Deeply immersed in the architectural traditions of the Hejaz, the artist seeks beauty and balance through preserving longstanding craftsmanship.

When I mentioned I was writing a profile of the Saudi artist and designer Ahmad Angawi to an acquaintance who had worked with him, his response was an unusual one. Angawi, he told me, might be one of the most laid-back people he had ever met, never in a hurry, always waiting until the moment is right. The description certainly chimes with the character of Angawi’s work and the fundamental principle that underlies it. He refers to this central tenet as Al-Mizan, or ‘balance’, entailing concerted effort to achieve equilibrium and harmony, both in spiritual terms (it is, after all, a guiding principle of Islamic aesthetic tradition), and its practical application in his work. “It’s a tool of thinking,” Angawi tells me. “This idea of balance is linked to many cultures around the world, and it can be applied in design, it can be applied in art. Mizan is a key word in our time and age.”

Perhaps the most obvious manifestations of this ideology come courtesy of his insistence on equality between form and function; and on the skilful balance of the time-honoured craft practices of his native Hejaz, complemented by 21st-century technology. It’s hardly surprising that Angawi should place so much importance on traditional craft. Born in 1981 in Makkah – a city that was soon to replace much of its architectural heritage with futuristic hospitality establishments – he grew up in an environment where creativity was of paramount importance.

His father, Dr Sami Angawi, a revered architect and the originator of the Mizan theory, turned against fashion by building the family home in Jeddah in the authentic local style. “We always call it the House of Balance,” Angawi says. “It is very Mizan!”. As a child, he liked to spend time in his father’s workshop, a hive of activity always full of craftsmen from across the Middle East and North Africa. He observed them at their benches, taking in the secrets of their trade and marvelling at the intricacy of their handiwork. This first-hand experience of intensive, skilful labour allowed him to look at the built environment around him in an entirely different light: he started to see it, he says, as “an open museum”. He would stroll through Al-Balad, Jeddah’s old city, wondering at its vernacular architecture and pondering the different processes that had gone into its creation. What struck him was its simplicity, its dependence on local materials, its durability and its incontestable elegance.

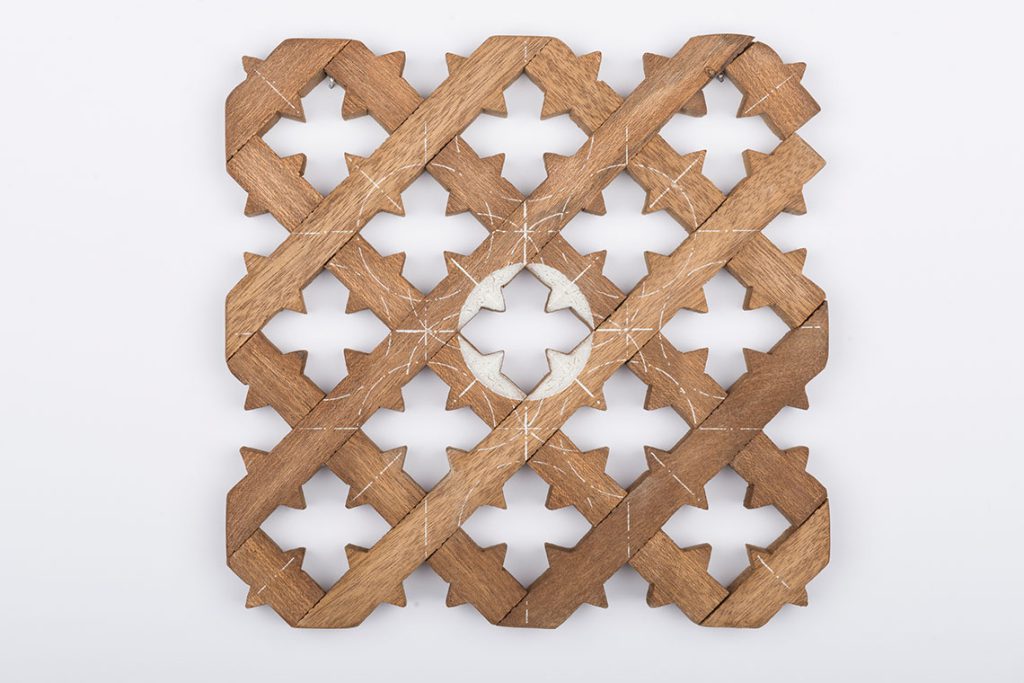

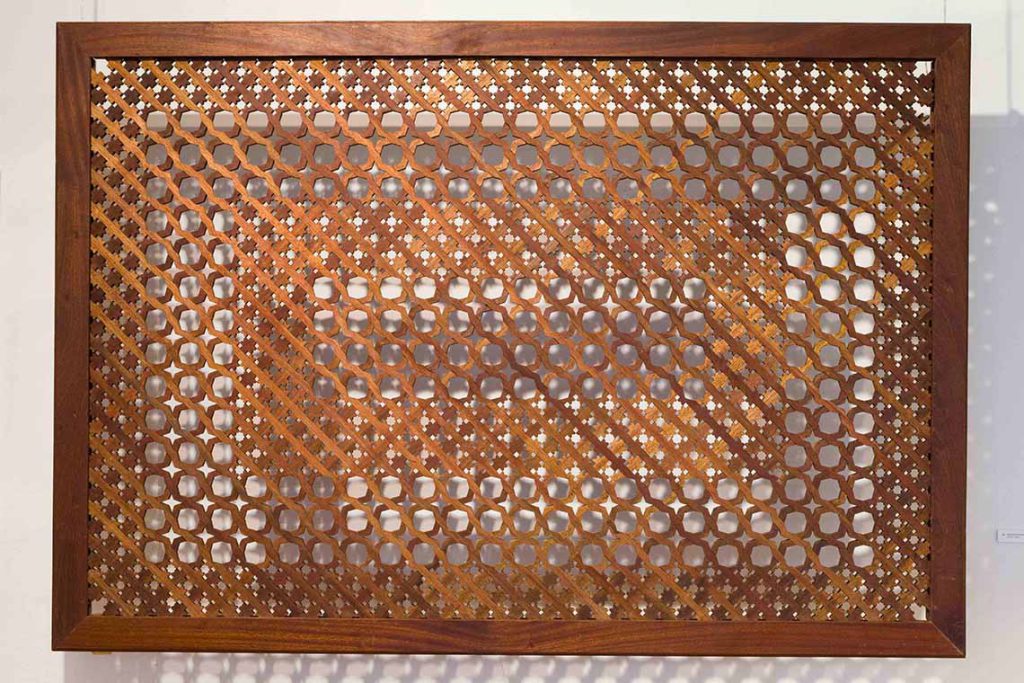

More than anything, Angawi was fascinated by the distinctive, corbelled bay windows of structures in this part of town (known as rawashin) and the exquisite latticed screens (mangour) that covered them. With roots dating back to the Abbasid period (c.750–1258), these prominent wooden coverings are perforated with small apertures in fabulous geometric patterns, allowing natural light and fresh air to enter a building, and affording those within both a view to the outside and total privacy for themselves. They simultaneously conceal and reveal, a duality not lost on the future artist.

He later travelled to New York to study industrial design at the Pratt Institute, where he started to create pieces that married design, art and spirituality. An early project, for instance, saw him creating a bag to carry his college books that, through the addition of a flap, could double as a prayer mat. One thing that became clear to him, he recently told UNESCO’s Revue du patrimoine mondial, was that “today’s industrial designers are the custodians of these age-old crafts in our rapidly evolving world.” Design, he realised, must respond not just to the given brief, but to its social and political context. As he saw it, the boundaries between design and art were endlessly porous. His expertise honed in London at the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts, where he concentrated on the kind of wood shaping that had so inspired him back in Jeddah, he set about putting his creative ambitions into practice.

A typical Angawi creation will respond to all of his chief concerns. Even when the aesthetic of Makkawi heritage is not evident, it is present in spirit. For his ongoing, Arab Spring-inspired Street Pulse project (2012–), for instance, Angawi set up recording hotspots at locations across Jeddah into which passersby could record their thoughts. It has been put on display in the form of a giant ball of microphones, next to which visitors could listen to the monologues on headphones.

A more typical work, however, will involve the artist retreating to his studio to set to work on traditional materials with both the simplest of tools and modern manufacturing techniques. As Angawi sees it, heritage techniques must be complemented by technology to keep them alive and accessible. His main inspiration, though, remains the mangour window screens of Jeddah. He himself has produced a dazzling array of responses to their serene aesthetic, including items of furniture and design in addition to window pieces.

An achievement particularly close to Angawi’s heart came in 2017, when he was invited to contribute five new mangour to the Victorian sash windows of the British Museum’s Gallery of the Islamic World. The new features were created in collaboration with the Factum Foundation, their production combining state-of-the-art digital cutting technology with extraordinarily complex handcrafting. Hewn from 280 stripes of black walnut wood, a material native to Europe and thus responsive to the local environment, Angawi’s mangour are a triumph of site-specific craftsmanship, delicate creations in the midst of which are set impossibly complex interlocking patterns. Individually, they represent the body, mind, spirit, heart and soul. “It was a real statement,” Angawi says. “Each window was a celebration of a different technique. The ‘heart’ window, mainly, was made using hand techniques.” As you walk around the room, each successive window features more and more input from machinery.

Angawi has since ridden the wave of Saudi Arabia’s dual contemporary art boom and cultural tourism drive, exhibiting across the Middle East, Europe and the USA. Increasingly, his focus has been on passing on the traditional crafts of his homeland to a new generation, ensuring these skills are not lost to history. He holds several positions with heritage and educational foundations, most notably serving as director of programming at the House of Traditional Arts in Jeddah, a collaborative initiative between Art Jameel and the aforementioned Prince’s School in London. Here, students are taught all manner of local artisan practices, from product design to architectural conservation, many of which have until recently been at risk of extinction. Incredibly, it is the first such establishment in Saudi Arabia, and has done much to revive interest in that country’s cultural patrimony since its foundation in 2015. “I am so proud to see some of my students now are teaching at the school,” Angawi enthuses.

In the long term, he is attempting to document every piece of information he can find on his beloved mangour, including those constructed for buildings that no longer stand. While much of Jeddah was spared the serial destruction that has befallen other Saudi cities – its mayor adopted a conservation strategy as early as the 1970s – many fine examples have been lost. Angawi’s aim is to produce a book on the subject. “It will be great for any researchers, anybody interested in the craft,” he explains. “But there are so many ways to interest people. Even now, we’re working to produce it as a puzzle for young kids to play around with! I’m interested to go into that further.”

Angawi’s current plans revolve around the future of Jeddah as a creative hotspot. “I have a studio where we’re trying to introduce all these [traditional] elements of design into contemporary Saudi buildings,” he tells me. “We’re also working with international architects who are interested in this. But I’m really interested in environment and community. I’m working with a project called Zawiya 97, which is involved with the history of Old Jeddah, and we’re creating an environment for artisans and makers, introducing a makers’ space that has the modern technology but also the simple tools used traditionally. I really hope it can be a medium to revive the city, to create objects used in contemporary houses that have this aesthetic link to the past, and offer something to the community.”

His ambition, however, is more simple: to be a craftsman and to celebrate craftsmanship, whether by hand or digital, “because that principle of craftsmanship, how it affects you as a person, is something that we started to lose.” On the basis of his work so far, it seems he is well on the way to rediscovering it.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 111: Crafting the Contemporary