Filled with contemporary metaphors and symbols from the past, the paintings of Anuar Khalifi explore issues of identity, society and tradition fused with modernity. Now, after a year in which the world came to a halt, Khalifi discusses his process, his concerns with labels and what is next for him in uncertain times.

It’s a warm spring day in Barcelona when I Zoom with Anuar Khalifi. “I’m feeling a little bit dizzy,” he laughs, gesturing in the air. He’s sat in his studio, sunlight streaming in through the window, with glimpses of his new works revealing themselves behind him. For the selftaught artist, who divides his time between Spain and Morocco, the limitations on travel are getting to him. “I was going to Morocco this week, but they closed the borders again,” he explains. “I’ve already been twice this year. It’s important for me to come and go, because when I come back to Spain, I can digest my ideas and my work is enriched when I see Morocco from a distance. Even though I isolate myself when I paint, I still need to be informed by the world, and being informed through a screen is not enough for me.”

Although he’s been drawing for as long as he can remember, Khalifi only started taking painting seriously around the age of 28. “I say to people, if you want to make yourself sad, then be a painter, or if you have things on your mind and you want to express them with your own hands,” he muses. For the artist, the process of creating a painting is an emotive and important autobiographical journey – “I paint for myself and try to kill my monsters there, so I don’t hide anything in the shadows or cover invisible things with paint” – and Khalifi’s colourful figurative works are indeed devoid of excessive shading or shadows. “I don’t like painting with shadow and if you can relate to an image that is finite and plain, it’s kind of amazing.”

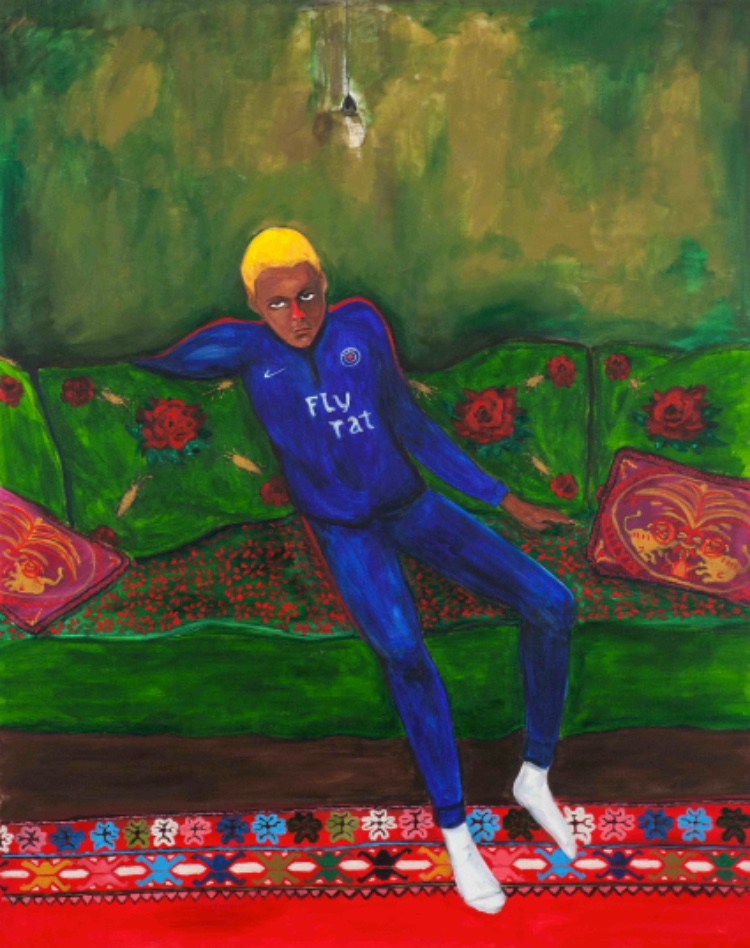

For Khalifi, the monsters he speaks of are wide-ranging and navigate complex social discourse and conflict between tradition and modernity. I first came across his paintings at the end of 2019 at his first solo show in Dubai, Forever Is A Current Event, at The Third Line, with the exhibition title taken from lyrics by his collaborator and friend, musician Yasiin Bey. Khalifi’s paintings, such as the triptych The Negus Asked Me “Do you want to be the Sultan or Rumi? And Then We Opened A Pomegranate (2019) or Dust Makers (2019) evoke clear symbols from his heritage and open the floor to dialogue about identity through his not-so-subtle references. Each image is filled with historical meaning, as he notes: “There’s an Arabic phrase that says ‘meaning precedes form’ and I think that’s the idea of life and art. Everything has a meaning, every colour, every circle and how you paint it.”

Meanwhile, the notion of identity cannot be shaken from his work. “I am in total resistance to saying what my identity is, because I don’t know,” he affirms. “But I am interested, so I go back to search. It informs me, but I am not painting because of my background. I am a painter and my life informs me, and when you paint you have your tools. Life experience is one of them. I embrace my identity, which I know is a conflict many diasporic immigrants have.” He goes on to tell me a story about finding an old photograph, taken in an Arab country, when he was a kid and the romanticism of identity. “You can grasp that something is lost there…” he trails off.

Khalifi’s work is constantly evolving, becoming more tightly and confidently honed. “At the beginning, my painting was more aggressive and violent in some ways, with a lot of information put together,” he recalls. “But each time, it’s becoming more focused. I think every painter tries to say the most important things simply and put meaning to things from their own perspective… Painting captivates the here and now, and as a painter you have to be honest with yourself.”

Around the same time as his Dubai solo show, Khalifi’s painting Roses & Cockroaches (2018) was acquired by the Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden (MACAAL) in Marrakech. “I am super proud and have always been interested in African art. I remember my first visit to MACAAL, a year before they acquired my painting. It was one of the first times that I felt like I was proud of something. It’s vibrant what is happening in Africa. The knowledge and the traditions have always been there, they’re not anything new, but we do need a platform like MACAAL and I am super happy to be acquired by it.”

For Khalifi, with identity so imprecise and undefined, problems understandably arise when others are quick to categorise. “I am an African artist, I am an Arab artist, I am ok with that. To be part-Muslim or part-European, it doesn’t have to sound weird to say,” he continues. “But you want to be recognised as an artist without an adjective and when a gallery outside focuses on my work as an ‘African’ artist, I feel a bit uncomfortable. We need to do our own stuff and one of the things I deal with through my paintings is going to museums and not seeing people who relate to me. I think this is something all figurative painters from Africa struggle with.” An example that sticks out for Khalifi arises from his frequent visits to the Museo del Prado in Madrid. Although he is a fan of Francisco Goya, and references him twice in our conversation, he always pauses in front of The Second of May 1808 (The Charge of the Mamelukes) (1814), no matter how many times he’s seen it. “You see the French troops and then you see the Muslims are cut in half,” he says. “That painting has always been on my mind.”

What’s next for Khalifi is a series of exhibitions taking place around the world and online. He was featured in The Third Line’s recent Yasiin Bey exhibition and is currently part of Paris’s National Museum of the History of Immigration exhibition, What is forgotten and what remains (runs until 29 Aug 2021), in collaboration with MACAAL and including works by 18 artists from the African continent and its diasporas. Other plans are in the pipeline, but will depend on the current pandemic situation, which has also forced his work online. As with most things in the digital realm nowadays, there is no escaping NFT talk. “I’m still struggling to do online shows,” Khalifi admits. “I have a new piece that’s three metres wide, so to show it in an online show without interacting…” He looks frustrated. “I want to see it somewhere because I need it to breathe. Any painting changes once it leaves the studio door, so to imagine it just being an NFT…” he went on. “You smell the painting, you get mad, you get happy, that moment is captured there in the painting and someone needs to see that with their own eyes. You can’t evaluate a work of art without seeing it in person.” It is clear from our conversation that tradition, identity and society provide the backbone of his work, but for Khalifi, painting is more about the process, a reflection of the current moment and a search for answers. “We are acting as if everything is new, but there is nothing new,” he says. “We have the same experiences as human beings and the essential things have always been there.” So, try to pigeonhole him all you might, but Anuar Khalifi is purely an artist (with no additional adjectives), attempting to capture the here and now.