The latest edition of the MENART fair returns to Paris and at a new venue, showcasing works that tantalise and provoke in equal measure.

The average art fair can be an underwhelming experience. It displays the disciplines it purports to represent in the most nakedly commercial, and necessarily least interesting, light. It is crowded with ugly advertising and second-rate art, all for the most part housed within an exhibition space ill-suited for the specifics of the dubious material its organisers aim to shift, with little thought to geographical specificity or curatorial competence. Taking all of this into account, you might approach the fourth edition of MENART Paris with a heavy heart: but trust me, you’ll leave wondering why you ever had such reservations in the first place.

First off, the space. The venue is the Palais d’Iéna, almost certainly the masterpiece of the hallowed architect Auguste Perret. It is a semicircular gallery composed of high ceilings in reinforced concrete and an ammunition belt of soaring, plate-glass windows. Indeed, according to the editors of the Guide d’architecture de la ville de Paris, 1900–2008, it is “one of the most beautiful achievements of 20th century architecture, and could quite correctly be described as a perfect monument”. It is, in short, an ideal venue for exhibiting visual art.

Second, the focus. MENART, which evolved from the Beirut Art Fair, specialises in the work of artists from the Levant, the Gulf and North Africa – many of whom have yet to claim much of a presence in Europe. It’s beyond doubt that much of the most interesting art being made today is coming from this region. That is the reason I write for Canvas; and, presumably why the opening night was packed to its béton armé rafters with young French artists eager to see what their contemporaries in Lebanon, Egypt and the UAE are currently up to. Although art from these countries is increasingly visible here in Paris, we seldom get chances to see so much of it in a single space – let alone one as sumptuous as this.

In a critical sense the fair can be read in a few ways – perhaps most obviously, as an exhibition of contemporary painting from the Arab world. In this respect alone, it would be a fascinating survey. What we have here is the modernist canon being reshaped, repurposed and inserted into a new context entirely, and the result is infectiously arresting.

Witness the work of Iranian artists Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian, who open proceedings with a metal structure that looks for all the world like a paralysed Alexander Calder mobile. Several arms shoot from the spine of the piece, each bearing a ceramic paint onto which have been painted a smorgasbord of surreally violent scenes: dismembered arms wave Kalashnikovs, sinking ships sprout Louboutin stilettoes, weird hybrid animals colonise deserted suburban streets.

More conventional but no less sinister thrills are to be had at the UAE’s Hunna Art. A handful of photorealistic still lifes by Palestinian painter Reem R create uncanny atmospheres from plausible arrangements. In one, a plastic baby’s dismembered hand points up in a “heil!” gesture from a swathe of purple velvet, which it shares with a McNugget Meal (complete with supersize soda, naturally) and a wilting fleur de lys. All these elements appear to be recurring motifs in her work, which goes one further than Magritte by conjuring extraordinary effect from emphatically ordinary components.

Image courtesy of NIKA Project Space

A very different but spiritually aligned voice can be seen in the paintings of Aliyah Alawaleh, who draws on Cubism and the weirdness of interwar German expressionism to articulate what it means to be an independent female artist in the Emirates today. Her figures – or figure, as there seems to be but a single, recurring woman in these paintings – are either eating each other, eating consumer-branded goods, or are themselves trussed up to be eaten for a ceremonial dinner. These paintings rasp with anger and punishing introspection, and are all the more powerful for it.

An altogether quieter variation of this reinvention of form and register comes courtesy of Layla Dagher at Beirut’s Art on 56th. Drawing on Symbolism and Post-Impressionism, Dagher’s acrylic painting Beside My Cat (2023) captures a young girl and her titular companion staring out of a huge picture window towards an imagined, Cézanne-esque coastal landscape. The sense of confinement created by the artist’s division of space gestures unmistakably towards the loneliness of the 2020–21 Coronavirus lockdowns.

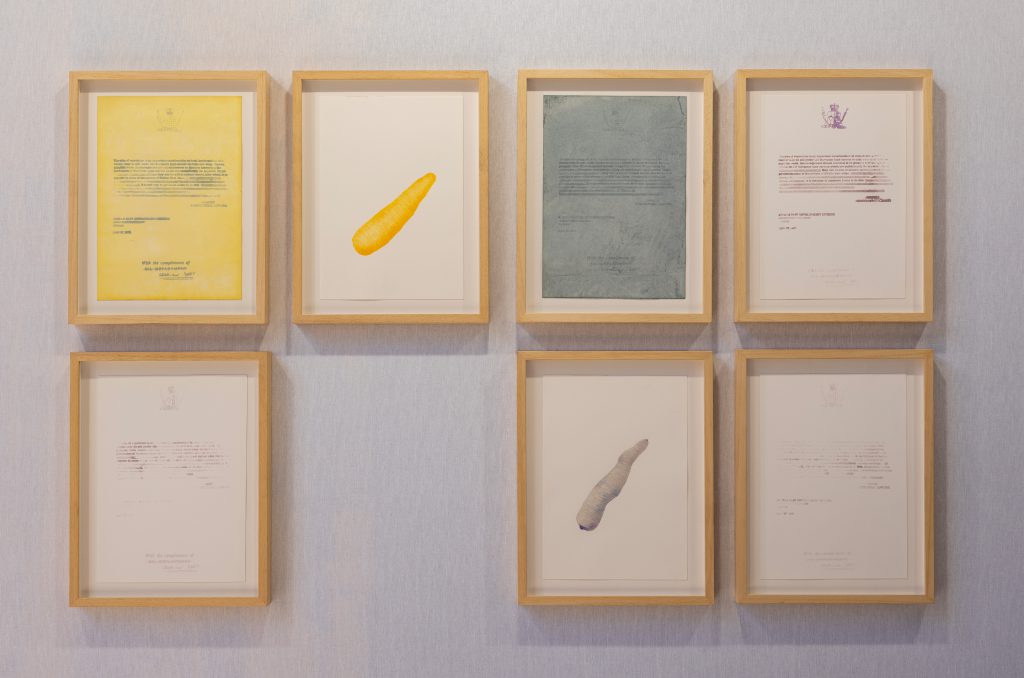

None of this is to say that traditional form is sacrificed in the name of postmodern reinvention: witness Yousef Ahmad’s intricate collage pieces at Doha’s Al-Markhiya, wherein lines of unreadably dense calligraphy dissolve into thickets of small palm-paper tubes protruding from the surface of the piece. Or, in a less literal sense, Fatma Al-Ali’s mini-show at NIKA Project Space, where the artist uses colonial-era agricultural documentation to reveal how the British government of what was then known as The Trucial States mandated that only certain genii of vegetable should be grown on their territory. As a result, Al-Ali demonstrates, the purple carrot native to the region was entirely supplanted by the more common, orange variant. She has fielded a small ink drawing of the extinct vegetable that will gradually fade to nothing, leaving only a print as a memory.

There are minor complaints, certainly: a few pieces here are relatively indifferent, and I can think of a number of artists from the regions covered, particularly of Palestinian and Algerian nationality or origin, whose presence at the fair would have been more than welcome. But though you could often fool yourself otherwise, the event makes no claims to be an encyclopaedic exhibition of art from the MENA countries, and its quality ratio is never less than impressive. Perhaps most encouraging of all, much of the best work it contains comes courtesy of women artists born after 1990. In this respect, it provides real excitement for what might be to come.