Celebrating the birth of Moroccan contemporary art, The Casablanca Art School exhibition at Tate St Ives reveals the colourful innovation of a glorious era in the country’s artistic history.

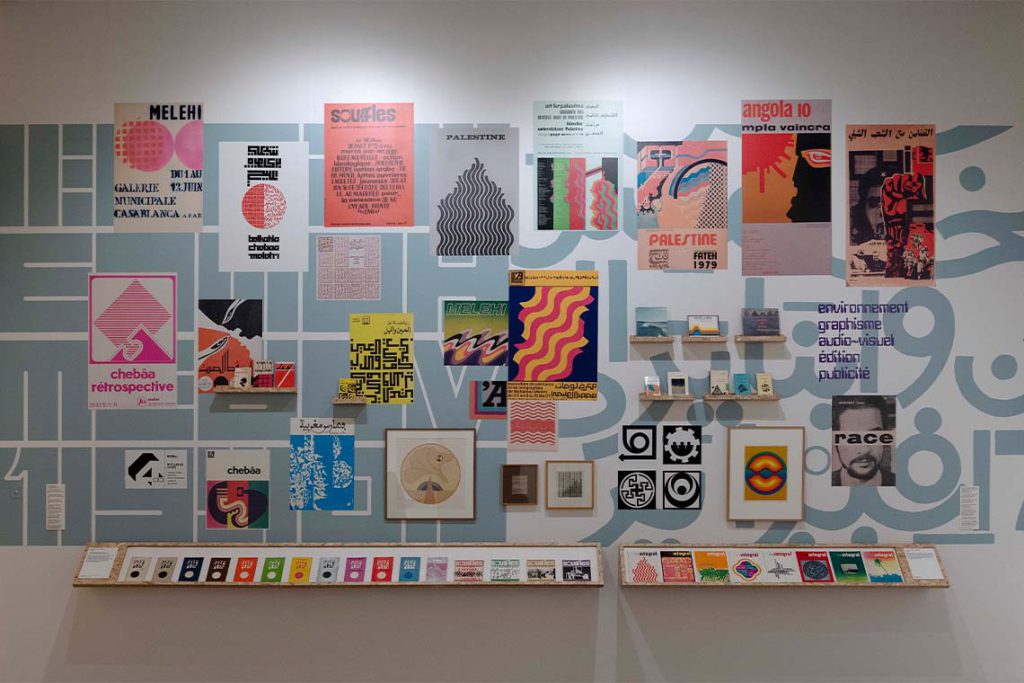

Once in a while there is an exhibition that is so vibrant and multi-layered that it offers endless avenues for discussion and interpretation. The Casablanca Art School show at the Tate Gallery in St Ives is one such case. Curated by Morad Montazami and Madeleine de Colnet, with Anne Barlow, director of Tate St Ives, this exhibition is bursting with colour, paintings, ceramics, all manner of video footage, posters, books and archival material, as well as architectural models, carpets, decorative wooden beams and Arabic calligraphy.

Set in Tate St Ives’ vast new exhibition spaces, completed in 2017, the show brings together a range of around 600 works by 22 artists associated with the Casablanca Art School (CAS). It focuses particularly on three figures, whose works Montazami bookmarks in the entrance space of the exhibition: Mohammed Chabâa, Mohamed Melehi and Farid Belkahia, who was also the director of the school between 1962 and 1974.

In a celebration of the birth of contemporary art from Morocco, the exhibition first charts the state of art teaching at the CAS prior to 1962, when it was very much a colonial outpost of the Paris Ecole des Beaux Arts, and then looks at Belkahia’s modern, ‘new wave’ approach. During this period the CAS broke free from its colonial heritage and began to accept both Moroccan nationals and female students – which had not been the case during the era of elitist French rule – and embrace a more inclusive approach to the arts and a shift away from traditional Western art teaching.

Not unlike the German Bauhausschool of the early 20th century, the CAS taught students fine art as well as art history, drawing, painting, graphic design, installation work, photography and architecture. A beautiful ceramic arrangement by Abderrahman Rahoule, set against a vibrant painted background at the entrance of the exhibition, underlines the significance of this approach.

The CAS led the country’s modernist movement and it was responsible for Morocco’s first outdoor art exhibition, Presence Plastique, in 1969. Part of the school’s mission was to bring art to the public, which in this case involved paintings and large textile works being hung or slung over walls or poles in the popular Place Jemaa el–Fnaa in Marrakesh in a public art intervention designed to spark conversations and get people thinking about art, artists and artistic production. A screen in the second gallery shows original footage from the 1969 event, which gives the exhibition a welcome sense of documentary reality as the curiosity and interest of the passers-by is captured on film.

Although craftspeople and artisans have long occupied an important role in Moroccan daily and domestic life, the artist’s role in society was not widely discussed and there was not a popular or contemporary gallery ‘scene’ as such. The CAS wanted to emphasise the importance of art in society and also recognise the value of artists and art historians as sharers of knowledge, ideas and creativity. This form of public engagement broke with previous notions of art belonging in specialist schools or elite studio spaces and marked a shift in approach that was to gain the CAS many new followers and enhanced attention.

One room in the exhibition highlights the contribution of Dutch linguist and anthropologist Bert Flint, who taught art history at the CAS. From 1957 onwards he travelled around Morocco and other parts of North and West Africa, researching aspects of African culture and Amazigh (indigenous Moroccan) weaving, painting, hairstyles, tattoos and ceramics. Flint was able to highlight to CAS students the vibrant visual culture in Africa at the time and teach them that their cultural roots came from this heritage and context.

Large photographs of Amazigh jewellery and carpets pick up on the abstract shapes in works by Chabâa and Melehi, as well as Malika Agueznay and other artists associated with the school. The emphasis on tribal jewellery and inclusion of artefacts alongside the paintings by CAS artists creates a great sense of continuity in the exhibition. It also reflects the ways in which tribal decorative objects and even Arabic calligraphy helped to inspire abstract and graphic art in the CAS. For example, a wall is covered in magazine cover designs for the Moroccan plastic art cultural journal Souffles,created by Abdellatif Laâbi in 1966. The stark shapes, strong lines and vibrant ice-cream colours have become characteristic of ‘sixties’ designs, the familiarity of these shapes helping to underline the importance of the CAS and its achievements.

The exhibition also focuses on the impact overseas of CAS artists such as Mustapha Hafid, Mohamed Hamidi and Abdelkrim Ghattas who, along with Melehi and Chabâa, represented Morocco at the First Biennale of Arab Art in Baghdad in 1974. Their presence highlighted Morocco’s position as a respected producer of contemporary art and doubtless helped secure their country’s nomination as host for the Second Biennale of Arab Art in 1976.

Two years later, Melehi was instrumental in co-founding an annual festival in the Northern Moroccan town of Asilah, as a way of inspiring tourism in the cooler months and also inspiring creativity in the young people and children of this dilapidated seaside town. The inclusion of photographs from the Asilah festival in the exhibition’s final room, with its painted murals, exhibitions and workshops originally led by Toni Maraini, a CAS teacher, points to the enduring legacy of the CAS in bringing art to the public. Festivals of this kind are also shared with towns such as St Ives, where the Tate exhibition is currently on show, and the historic centre of Sharjah, where it will travel to next.

The colourful Casablanca Art School exhibition is part of a collaborative project that includes KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, Germany, as well as Sharjah Art Foundation in the UAE and Goethe-Institut Marokko in Rabat, Morocco, as well as ThinkArt in Casablanca and Zamân Books in France. Such partnerships in the name of art are very much part of the CAS culture and legacy.