Showcasing an impressive array from the Barjeel Collection, a SOAS student-led exhibition demonstrates refreshing curatorial fortitude.

Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi continues to take the plentiful works from Barjeel Art Foundation, founded to preserve and manage his vast contemporary SWANA art collection, to fresh locales and instructive settings. The latest presentation is Hudood: Rethinking Boundaries, currently on show at SOAS University of London’s Gallery. The exhibition is part of Al Qassemi’s work as a Research Associate at the university’s Middle East Institute, and a collaborative effort led by his students there. Boasting a hefty line up of major names, such as Mona Hatoum, Manal AlDowayan, Kader Attia and Hayv Kahraman, among others, it is not just a privileged display of works from a rare and abundant collection, but incisively curated. This is a testament to the benefit of Al Qassemi’s mentorship, teaching and access to evidently sharp, clear-eyed curatorial students, who have mounted a show that in places has far more mettle than many comparable contemporary gallery shows today.

Hudood delves into how the term ‘boundaries’ and associated meanings can be both a creative subject as well as a useful framework for engaging the diversity of art from the SWANA region. This naturally means physical boundaries such as walls, borders and fences, as well as curatorial boundaries in the exhibition space, and the social boundaries of gender, state, urban design etc. It further includes intangible boundaries of memories, temporalities and perspectives.

The show opens with the initially unassuming Monde Arabe Sous Pression (2013), a mint ice cream-coloured aluminium pressure cooker by Batoul S’himi with the map of the SWANA region cut into it. It’s an excellent and refreshing opener, not least because rarely does such a modest object form an exhibition’s opening centrepiece. Yet it also succinctly captures the curatorial aim of opening up the entire melting pot of a “pressurised” region.

Hudood starts off with an exploration of urbanism and the built environment, reflecting on how architecture has especially been a site for understanding colonial and settler history, as well as a way of creating an idea of home. Works by Kader Attia and Aïcha Haddad offer juxtaposed approaches, while photography by Lateefa bint Maktoum and Ammar Al Attar mirrors post-oil industrialisation Gulf aesthetics. Al Attar’s 2012 images of prayer rooms in Dubai Mall and DIFC The Gate are particularly brilliant inclusions.

Manal AlDowayan’s porcelain birds, titled Suspended Together — Standing Doves (2012), offer a gorgeous transition into the show’s next section on gender. Her sculpture is of stationary birds frozen in place; upon peering closer, one realises that the white birds have a document printed on them, the permission from a male family member that was once required by Saudi women to travel.

Installation view of Hudood: Rethinking Boundaries at SOAS Gallery, London 2o24. Image courtesy of SOAS Gallery

Instead of proceeding with the often crudely simplified approaches to gender that one often encounters in exhibitions, Hudood specifically takes the majlis, the traditional gathering space for men, as an activation of the idea of how gender seeps into each nook of everyday life, from domestic activity to work to family life to rituals. Against scarlet walls, Zaha Hadid’s silver futuristic Tea and Coffee Set (2004) makes a stunning pair with Lamya Gargash’s Red Television (2009) from her Majlis series.

The final section of this floor returns to the tangible, taking the seemingly apolitical material of concrete as its unusual subject. Palestinian artist Khaled Jarrar’s 2013 Volleyball is a concrete rendering of the playground item, symbolising such a touching and tragic portrayal of the plight of war on children within the confines of a glass vitrine.

In fact, an entire section of its own on the exhibition’s lower floor is admirably devoted entirely to Palestine; given how inextricable the Palestinian question is to the history and present of the whole SWANA region, this seems only fitting and even necessary.

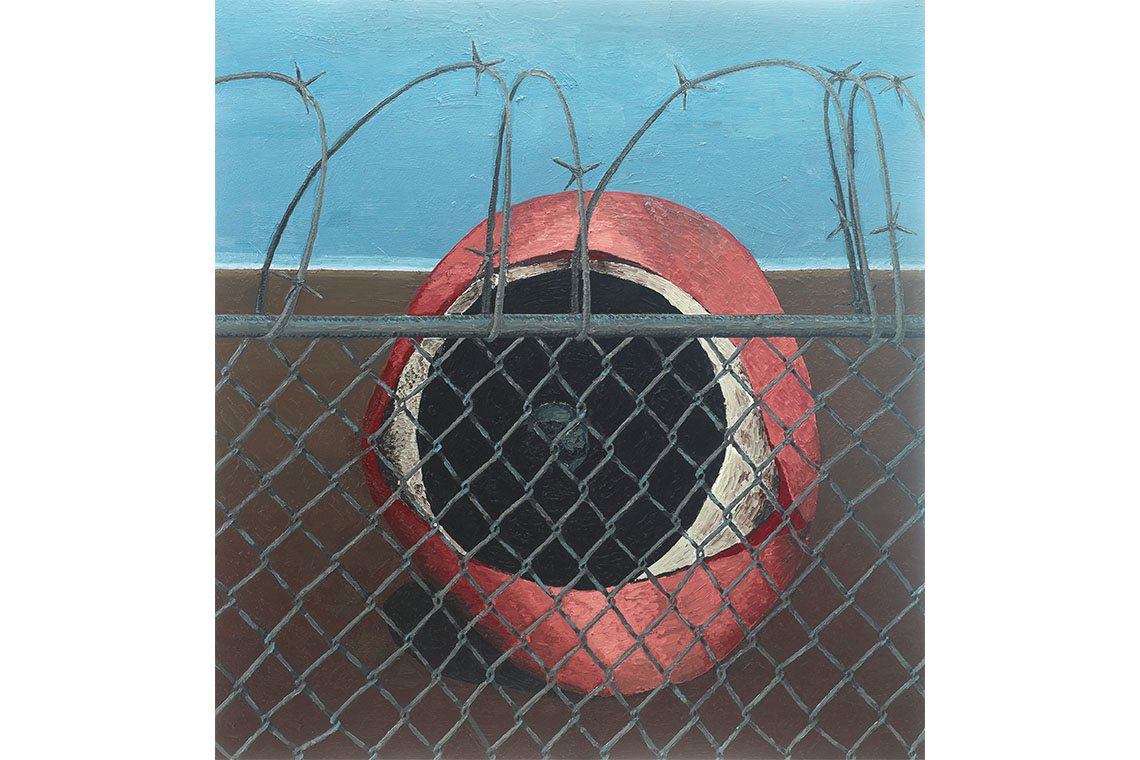

Yet the wider artworld has frequently been mum or complicit on this matter. In Hudood, we see Larissa Sansour’s fantastically satirical print Nation Estate (Living the High Life) (2012) together with prints by Fouad Elkoury, Taysir Batniji’s Pixels (2011) and Laila Shawa’s Walls of Gaza (1994) images, all preceded by a rich section on ‘Alienation and Belonging’ with works by Ahmed Mater, Mona Hatoum, Farah Al Qasimi, a video by Iraqi artist Adel Abidin and Tunisian artist Nadia Ayari’s heart-stopping painting of an eyeball behind a barbed fence. An additional section on ‘Cultural Porosity and Hybrid Identities’ further acknowledges varying narratives of diaspora and dispersal, underscoring the conditions that produce them – one striking work here is Walid Al Wawi’s blacked-out passport.

The show’s final section feels like an amalgamation of everything that has come before, touching on previous themes in different ways. With works by greats like Rachid Koraïchi, Anuar Khalifi and Latif Al Ani, this climactic portion blurs the boundaries of medium, time, geography and subject matter to produce a satisfying cadence to the exhibition. At this point, the journey through Hudood feels as hearty and filling as a warm meal, and an optimistic signal of what can be possible when curating art from the SWANA region, especially when led by fresh-eyed youth.