The multidisciplinary artist reflects on a career of artistic activism, cultural conservation and creative innovation, blending inquisitiveness, architecture and her Moroccan heritage.

Canvas: Traditional weaving and textiles are a recurring element in your art. What draws you to work with these crafts?

Amina Agueznay: My practice is very matter-based. Throughout my career, I have had phases of working with stone, wood, plastic and shells, and I suppose I still have a lot to say with textiles. It is all about scale. Weaving or hand-crocheting wool, for example, enables me to go from minute to very large pieces. As an architect, spatial intention and scale are important considerations. Installations are often site-specific, evolving as they move from one space to another. I play with scale, from the very small to the monumental. Yet often the process of discovery and collaboration is more interesting to me than the finished product.

Many people see contemporary art and traditional craft as separate practices, so how do you strike a balance between the two?

I see them as one! I used to talk about creating bridges between craft and art, but now I see them as being one and the same, because stories are woven in the intangible. They live in the process, and the stories told are often as important – if not more important – than the finished product. I studied architecture in the USA and practiced there for a few years. When I returned to Morocco, I started animating creative process-oriented workshops for artisans who had different know-how, working with various governmental agencies in Morocco to empower artisans – both male and female – and to create new products for new markets. These workshops enabled me to identify the type of work that I wanted to do personally, and with whom I wanted to work on my artistic projects.

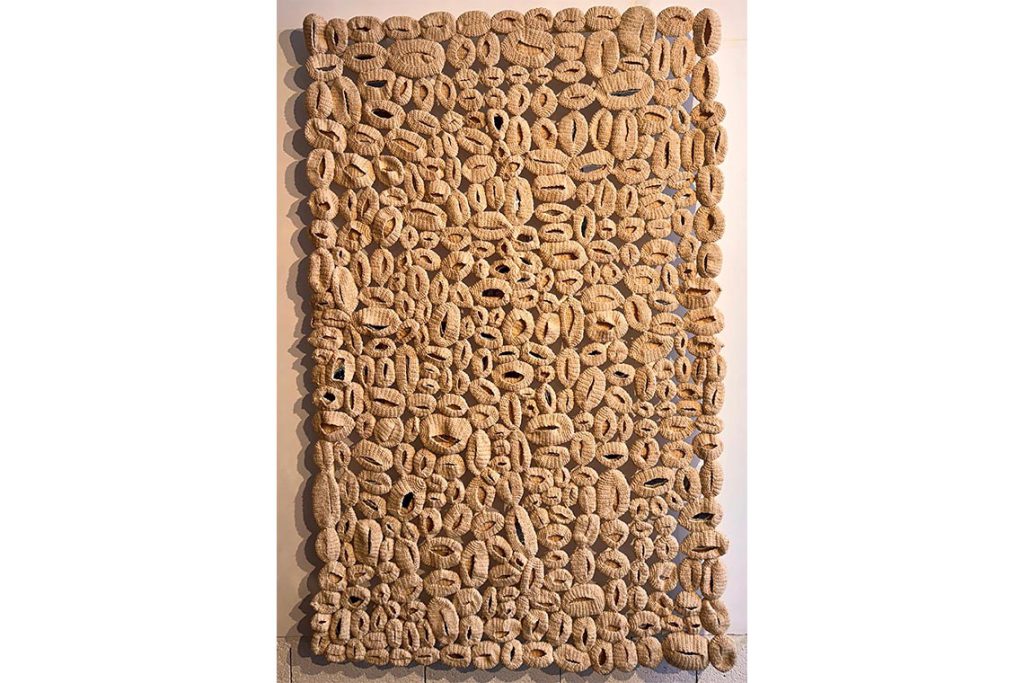

You also combine elements of traditional crafts in unexpected ways, such as in Enfouissement (2024). What did you hope to convey through this unusual work?

With Enfouissement, I deconstructed the jewellery forms that have long been part of my artistic vocabulary to create a metaphorical alphabet. Burying the jewels in textile is my way of writing a story with these talismanic objects, a way of providing protection.

Your approach is very researched-based and you work extensively with local communities and artisans. How are these experiences incorporated into your artwork?

In parallel to my artistic practice, I have travelled extensively in urban and rural areas across Morocco, seeking out artisans in order to catalogue their techniques and practices. This research inevitably impacts my own contemporary interventions, underscoring the collective, collaborative or participative nature of creation. I see my work as ‘process-based’. Although I work in multiple media, I find that textile work is particularly communal and it is important to me to work with craftspeople. My journey as an artist was not a planned one; it was – and still is – based on who I meet, and what potential I recognise. Most of the workshops I was invited to participate in were in rural areas. I liked meeting the artisans from these places, discovering their knowledge and skills, and satisfying my own curiosity. I really enjoy being on the road and being attentive to landscapes, both on the larger scale and in terms of their unique matter. On a smaller scale, I love being welcomed into the ateliers of artisans. I enter their worlds, discovering new experiences and techniques, new motifs and colour combinations. Even though I have an archival atelier, a material library basically, my real atelier is out in the field, in the artisan’s environment. That could be with a rug weaver, a potter or a basketry weaver. I consider these is a great collaboration and fantastic exchanges between the artisans, all learning from one another. It is all about transmission, honouring traditional skills while also innovating with process.

Your recent Fieldworks exhibition has been widely praised, both in Marrakesh and Miami. What is the show about and what themes do you explore within it?

I wanted to weave together Moroccan craft knowledge and traditions with the human and social narratives that sustain them. It is a dialogue between tradition and contemporary art, exploring issues of identity, community and transformation. So, for Fieldworks, I constructed and built experiences with artisans in different regions of Morocco, a constellation of experiments that were constantly renewed and evolving. All of the pieces in Fieldworks have this in common, with each work resonating as an echo of collected stories, mastered materials and traversed landscapes.

Through various techniques, materials and scales, I wanted to offer an immersive look into the research, experimentation and the power of collective craftsmanship that inform my approach. As my curator Meriem Berrada so beautifully put it, this exhibition is a manifesto for the preservation and reinvention of traditional skills and savoir-faire, bringing together the past and the future, memory and modernity, while simultaneously presenting art as a personal quest and a collective commitment. It is an environment where tradition and innovation coexist in a state of harmony.

Which particular artworks in Fieldworks exemplify your approach?

Especially interesting is an experiment that resulted in Bestiaire,a collection of six works that were shown at Loft Art Gallery in 2024.It consists of structures of functional objects that have been reimagined as three-dimensional looms. I often use architectural principles as a basis for my thinking and creative process – the line, the plane and the volume. When I was doing workshops with artisan weavers about ten years ago, I started looking at the loom, a two-dimensional object. For the series, I began to focus on the carcasses of chairs, stools and display structures. After many exchanges with the artisans, the process of weaving directly on the object started. They mounted the weft thread on the structures and proceeded to weave knotted surfaces with natural spun wool. Breaking the boundaries of tradition by weaving on an unfixed object necessitates bodily interaction with this new form of loom, using all its sides, exploring void and volume and sculpting with thread. They were as curious as I was about the outcome. This is what I love about the participatory approach – the artisans are willing to experiment with me.

You’re also exhibiting works at the recently reopened MACAAL.What can you tell us about those pieces?

In the context of the wider MACAAL show, The Garden Inside (2020) is a great example of how I use modules in my artworks. In my earlier work, I was terrified of colour. My mom, who is a painter, went into the garden. She cut all these leaves, gave them to me and said: “This is your palette”. That is a very important link to have with that installation. This is the landscape, or an imaginary utopian city, and it’s based – again – on architectural principles. Every piece is a line, created with a galvanized metal rod, rolled in wool and then sewn together, becoming a plane that is then shaped into volumes, and then the volumes become structures. The spaces between are like miniature pathways, seen from above. But what I really like is that everybody can be part of this act of transmission. If a piece falls, it can be reset, and I don’t have to be here to reset it. Everybody can participate in it.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue