The Only Way Out Is Through, the 20th anniversary show of Dubai mainstay gallery The Third Line, is a chance to reflect on how the city’s art scene was built – and where it might go next.

Recently, in a friend’s car near Bur Dubai, I snapped a picture on my phone at a red light. It captured a white mosque against a hot blue sky, a likely imported heritage ship monument beside it, a Ferrari to the left, a Careem taxi in the foreground and a delivery rider in thick head-to-toe garments ahead. Large, hulking traffic lights formed a frame, cameras potentially hidden inside. I smiled. So much of the city I had grown up aspiring to – my parents nursed a Gulf Dream, instead of the crumbling American one – and its contradictions, appeared together here. I found the image beautiful because I could understand it – the relief of familiarity, an ungovernable belonging.

Derided, dismissed, devoted to, danced in – yet never ignored – Dubai “represents an unsettling post-western horizon,” wrote Momtaza Mehri in a recent Guardian article. “A version of the future that is already here.” It wasn’t always like this. Two decades ago, an ‘art scene’ here was more an idea. A little more than three decades before that, this was not yet a nation. The evening of the car photo, I sweated through the overcrowded metro to Alserkal Avenue for the exhibition opening of The Only Way Out is Through: The Twentieth Line. Curated by Shumon Basar, the show celebrates 20 years since the opening of The Third Line, one of the UAE’s first galleries and among the most pivotal in terms of shaping an art industry that now beats as furiously as an overactive heart.

When co-founders Sunny Rahbar, Claudia Cellini and Omar Ghobash first registered The Third Line in a warehouse space in 2005, they were countering life in a post-9/11 world, infected with rising Islamophobia and anti-Arab sentiment. MENA art was not just overlooked but newly imbued with dangerous prejudice. The year prior, Rahbar and friend Lisa Farjam had founded Bidoun (Arabic and Farsi for ‘without’, often meaning without a home or state), an arts and culture publication that eschewed restrictive definitions of the Middle East and its diasporas. This further paved the way for the gallery’s founding. Bidoun admirably balanced serious enquiry with a humorous, avant-garde edge (a multi-artist interview was deliciously titled Hash is a Vegetable), and you can see that editorial punch in some of The Third Line’s older exhibition titles: I Saved My Belly Dancer. Water Panics in the Sea. What Happened to My Dreams?

Whereas “the West has [had] a habit of hoarding complexity for itself,” Mehri writes, Bidoun put forward a new cosmopolitanism with fluid geographic centres. Now, we trace how The Third Line has attempted to do likewise. The Only Way Out Is Through presents 74 works, many of which have not been seen before. Every single one of the 31 artists on the gallery’s roster is represented. Accompanying the artworks are slick posters (very reminiscent of Jameel Art Centre’s 2021 show Age of You, co-curated by Basar, Douglas Coupland and Hans Ulrich Obrist) presenting visualised archival data, like the nationality breakdown of the artists. About a quarter are Iranian and nearly 20 per cent American. Sociopolitically, given how the world has changed, I am curious how this might, and maybe should, change in the next two decades; selfishly, I hope the South Asian representation goes beyond Rana Begum. Or what connections could be made with South East Asia and Africa?

Meanwhile, the gallery’s historic impact cannot be understated. The Third Line was among the first galleries from the Middle East to begin consistently participating in international art fairs like the Armory Show, Art Basel and Frieze. It normalised, to the dominant Western gaze, the appearance of artists from this region in blue-chip contexts, presenting them as conceptually rigorous, contemporary and sophisticated in their own right. This led to their work being acquired and collected more overseas, garnering both critical and market attention. Consequently, perceptions started to shift slowly away from tokenising, novelty and ethnographic lenses – the significance of which younger generations might risk taking for granted, when those same Western fairs and institutions are now flocking to this region.

The Third Line is not a stalwart simply because of diversity achievements. Its roster has always been especially cool, a binder full of distinctive and prolific heavyweights, many of whom have grown with the gallery since their early days, like Hassan Hajjaj, Lamya Gargash and Abbas Akhavan. The thrill of encountering yasiin bey (rapper Mos Def) and Spanish-Moroccan painter Anuar Khalifi’s work together in a space, for instance – as I did a few years ago in Negus – is replicated multiply within The Only Way Out Is Through, even if at varied volumes. The exhibition is at its strongest when it elicits that click of familiarity within viewers with whom it shares a city, a country, a region or a language.

Shirin Aliabadi’s Girls in a Car (2005) turns a camera flash into a spotlight on young girls from the Iranian urban middle class during a traffic jam, made up for a night out. It subverts the paparazzi images we are used to seeing of young Western female celebrities having their fun. It is also a portrait of a time, one that resonates anew in the context of the recent Woman, Life, Freedom protests in Iran. Egyptian artist Huda Lutfi’s Lipstick and Mustache (2010) comprises two sculptural busts modelled off her own head; one masculine, one feminine, both wearing sunglasses with lenses that have been replaced with images of soldiers. The work is playful yet snarkily referential to gender politics and military and state power. Hayv Kahraman’s paintings are ever-strong and it is a treat to discover some of her earlier work, particularly its influences from Japanese woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e). There are those who we have recently lost –– the magnificent Tarek Al-Ghoussein, Farhad Moshiri and Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who have classic works exemplifying their singular practices, as if to say: these giants were here.

You cannot miss Changing Room (2019) as anything but a Farah Al Qasimi image, a group of Arab American women in vibrant hijabs helping their pageant queen get her makeup just right. One shines her cellphone torchlight from above, like something godly. There is sacrality in their caretaking of their beauty, its pomp and simultaneous intimacy. The more surprising finds are Al Qasimi’s older images, which tease out the quirks and artifice of UAE cityscapes’ past lives, like the fantastical contrasts of Abu Dhabi’s architecture in Sandcastles (2014). Or the ghost of a giant McDonald’s ‘M’– that lingering spectre of fast delivery philosophies embedded in living here. It is a language that much of this show’s audience will understand, like a joke landing in a familiar tongue.

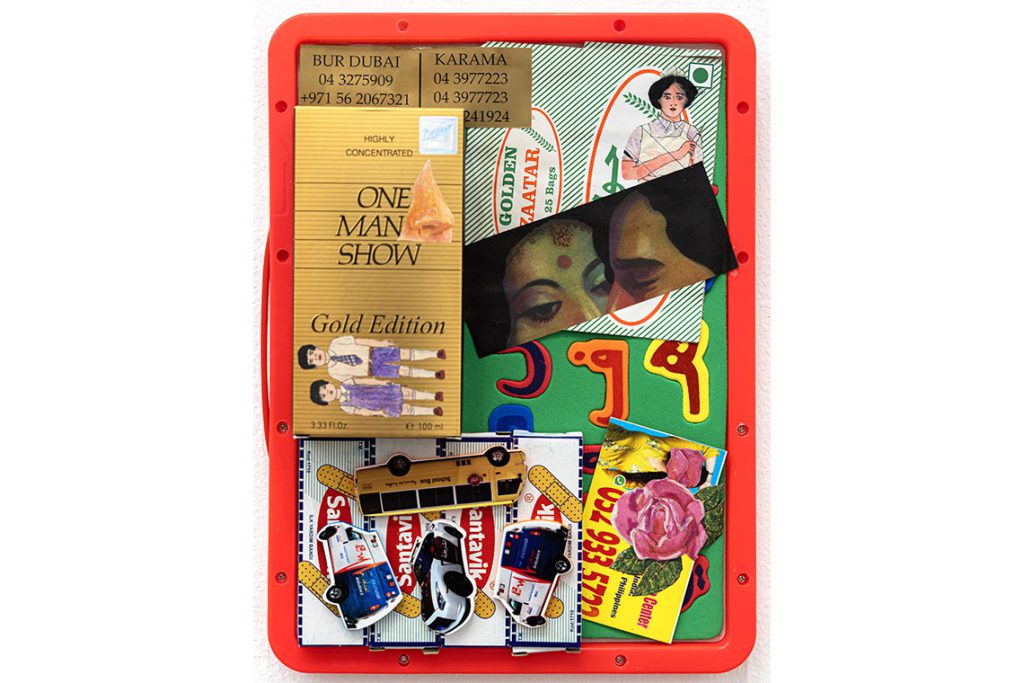

Similarly, Bady Dalloul’s collage-based miniature work One Man Show (2024) conjures up the everyday textures of life in old Dubai: golden phone numbers in Karama, yellow schoolbuses, taxis, garish little cards you find scattered on the streets, a Golden Zaatar packet and a cutout of covert lovers from old Bollywood cinema. It is a neatly framed nostalgia box. Throughout the show, work by artists like Dalloul and Al Qasimi prioritise capturing these contradictions of daily life in the UAE and the wider region, for those whose lives have been filled by them.

Appraising the works, however, feels less important than understanding how The Only Way Out is Through is as much a demarcation of an era – a season finale – as it is a provocation for the future. The show’s backbone is a timeline on the floor beginning in 2005, including various major global events, including those that have specifically impacted the gallery – the 2008 global financial crisis; Bitcoin; Israel’s Operation Protective Edge on the Gaza Strip; the COP21 Paris Agreement; the gallery moves to a new warehouse; Covid-19; the Beirut port explosion; South Africa’s genocide case against Israel brought before the International Court of Justice. The exhibition is organised into four sections from this chronology, culminating in the 2021–25 era of “polycrises”.

Any historiography is inherently unstable. But this timeline commingles with the art to assert the importance of this gallery’s story – its coming of age – within the archive of an extremely young and ‘spectacular’ nation. I fight my initial desire to search what has been left out of this history, rather than what is being carefully said. Still, I pause on the title, The Only Way Out Is Through, cousin to “it is what it is”. Basar’s curatorial statement acknowledges the phrase’s gravity yet memefied status. It is online lingo. It helps us cope. But we are living through genocides, the closest being in Gaza. This is a different kind of despair, as each day sediments more crisis on top of crisis. If the only way out is through this horror, what will we find on the other side? What will we make?

The Only Way Out Is Through: The Twentieth Line runs until 28 December