Curated by Freya Chou, Reem Shadid and Brian Kuan Wood, the Taipei Biennial reflects on our world as it has seemingly become smaller and questions if, because of this, there is more of an urge to break away or come together?

Entitled Small World, the current Taipei Biennial (opened 18 November) initially conjured up thoughts of jolly audio-animatronic dolls dancing around on a Disney-style ride, gleefully praising our interconnectedness and mutual understanding. A happy-go-lucky world. Yet, in the aftermath of the global Covid-19 pandemic, the exhibition points out that, perhaps for the first time ever in an age of social media and instant content creation, we have a common global experience linking us for better or worse. This 13th edition builds on the notion of shared events, unifying and dividing, good or bad, loss and gain.

Yet, heading to Taipei came at an unsettling time. A celebration of art and togetherness against the backdrop of Israel’s war on Gaza and a mounting civilian death toll seemed potentially incongruous, yet the brutal event has once again prompted people to come together – and, indeed, sometimes part – through the possibilities offered by social media: journalists risking their lives to stream online the realities on the ground, protests taking place around the world, and digital knowledge-sharing in an attempt to create change and acknowledge decades of oppression and apartheid. It was hard to ignore the current climate, even more than 8000 km away.

This was perhaps most evident with co-curator Reem Shadid’s introductory speech on the opening night, with lines from the Syrian poet Riyad Al-Saleh Al-Hussein, and during Samia Halaby’s kinetic painting performance with Julian Abraham (Togar), which included percussion sounds, singing and recent protests chats such as “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” as the algorithm reacted on screen with an array of colours and patterns. The emotions prompted by the ongoing attacks on Gaza were deeply felt by many of those present at the opening of the Biennial. How small the world has become is somehow more evident than ever.

Yet there is an eeriness to acknowledging global current affairs, in a surreal thread of doom scrolling punctuated with the latest recipes, sales and the hottest make-up trends, raising questions of sincerity and our numbness. Or are we simply overwhelmed? Has instant access to all corners of the globe isolated us instead? The exhibition delves into the links created during the pandemic and the liminal space between growing closer and further apart. The pandemic undeniably changed everyone’s lives: some met with loss and fear, the familiar became unknown and others explored new discoveries, inwards and outwards.

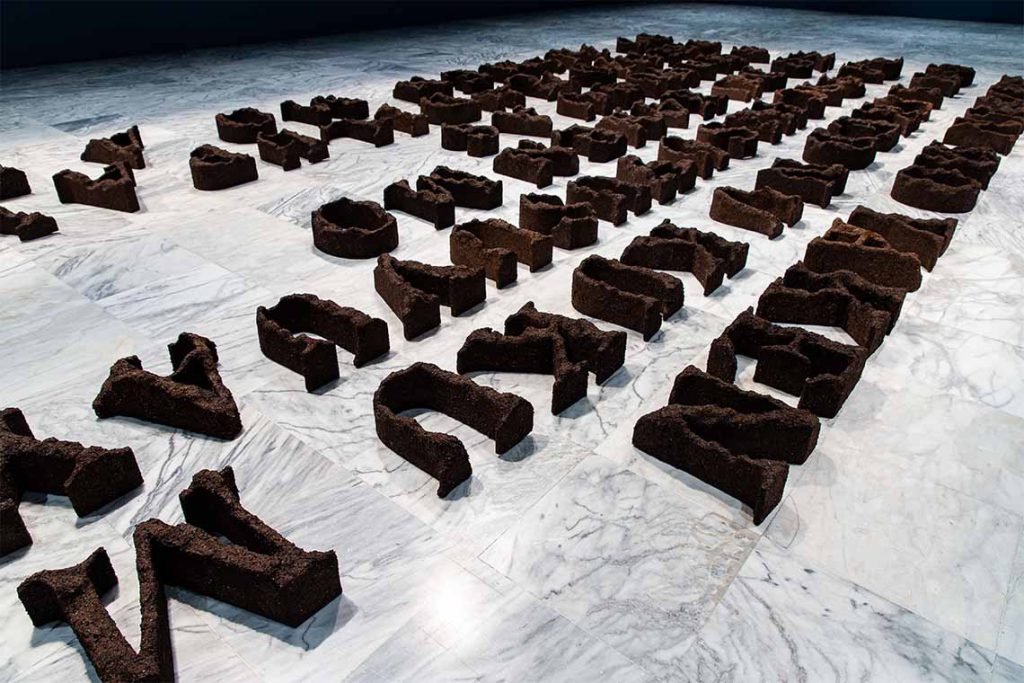

During the opening press conference, the three curators referenced cases of the world becoming smaller through the pandemic with the examples of a Himalayan village that could finally see the mountains as the smog subsided and areas where birds could finally be heard without the usual noise pollution. Pio Abad’s research-based commission Laji No.97 (2023) is grounded in a trip to Lanyu, an island just 70 km from the coast of Taiwan. The Yami people of the island are closely related to the Ivatan, an ethnic group of the Batanes islands in the northern Philippines and of which the artist’s family are a part. As folk history goes, the Yami’s ancestors came from Batanes seeking refuge from Spanish colonisers. The work consists of large terracotta letters forming Ivatan poetry known as laji (and bearing a resemblance to spoken verses on Lanyu), which originated in oral tradition, accompanied by booklets in which Abad documents selected laji and photographs from his trip. Reflecting on the geographies, Abad’s work highlights finding familiarity in unfamiliar.

On the other side, what happens when somewhere familiar becomes distant? This is the case in Basim Magdy’s 2014 film The Dent, a narrative surrounding a small town that gets lost in its development and ambitions for international recognition as its world develops and expands. Raed Yassin connects distant geographies through his seven porcelain vases entitled China (2012), which depict scenes from Lebanon’s Civil War (1975–90). Produced in Jingdezhen, renowned for porcelain production, and illustrated by a Lebanese comic artist, the vases are rendered with the testimonies of former fighters in the style of Persian miniatures. The work links continents but also raises concerns over pop culture, mass production and what it means for those reproducing tragedies. Do empathy and connection become artificial or are we building bridges and connecting? Perhaps we get so wrapped up in ourselves that we forget about the world around us, but through the pandemic we may be closer now than ever.

In the basement garden courtyard is Natascha Sadr Haghighian’s new commission Watershed (2023). Six installations create a spatial sound arrangement with beeps and noises reminiscent of a hospital ward, culminating in a melody with new lyrics based on a love song by the late Hong Kong pop star, Anita Mui. With airplanes flying low overhead, the loud roars of the engines merge with the immersive 40-minute audio; there is a palpable tension in the air. Morphing translucent figures, with discernible heads of rabbits or legs with hooves, are frozen in a state of flux and appear to be bursting out of walking frames, as if they were either trapped or about to escape. Haghighian noted that the work looks at social contracts and how we determine what is considered human or worth saving and caring for. Who might decide this? All are questions leading towards a discussion on collective behaviour and what societies value. For Haghighian, the work initially stemmed from a conversation about loved ones with dementia, considering concepts of care and, more broadly, what happens when the world we know becomes unrecognisable or when we ourselves are no longer recognised.

Jacqueline Kiyomi Gork’s installation also provokes anxieties and emotions through sound. A pitch-black room hosts a giant inflating and deflating structure in Not Exactly (Whatever the New Key Is) (2017–ongoing), creating tension between machine and viewers as viewers breathe together with the piece while comprehending their environment. As with Haghighian’s work, a voice eventually cuts through the space to provide a form of relief, a human connection.

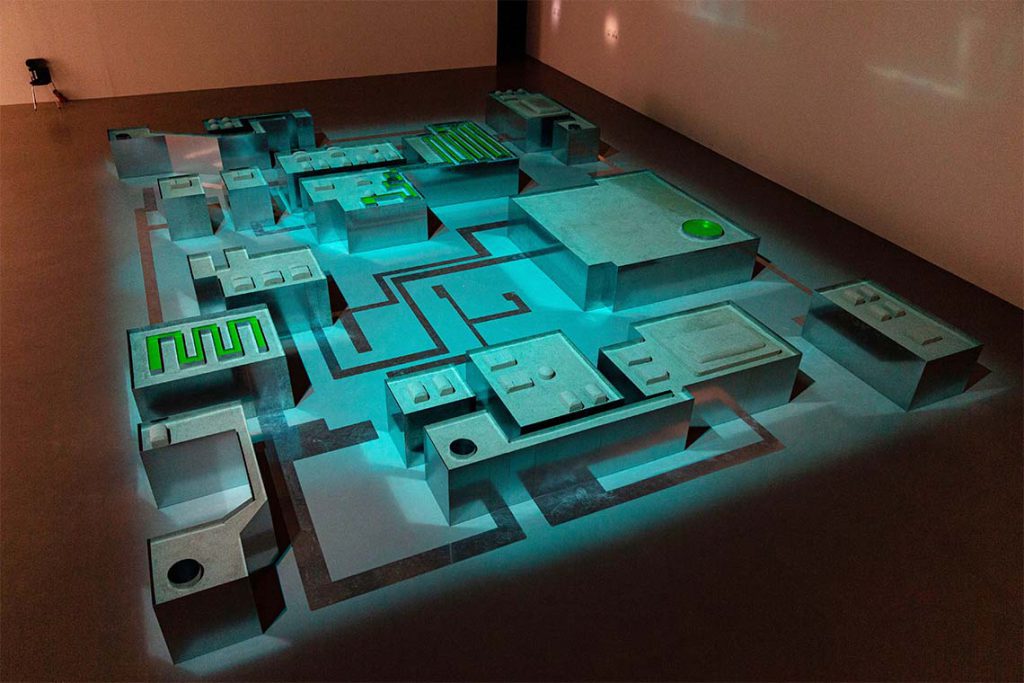

The role of technology is a strong thread throughout. Most of us spend significant time each day on Zoom or social media, even more so since the pandemic, and now the hot topic of AI has raised the stakes even higher. Li Yi-Fan’s What Is Your Favorite Primitive (2023) narrates “a death match” between the artist and their software while grappling with the production process. In a fight between social and ethical concerns, it also raises questions of image production and communication. Nadim Abbas’s large-scale Pilgrim in the Microworld (2023) goes beyond the screen to create sand bunkers, which when viewed from above resemble the infrastructure of a computer circuit board. Ever crumbling, the sand will be replaced for the duration of the exhibition, underlining how the work looks at ruin and regeneration, the stability of expansion and the scalability of new technologies.

Jen Liu’s video The Land at the Bottom of the Sea (2023) – the last chapter in the artist’s Pink Slime Caesar Shift project – looks at the breakdown of technology to provide solutions to environmental and social problems in China, while also highlighting the overbearing government pressure on NGOs and labour activism. An online digital archive is also available, providing users with access to images, texts and videos about Chinese women who have “politically disappeared” – some purged from digital existence, others found drowned as a result of their political activism. Also highlighted are victims of gender-based violence and immigrant poverty, in a powerful work that underlines the very real consequences of technology.

The Taipei Biennial has cohesively encapsulated the anxious hum permeating our lives, of something familiar growing distant or the wish to be closer to the unknown. A new and common feeling, a desire for human connection as we navigate a new post-pandemic era. In a world full of paradoxes and tension, has a smaller world changed how we interact with each other? With our increasing reliance on technology, we must look at how small the world has become and and consider if it is perhaps time to pause and and understand the area in-between.