Shifting between absurd, humorous and mythic registers, the artist’s practice is grounded in Saudi Arabia’s societal transformation and its manifestation in visual culture,

“I feel like a ghost sometimes,” says Ahaad Alamoudi. “At different times I’ve been in the dark, felt I had no voice, or been positioned in a way that I feel that I’m here but not here.” The spectres of past depictions and traditions, and their filtering through contemporary media and values, hangs almost imperceptibly throughout the artist’s practice.

Alamoudi – whose academically rich works flit between various media, from textiles and photography to video installations and open-air theatrical presentations – revels in the strange spaces found between the fixed and known. Currently studying for a PhD at the Royal College of Art (RCA) in London, she meets me in the clink and clatter of the café next to the college’s imposing new building. It soon becomes clear that she has birds on her mind.

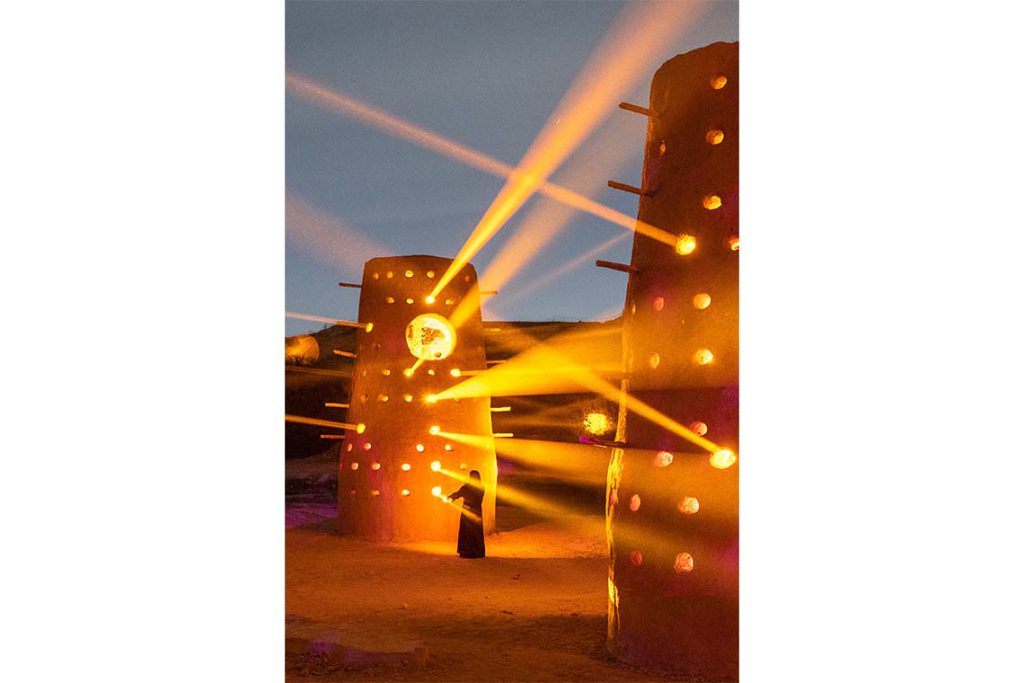

Her most recent work, Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow, was a site-specific installation presented at Noor Riyadh 2022 and featuring two purpose-built pigeon towers with live performers in each. Dramatic light displays and evocative sequences of singing linked the two structures, which were erected in the Wadi Hanifah and designed by Alamoudi to act as carriers of information. Working with an architect and local artisans, Alamoudi built the mud-brick towers using red wadi clay, sun-drying the bricks on the ground in a time-honoured manner. “I wanted the towers to be as traditionally made as possible,” she says, “the one addition being the windows I created for my performer.”

We Dream of New Horizons, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist

The installation marked a shift, at least in form, away from her video pieces, such as The Green Light (2022), in which film footage showed a chorus of men triggered to sing by the titular illumination. “I see what I do within video as a form of staging,” Alamoudi explains. “The only difference between the Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow and The Green Light is that there’s no lens. The viewers are participating in real time.” In her video work, she notes “There’s a power to the edit, a voice that I have when I edit a piece. This is what makes my work what it is. With Ghosts of Today and Tomorrowit was quite scary for me to lose that control and to allow things to just happen.” For her audience at Noor Riyadh, the landscape and the elements shaped the work in their own ways “The wind gushed, the sun went up, the smoke allowed the light to be thicker at times,” Alamoudi recalls. A lens, she explains, just wouldn’t capture the magic of such moments.

The ephemeral nature of the pigeon tower piece alludes to the oral history of folklore: the work is gone, and people will remember and talk about it in different ways. “What is left behind is just the two structures,” she says. “Now people question whether they existed before I placed them there.” Ghosts of Today and Tomorrow is therefore best seen as a work about people or voices that are present but not seen – ghosts, in fact – and bring a sense of mythology or legend to their presence.

Born in Jeddah in 1991, Alamoudi was raised between Saudi Arabia and England. Her mother, Dr Effat Fadag, is also an artist and an academic. As a child, Ahaad became interested in timeless tales and grew up immersed in fictional worlds, from One Thousand and One Nightsto translated Anime shows.”I do read a lot of folklore and I grew up around a lot of stories,” she says. “I don’t know why they lean into me.” Alamoudi studied visual communication at Dar Al-Hekma University in Jeddah, graduating in 2014, by which time she already knew she wanted to be an artist. An MA in Print at the RCA introduced her to printing on fabrics and, subsequently, to using those materials as filmed features within her video installations. Her central topic has remained the rapidly evolving context of Saudi Arabia and how the changes in society materialise in visual culture.

Image courtesy of the artist and ATHR

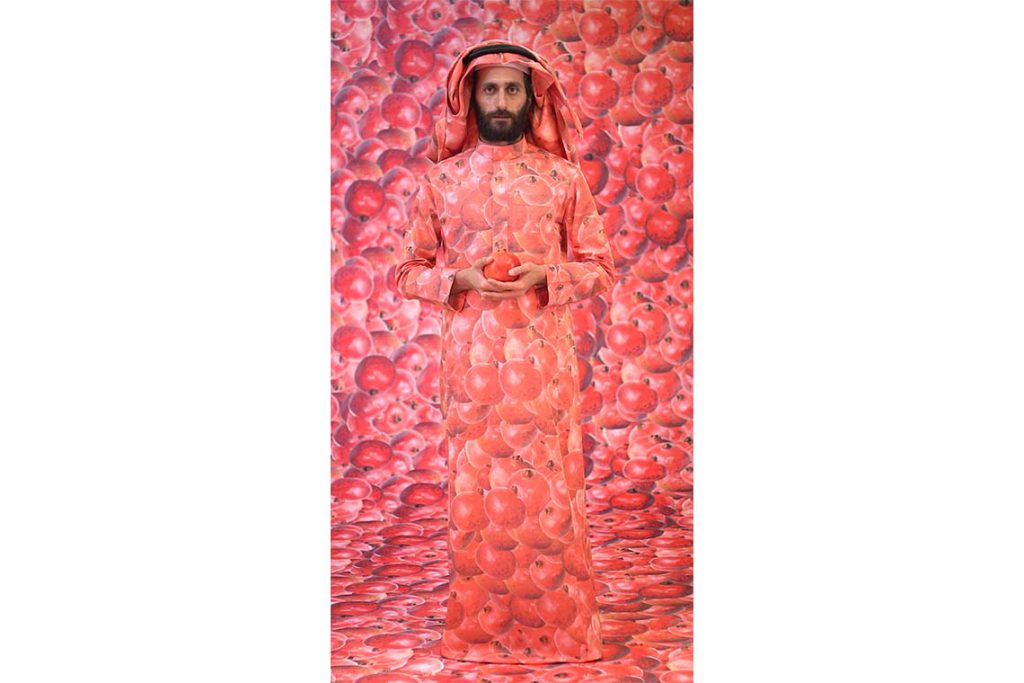

Her work has been consistently diverse, incorporating online memes and video clips and even including her own Instagram account. She addressed gender roles in Self Portrait as a Pomegranate (2017), a video installation of a man wearing a pomegranate-designed thobe and shemagh. For I Was Told Ice Wouldn’t Melt in Heat (2019) she filmed a man watching 250 blocks of ice melt in the desert. “I didn’t know what the outcome of that effect would be. How long would it take for the ice to melt, how would the performer react? There was also a sandstorm happening on the day, as you can see in the footage, and we were being told that we had to leave the location.”

Such works point towards Alamoudi being a storyteller with no conclusion. She is particularly interested in the inexplicable and strange aspects of collective identity, she says. “When I first began producing work, humour was coincidental. It just became part of the work, it wasn’t a part that was chosen. Then I really leaned into it.” She was reacting to what she calls “the absurdity of how I was feeling. The things I was witnessing felt surreal to me.”

Humour, she observes, has always been “a powerful tool to address sensitive topics” in a region that, post 9-11, was often depicted in a negative light. “Everything was really dark, so humour was a means of addressing these dark topics in a grounded and more accessible way.” It was a coping method, she says, one that she had noticed among her community and in music and television shows. “I think it was a particular language that the country used and continues to use.”

Image courtesy of the artist and ATHR

Earlier this year Alamoudi created a video piece called Liquid Dune for the Italian fashion brand Roberto Cavalli to promote its new perfume. What she describes as “an adventure to celebrate Middle Eastern culture and art” is perhaps an unlikely partnership, although, having previously created textile prints, she thought that Cavalli’s branding and patterns were a natural fit for her. Cavalli’s marketing campaign pictured Alamoud cradling scent bottles and striding over sand dunes in flowing outfits. When I saw the images on her Instagram I thought it was spoof. “I love that you reacted like that,” she chuckles. “I often think that the work that I do, especially on social media, can come across as a parody in so many ways.”

At this point in our interview, Alamoudi pauses, laughs and points above my head at the neighbouring RCA building. Looming over us, the new block has latticed brickwork with gaps left in-between the bricks. “The architects built this not thinking that pigeons were going to take over, so now there’s a pigeon issue,” she says, pointing out the spaces where the birds roost. “Pigeons have taken over the RCA.” This accidental pigeonnier is the perfect Alamoudi subject. “We’re in classes sometimes and we just see pigeons by the window, swooping about or mating or whatever,” she says. “I love it.” The moment encapsulates perfectly her interest in the intersection between wit, history and serendipity.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 109: Smoke and Mirrors