After an extensive pause for renovation, the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) in Marrakech has reopened its doors with a landmark exhibition, Seven Contours, One Collection.

One of Morocco’s major private institutions, since its 2016 inauguration the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) has primarily offered group shows dedicated to Moroccan and African art. Now, after a major reimagining that retains space for rotating exhibitions and commission projects – including inaugural contributions by Salima Naji and Aïcha Snoussi, as well as a dedicated solo exhibition by Franco-Moroccan artist Sara Ouhaddou – the new MACAAL has chosen to foreground its permanent collection of modern and contemporary work from the continent and the diaspora.

While works from the collection of MACAAL and its parent Fondation Alliances had in the past contributed to various exhibitions, they are now centred and elevated through a curatorial framework that is both precise and open. Guest curators Madeleine de Colnet and Morad Montazami were tasked with sculpting and contextualising more than a century’s worth of art, resulting in Seven Contours, One Collection, slated to hang for three years and with selected rotations of specific works already planned. As the title suggests, de Colnet and Montazami have compartmentalised the exhibition into thematic rooms, with titles ranging from the poetic (Promise) to the tactile (Transcribe).

Notable among the curational approach is the decision to employ, in the curators’ words, “performative verbs” in lieu of more standard nouns. Such a subtle gesture turns terms that might feel abstract or academic into something more active and alive. Instead of the rote “decolonisation” or “cohabitation”, the ideas are employed in French as infinitives (“décoloniser”, “cohabiter”) or in English as imperatives (“decolonize”, “cohabit”).

As such, these headings become invitations, and invigorating ones, especially when seen alongside the works themselves. Decolonize/Décoloniser is the first room one encounters, after passing though Salima Naji’s monumental 2024 mudbrick sculpture-cum-architectural intervention Dans les bras de la terre [In the Arms of the Earth], and sets the tone of the entire undertaking. Here, themes of colonial exploitation and restitution are explored in contemporary video (The Secretary’s Suite by the Canadian Kapwani Kiwanga, 2016) alongside works that tease out less explicit implications of domination on education (as in Hicham Benohoud’s 1994–2002 photo series, La salle de classe) and the body, as in a colourful painting by the beloved Moroccan autodidact ChaÏbia Talal and a hypnotic gouache from Algeria’s iconic Baya Mahieddine.

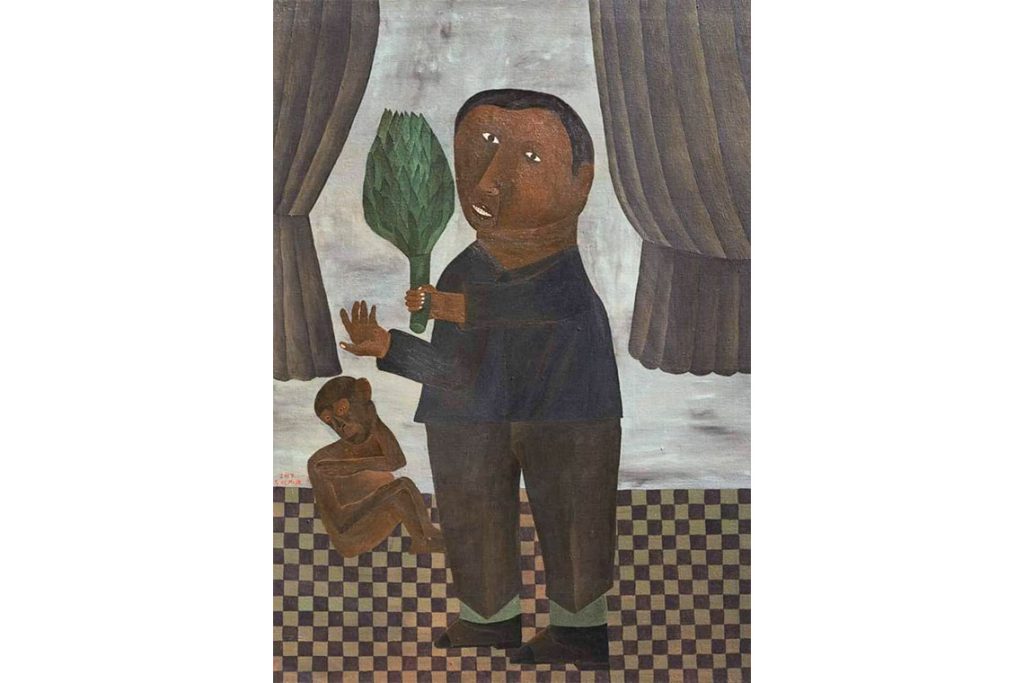

The variety of work and its dynamic presentation produces a well-calibrated balance between the contemporary and historical, the canonical and emerging, Moroccan and international, as well as the abstract and figurative. Such an achievement is on display throughout the other contours, as in the Initiate/Initier room, where the curators have placed Joséfa Ntjam’s Afrofuturist video art alongside Saad Hassani’s modernist painting Danse Ahouach Marrakech (1972). Elsewhere, in the hall collecting works under the evocative verb Weave/Tisser, a figurative acrylic by the underappreciated Sudanese artist Salah Elmur hangs near a minimal mixed-media work by Morocco’s Safaa Erruas. At times such balance exists within a single piece, as in Ahmed Cherkaoui’s 1965 painting YA’SIN, a highlight of the Transcribe/Transcrire room. Raw and colourful, the piece’s subtle and clever deployment of Tifinagh script interpellates specific audiences while remaining in the realm of near-abstraction for others.

At the entrance to several rooms the team has invited major international writers and thinkers to reflect on each term and its implications. These videos – more substantial than the single set of headphones and lack of seating might suggest – are serious, rigorous and reflexive, as evidenced from the first question posed to Ariella Aïcha Azoulay under the theme Decolonize/Décoloniser: “In what way is the museum a means of domination?” Such videos fit within MACAAL’s reimagined conceptual grounding; its approach to presentation is an emphasis on education and access, including a médiathèque and a separate hall on the second floor dedicated to an extensively researched timeline tracing the imbrication of contemporary art with post-independence African nationhood.

Extending outward to consider not only the greater continent and its global connections, the following and penultimate room – Promise/Promettre – turns inward, referencing Moroccan writer and theorist Abdelkebir Khatibi’s 1971 novel La mémoire tatouée as it reflects on the city of Marrakech. Placing works by Moroccan icons like Mohamed Melehi and Farid Belkahia in dialogue with a 1919 painting of the city by the Frenchman Jacques Majorelle – a rare inclusion by a non-native artist – the space feels both grounded in and punctured by a single photograph by Daoud Aoulad Syad entitled Marrakech, Mars 1986. A small, documentary portrait of a performer and a makeshift audience in the city’s Jemaa El Fnaa square, the image introduces a tension between the nature of the iconic gathering space – central, public, open – and MACAAL itself.

While free to the public and open to all, the museum itself is nonetheless located behind the imposing gated entrance of the extensive Al Maaden grounds, nestled alongside a golf course, condos and luxury dining. Once inside, visitors encounter art that is stimulating and rewarding, and the space itself – with a newly reopened café – is stylish and tasteful, yet it all feels both physically and spiritually isolated from the local and domestical public. One feels like an additional contour – Invite – is the only remaining element required to fully activate and engage with the works within the institution’s walls.

This article first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue