Unremittingly focused on what it means to belong, the artist strives to investigate the power of individual geographies.

The works of Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili have been sparkling across the world for years, showing up in galleries, fairs and biennials with the depth and speed of a diaspora in dispersal. Even as I converse with her via email, she and her works are in constant movement, busy with the opening of a solo show, Between Circles and Constellations, at MACBA in Barcelona. Co-produced with the Sharjah Art Foundation, the exhibition marks the European premiere of Khalili’s latest work, a mixed-media installation entitled The Circle (2023). It explores “a forgotten historical event: the candidacy of an undocumented Maghrebi worker in the 1974 French presidential election,” the artist shares, and is “essentially a meditation through oral poetry and performance on the notion of belonging and community”.

The Circle recently won Khalili the prestigious Sharjah Biennial 15 prize. Her CV – the size of a scroll-like receipt for a massive grocery run – boasts countless solo and group shows and other accolades: Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute Fellowship, documenta 14, the Venice Biennale, the SAM Art Prize, the Abraaj Group Art Prize and more. Along with another artistic powerhouse, Yto Barrada, Khalili is also a founding member of the iconic Cinémathèque de Tanger in Tangier.

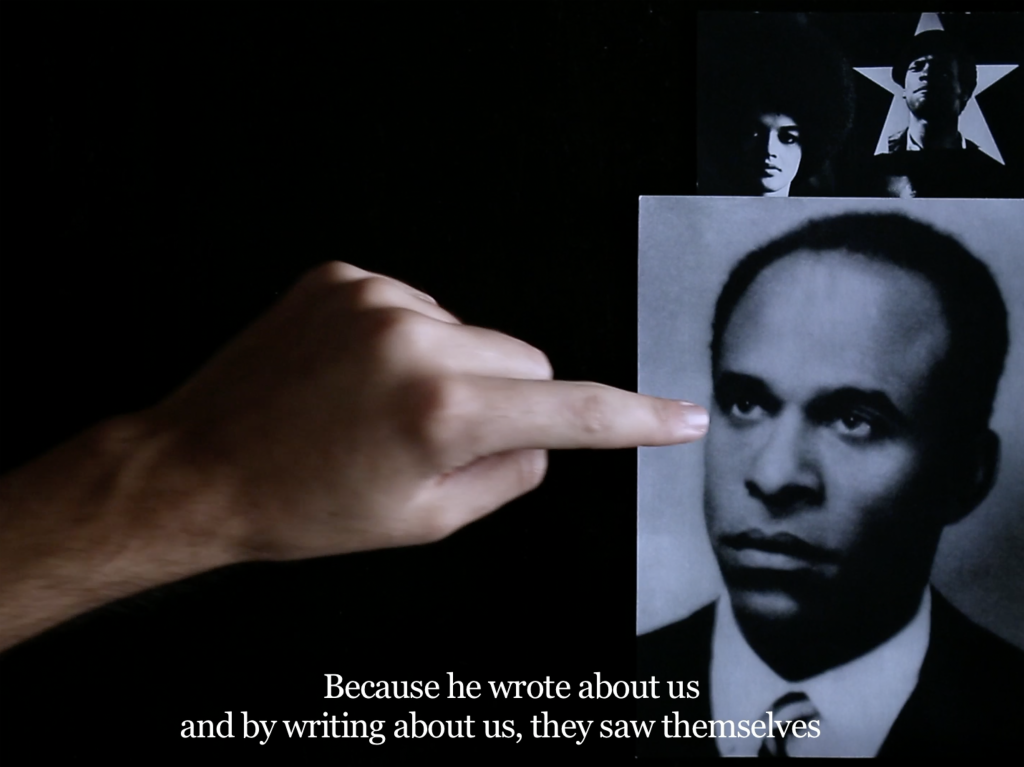

For an artist with a dual background and an expansive, meticulously researched practice that often explores imperial and revolutionary legacies, Khalili resists seeing her work “as a practice on migration, or colonial and post-colonial history.” She insists, instead, that audiences and critics like myself reorient our perhaps knee-jerk responses to such topics, where our eyes only scale the surface of the past and elide the present and future. Khalili’s 2015 digital film Foreign Office, for instance, focuses on 1962–72 Algiers, which became, in the words of Guinean leader Amilcar Cabral, a “mecca for revolutionaries”, hosting representations from Global South liberation movements like Nelson Mandela’s ANC and the Black Panther Party. But the film is not steeped in this history as much as it is in historiography and its malleability. Portraying two young Algerians “rewriting” this time period through “cinematic montage”, Foreign Office certainly drops into a less-highlighted era, but it is not stationarily positioned there. Rather, it is invested in transforming a forgotten segment of the past into a figment of the present, transmitted forwards into futurity by fresh-eyed youth. In doing so, Khalili also depicts liberation as inextricably entwined with poetry, language and orality.

Khalili was born in 1975 in Casablanca, where she spent her childhood, before being later raised between her birthplace and Paris. From France and Morocco, she inherits double, interlinked histories, both sides of the coins of colonisation and immigration. Over time, she has gathered more cities and histories into the folds of her life. After studying film and media studies at the Sorbonne Nouvelle, and visual arts at the École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Paris-Cergy, Khalili was invited by DAAD in 2012 for a residency in Berlin and ended up staying. Later, she made Oslo another base, becoming a professor at Norway’s National Art Academy. She is now a Professor of Artistic Strategies at Vienna’s Angewandte University.

The core question that has animated Khalili’s practice from the start has been: “How can we form truly inclusive communities?” It’s a conceptual drive close to philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah’s notion of cosmopolitanism, which asks how people of different histories and presents are able to live together in harmony while maintaining their difference. “From the first day of my education at the School of Fine Arts in Paris,” Khalili recalls, “I started producing works in film, video, photography and prints in collaboration with members of communities excluded from the right to citizen membership.” In her work, Khalili sutures together marginalised elements of history and the people that have carried them and will continue to carry them forward, in order to build answers towards how radical inclusivity, the truest freedom, may manifest itself. “All of my works are connected to each other through the very question that has been haunting my practice from the beginning,” she explains. “How can we rethink forms of belonging freed from restrictive conceptions of identity?”

In her eight-channel video installation The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), various individuals who have crossed borders illegally partake in “an alternative practice of map-making”. One long static shot in each video focuses on a participant’s hand wielding a permanent marker to draw the intricate webbing of roads used for such illegal crossings direct onto a map. In the background, the participant’s voice narrates the details of their journey. One of these is of a young man from Ramallah who cannot freely visit the woman he loves in East Jerusalem. Cinephiles might recognise a similar storyline from Palestinian director Elia Suleiman’s 2002 film Divine Intervention. Obstructed by the Israeli occupation, a journey that should have taken a short car ride now involves a whole day of walking, climbing hills, hiding from the military and risking his life. This installation, at first, seems like a tracing of the topographies of trauma, but instead reveals the arbitrary fragility of maps and the nation-state – not dissimilar to Shilpa Gupta’s 100 hand-drawn maps of my country (2008–ongoing). It also shakes the ground out from beneath the rigid idea of what a citizen – with or without a state – might actually be, especially in terms of the lines they cannot cross and the areas they must be penned within. When starting from the question of how to loosen forms of belonging from constrained concepts of identity, Khalili asserts that her works actually convey a sense of hope. “Each of the videos [from The Mapping Journey Project] ends similarly,” she says, “with participants projecting themselves into a ‘becoming-citizen’.”

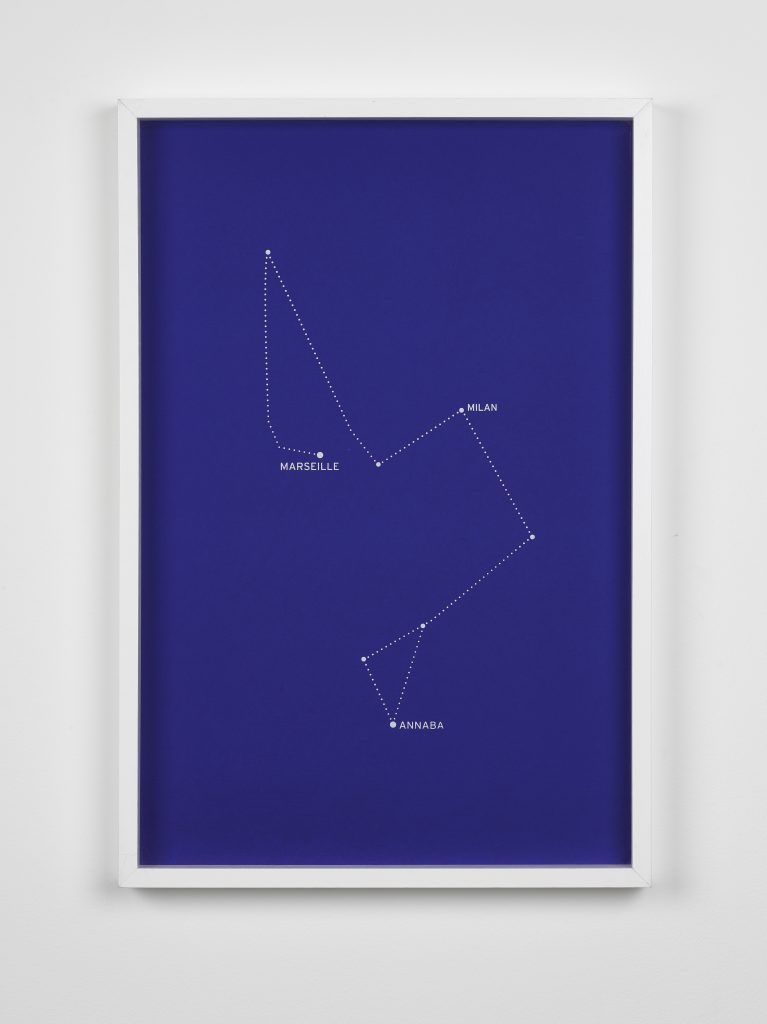

Another work, entitled The Constellations (2011) and consisting of eight silkscreen prints on paper, dislocates our traditional ways of viewing world geography. It begins by first situating itself with the positional lenses of “those who are excluded from the right to mobility”, becoming a poetic meditation on French writer Édouard Glissant’s notion of the “All World”. Even The Mapping Journey Project embodies Glissant’s idea of “opacity”. It lets its subject-participants remain rather opaque, something that Khalili believes every person has a right to do. “I believe that respecting the ‘opacity’ of otherness opens up to a decolonised conception of universality,” she stated in a 2019 interview for Berlin Art Link.

Khalili’s decades-long career has seen her evolve into a more complex figure than simply just an artist. She not only represents different narratives but also arranges them symphonically in order to orchestrate alternative sites of knowledge perception and production. Again and again, she attempts newer forms of “imagined communities” and of what she calls “radical citizenship”. Looking back at the 20 years since her first participation in an exhibition, she says how she remains “attached to the Maghrebi tradition of the public storyteller, mixing genres, languages, time and space, so that an audience can form a community brought together by the very act of storytelling.” Her self-description sounds similar to what the postcolonial feminist scholar Madina Tlostanova terms the “transcultural trickster”, who uses creative techniques such as manipulation and bricolage to subvert existing power structures. At a time when nationalism and racism are soaring worldwide, Khalili’s work is certainly that hackneyed yet crystally accurate word – urgent.