suited, in striped pyjamas or in trucker caps. They are either solitary, glowing under spotlight, or en masse, evoking a sense of fraternity, ritual and herd mentality. They engage in various primal activities – crawling, unleashing bodily fluids on one another, or illuminating the disco floor with beams of light emanating from their assholes. The domination of the male form upon the exhibition walls is a rejoinder to the historical representation of the passive and sexualised female under the male gaze. Madani amplifies the current climate of toxic masculinity in the West, urging viewers to consider it within a broader social, political and historical context.

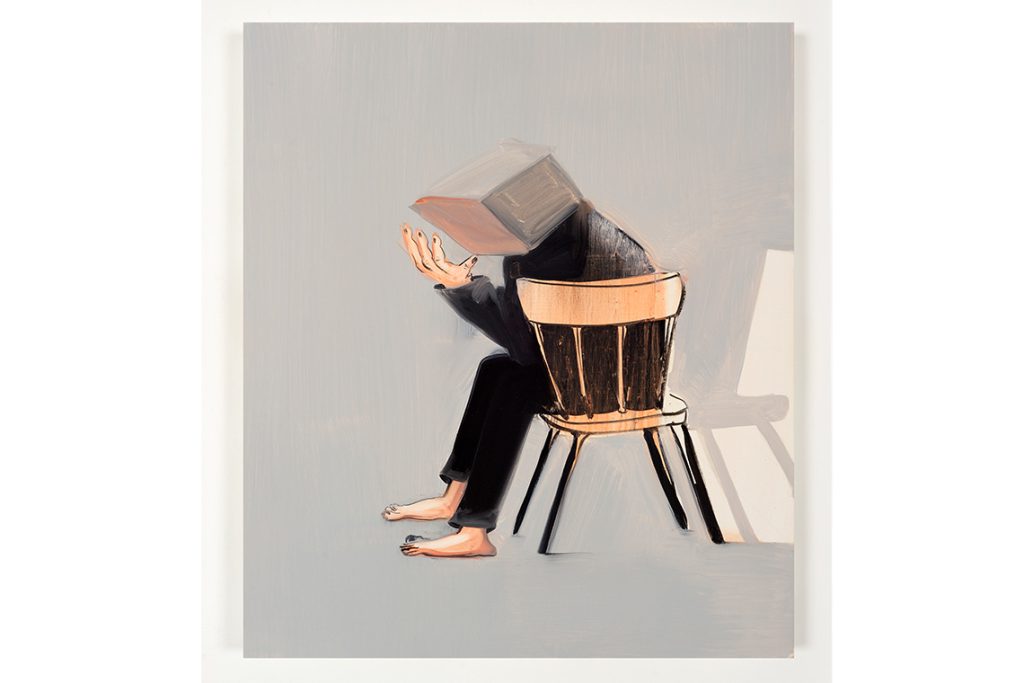

The level of shock is mediated by a quirkiness that allows Madani to raise taboos relating to childhood, sexuality and violence that might otherwise spark outcry. Despite the comedic relief on offer, Madani’s paintings are complex and multilayered. Beyond her engagement with a triangle of power, gender and politics, we are led to reflect upon the role that media and technology play in manipulating our consciousness. Devices such as flashlights and computer screens are violently rammed into the human body. Madani shines a light on men removing their social masks, choking on their microphones or performing on stage. The imposition of artificial light in several of the scenes emphasises the performative and constructed character of our social world, suggesting disillusionment with present-day political discourse and media narratives.

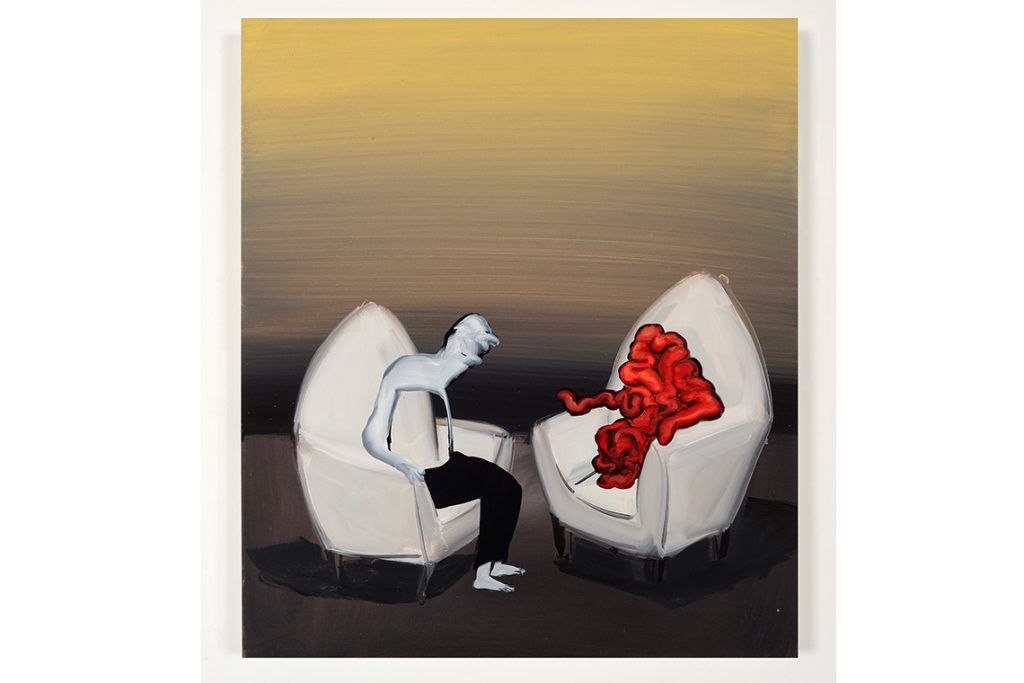

The projector, a recurring Madani icon, signifies amplification and propagation as well as an awareness of the audience. Projections facing outwards symbolise life, creativity and desire, while the ‘rear projections’ that radiate from men’s bottoms express themes of death, digestion and endings. Madani’s manipulation of scale – works range from 40 cm to over four metres – mounts tension in the exhibition space, as viewers zoom in and out of her narratives. Her central figures are often enveloped in empty space, with pieces like Boxed Head (2011) and Guts (2011) recalling the codes of Francis Bacon. Seated figures appear both suffocated by the domestic setting and suspended in the void.

At the centre of the room, five screens play Madani’s stop-motion animations, which she has been producing since 2007. Each animation, composed of approximately 2500 still images painted onto wood using thick, impasto layers, is recorded frame by frame. The medium’s imprecision lends life to her clumsy protagonists and allows narratives from her two-dimensional works to flow and merge with the onscreen visions. In Music Man (2009), a man uses the white fluid emitted from another man’s bald head to notate a musical score. Next to it, The Womb (2019) situates the surrounding fellows within our contemporary dystopian reality. In the film, a growing foetus in its fleshy sanctuary observes a flashing synopsis of human history underpinned by violence, technology, media, and medicalisation. As the foetus reaches its final stages, ready to enter the world, it becomes armed with its own baby-sized gun. The screens are set between four imposing columns adorned with fresh site-specific wall paintings. Strips of film reels wrap around them, suggesting the artificiality of life which mirrors cinema. They form a connective thread between Madani’s on-screen animations and the surrounding two-dimensional paintings.

Exceptions to Madani’s male-dominated domain include two works from the ethereal Cloud Mommies (2022-23) series. Here, the mother, her breasts drooping, hovers over us all, imagined as a cloud upon two monumental blue-and-white canvases. For the first eight years of her artistic career, Madani only painted men, then in 2019 she began her Shit Moms series spurred by her own transition into motherhood. Rooted in the Western cultural anxiety she observed surrounding parenthood, the series questions the visual identity of mothers in art history, who are often depicted as iconic, sacred and virginal. Cloud Mommies continues this critique, yet the mother has evolved from a figure formed out of faeces to that of a cloud. Childlike drawings etched into the bottom of the canvas remind us of mommy’s former reality, bridging generations and alluding to the passage of time. Madani might be suggesting that, despite everything, the mother remains in the backdrop of everything, the life source contributing to our self-perception and the person we talk to our therapist about. Alternatively, she might be depicting the ultimate “shit mom”, one overwhelmed by a grotesque world defined by men and who has committed the ultimate betrayal to her child by taking her own life.