Shaped by collective histories and political upheaval, the artist situates human resilience in expansive landscapes that serve as backdrops for resistance.

Canvas: Your work often explores themes of power, violence and control. What draws you to these subjects?

Amirhossein Bayani: My intellectual projects have always been about politics – not in the sense of power, but politics in the sense of emancipation. I was born an artist in the Middle East, in Iran, one of the most politically charged places in the region. Almost as soon asI was born, the revolution happened. I still vividly remember, as a small child, falling asleep on my parents’ laps while they and other family members discussed politics passionately late into the night, carried away by the fervour and chaos of those revolutionary days.

Then came the war. For eight years, my country was engulfed by conflict. I remember the sound of air-raid sirens, running to shelters, the fear of missile attacks and the loss of people around us – friends, relatives, neighbours. Even after the war, the same ideological structure continued. Repression, censorship and humiliation all shaped a painful social atmosphere that deeply affected my consciousness. Over time, through the books I read, I came to realise that all this suffering, both mine and that of my generation, stemmed from the way, society had been forced to confront the concept of politics itself.

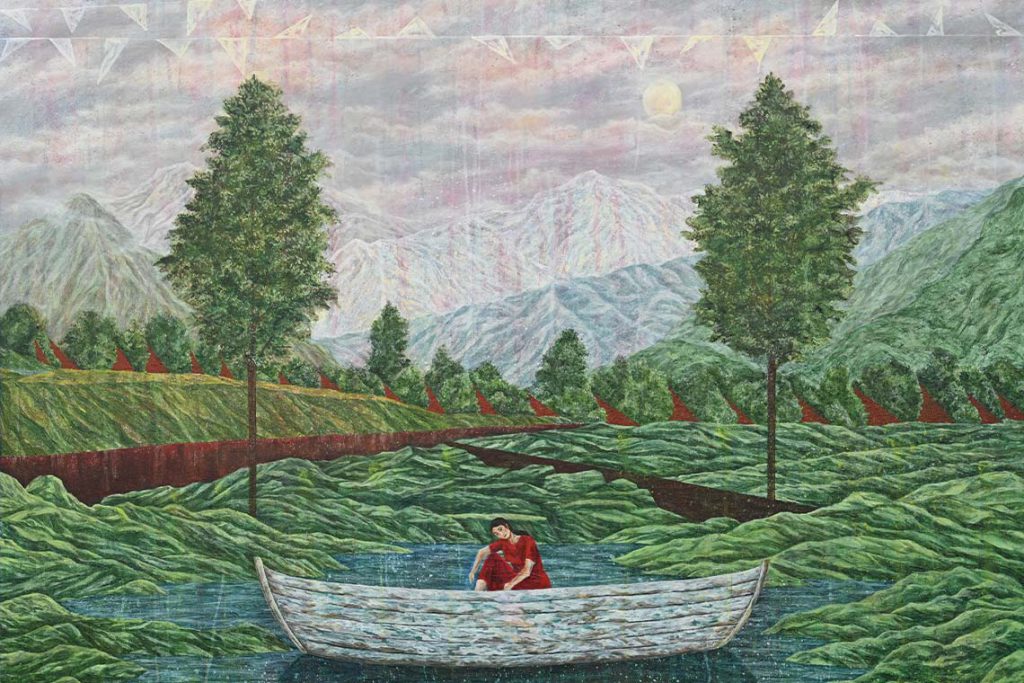

In your recent show, The Narrative of Minorities at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, one of the featured series was Wandering Toward the Meaning of Home (2025). How does this series reflect your thoughts on migration?

I think migration can take two very different forms. In one sense, someone might move from, say, the Netherlands to Sweden, simply seeking a new experience – this kind of migration is quite common. But there are also political or forced migrations, and especially in our region we are very familiar with that. When you are forced to migrate, you lose almost everything – your roots, language, culture, income, the life you had built. I think many migrants deeply understand this feeling. Even after years of living somewhere, they may still feel disconnected from the place they live in.

I’ve also been reflecting on the idea of ‘home’. As a migrant, you may have a house, you may even start to succeed and build connections, but even so, your sense of home might appear elsewhere – perhaps in a quiet corner of a metro station where you have your coffee and feel at peace, or in a small corner of a library. These can be the places where you reconnect with your roots, even briefly. Being in search of the meaning of home is an essential and profound experience for every migrant. That’s what I’ve tried to explore in this series.

Can you talk about your choice of using wood to create three-dimensional forms?

I genuinely love working on wood. I don’t get that same feeling when I work on canvas, although I often have to use canvas, especially for larger works, because wood can become very heavy and difficult to transport, and there are some technical limitations as well. Working with wood also allows me to explore different forms more freely. Of course, you can also do that on canvas but with wood it feels much easier and more natural. That sense of freedom and connection to the material really shapes how the forms emerge in this series.

How do you approach time in your work? Do you think it leaves visible traces that can be replicated in art?

Time is essentially a conceptual construct, an abstract notion that possesses no inherent quality or sensibility to exert a specific effect on anything. However, if we approach time as history, its nature transforms entirely. History becomes a vessel into which all human and natural experiences, ontological or otherwise, are poured. Within this vessel, these experiences interact, mutually influence one another and leave traces upon each other. It is precisely from this conception – history as a structuring container – that the notion of politics emerges and, through this historically informed politics, all human and natural experiences are organised and given form.

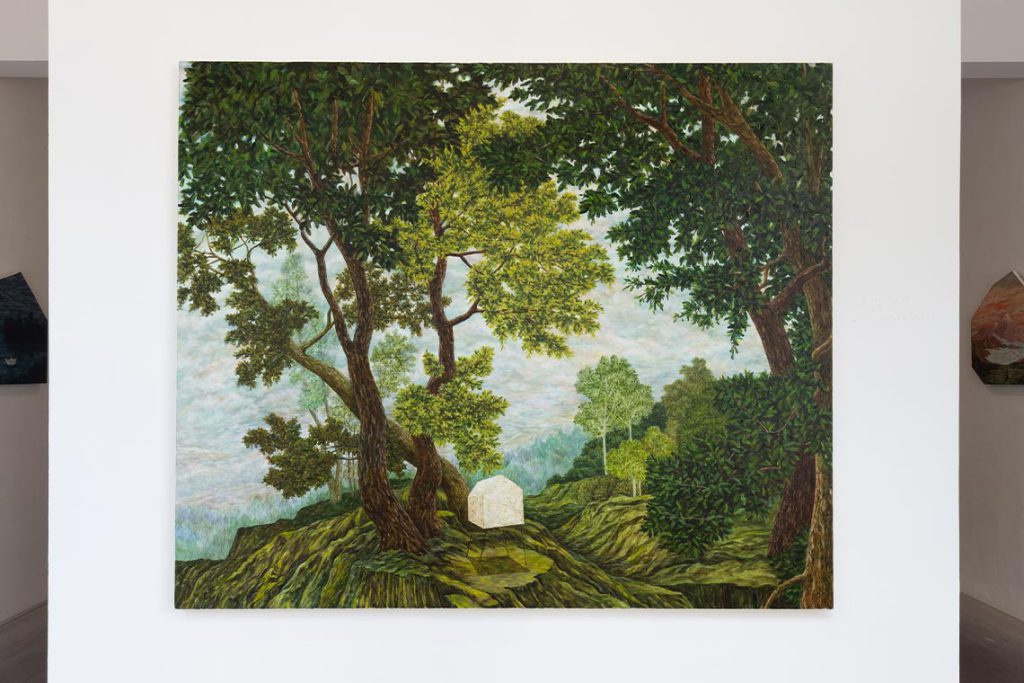

In your series The Season of Ruin’s Remembrance (2023), figurative statues are positioned in natural landscapes. What presence are they meant to have?

The statues function primarily as a symbol or monument. Many of them are directly inspired by real people and events in the history of Iran, so they have very concrete roots in my society. Yet, I deliberately refrained from specifying names or particular incidents because I felt that reducing the work to one person or a few individuals would diminish the universality of the subject. These works emerged after the protest movement later known as Women, Life, Freedom. They are a tribute to the unparalleled courage and indefinable bravery of the young women and men of my country who have fought to claim their rights. By placing these monuments within natural landscapes, I aimed to honour them while also situating their struggles in a broader, almost universal context. I also wanted to create a space of possibility, where the figures – like nature itself – can be both passive and active, calm and forceful, beautiful and formidable. They become a reflection of political and human potential, a symbolic presence that resonates with the complex interplay of vulnerability, strength and agency.

How do you approach painting nature as both a place of beauty and a space marked by violence or loss?

Nature constantly contains strange dualities – in fact, it’s always a set of binary oppositions and those are precisely what give it the potential and capacity to serve as an unrivalled model for any imagination, presentation or statement. Nature is at once passive and active, at once a bearer of lack and a narrator of excess and surplus. Nature is the ground of mind. When I speak of the human as a subject – I mean the mind – you simply can’t conceive of any horizon that lies outside nature. We must remember not to turn nature into a fashion or a hackneyed trend that is used superficially. Nature always carries many binary tensions; it can be profoundly complex and it can also be banal.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 120: The Traces Left