Ever mindful of the power of storytelling, the artist stitches memories and experiences in works that transcend time and place.

Unlike paintings or sculptures, which sit in the rarified realm of the museum, textiles have an intimate connection with our lives. They are used for self-expression or ceremonial rituals, but we also rely on them for everyday practical purposes. Take a simple shoe, for example. “The object itself is laden with history,” according to British-Lebanese artist Aya Haidar. “A foot has rubbed on the sole of that shoe every time it’s taken a step.” What kind of stories are told by those traces left behind? This is the question Haidar has been asking since 2018 with the artistic project Soleless, which takes old shoes worn by displaced people on migratory journeys and embroiders them with the wearer’s personal accounts of loss, separation and survival.

The idea evolved from the Deveron Project residency, which sent Haidar and anthropologist Marc Higgin to help integrate 120 Syrian refugees into a small village in rural Aberdeenshire, Scotland during the harsh winter of 2017. To help foster a sense of community, the pair set up a café serving Syrian food to locals and Haidar, one of the few Arabic speakers, took the opportunity to learn more about the new arrivals. “They had absolutely harrowing stories, but they needed to be told,” she says, referring to accounts of grieving mothers, separated families and abuses perpetrated by the Syrian army. Haidar saw how easily these stories, which were almost too traumatic to recount, could be forgotten. So she vowed to make a record.

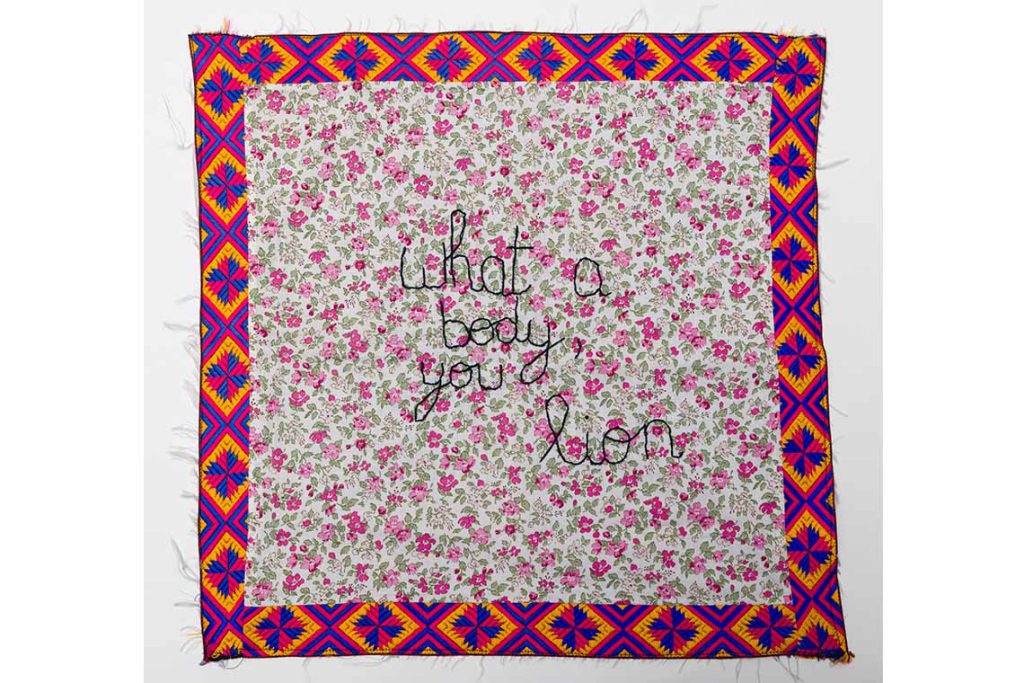

Aya Haidar. شو هالجسد يا اسد from the Tolteesh series. 2019. Embroidery on cotton. 57.5 x 58 x 5 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Tabari Artspace

A sense of urgency and responsibility to preserve these histories defines much of Haidar’s work. Born in 1985 in the USA to parents who had fled Lebanon, she was brought up in Saudi Arabia until the age of six, when her family settled in London. Haidar recalls speaking Arabic at home and taking annual trips back to Lebanon each summer, causing her to wonder why her parents had left. “So many conversations I had with my grandmother and mother growing up retraced that generational narrative, learning which uncles and aunts left or stayed and why,” she says. “The traces of war are so apparent in Lebanon. You cannot walk down the street without seeing bullet holes in the walls. There’s always a threat, whether a car bomb or someone who got assassinated, at the forefront of our minds.”

Haidar asked questions about the past during weekends spent at her grandmother’s house. She would be given a needle and thread and taught to darn while listening, a custom that she only years later realised is age-old. “Now that I look back at the history of women and craft, I see how because of my grandmother’s age, because of her generation, the act of making collectively as women is something that she grew up with. It’s a language she understood,” Haidar recalls. “Our hands always had to be busy. So much of my heritage was unpacked in the making.” When Haidar was older, she began making rag dolls.

At school, the French Lycée in London, Haidar spent all her breaks in the art rooms. “I found it such an amazing outlet to be able to make something where there was no right or wrong. That was the language that I understood.” Unfortunately, the only medium offered was painting. “It was very draconian, there was absolutely no place for creative thinking whatsoever,” she says. Nonetheless, a foundation year at Chelsea College of Arts confirmed her burgeoning artistic interests. In 2004 she began a BA in painting at the Slade, but it would not be until her third year, while studying abroad at the School of the Art Institute, Chicago, that she found the Fiber and Material Studies Department. “I saw how conceptual art can marry into textiles,” she says. “I thought, this could get political.”

Image courtesy of the artist and Cromwell Place

Conversations with Haidar’s grandmother about her family’s past in Lebanon came flooding back and inspired the large patchwork tent that she made for her degree show from old clothes with a woven ground. The inside walls and cushions were embroidered with personal, painful stories of forced migration. “I put my heart and soul into it,” she recalls, but was then shocked to find the work dismissed by her classmates. “I got comments like, why is that important? How is Lebanon relevant? What’s the point in making political work? I remember feeling so distraught.” One peer even suggested that Haidar leave art school and apply for an MA at the London School of Economics. She already had a place when the gallery Bischoff/Weiss got in touch, having found her tent “so subtle and poetic”. They waited for Haidar to finish her MA and, shortly after graduating, she had first solo show at the gallery. “If they hadn’t injected me with self-belief, I don’t know if that’s the trajectory I would have gone down,” she says. “They saved me.”

In recent years, Haidar has worked on projects like Tolteesh (2019), in which classic catcalls like “you’re edible without salt” and “your height is like a fava bean pod” sound cheesy but romantic in Arabic, but when translated into English suddenly become absurd. “It’s a humorous entry point to talk about the objectification of women,” says Haidar. “The works are very unassuming, but when you look closer they’re a bit darker.”

Women’s experiences were also addressed by Highly Strung (2020), a response to the observation that during lockdown Haidar took on more domestic labour than her husband, who works a typical 9 to 5 day. “What happened to our equal share?” she wondered. “I was wiping snotty noses or renewing the library books or cleaning the kitchen or making beds.” Each day for a year she isolated a single invisible chore and stitched it onto an old dish rag or a Babygro. The 365 items were hung on a clothes line and collectively priced at minimum wage for someone working all day, every day, for one year. “It’s a commentary on the relentlessness of womens’ labour,” says Haidar. “There isn’t clocking on and off, especially if you’ve got kids.” The piece is now part of the permanent collection at Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, which Haidar believes is “a very interesting context to talk about domesticity and invisible labour. The aim of my work is to create arenas for discussion.”

Another series Safe Space (2023), included in the recent exhibition Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery at The Whitworth in Manchester (see page 90), was inspired by watching footage of a friend barely surviving the Beirut explosion in 2020. Haidar reflected on how people live in war zones. What are the small acts that allow them some degree of control or safety? She began illustrating her mother’s childhood experiences, from sleeping under the bed during bombing raids to wearing pots to protect her head from flying shrapnel. Understanding something of this day-to-day existence helped humanise an otherwise unimaginable situation. “I’m not going to be able to relate to someone in Gaza living under bombing and shelling,” explains Haidar, “but I’m going to be able to relate to a mother trying to calm down her child who’s hungry.”

In early October, Haidar will unveil a large public light installation commissioned by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, a project which emerged from several workshops with the Geezers, a group of old men who grew up in the area of Whitechapel in East London. The aim is to preserve a part of the area’s cultural heritage, in this case the dying tradition of Cockney rhyming slang. True to form, Haidar is inventing a new verse, but one that will be woven through with that community’s deeply personal memories.