Meriem Bennani’s solo exhibition For My Best Family at Fondazione Prada brings together two works which explore the dynamics of conversation and collectivity in the human experience through installation and film.

The word ‘animation’ comes from the Latin animatio, meaning to ‘give life to’, to make something dynamic, in terms of breath and movement, and to establish dynamics. The principle, in technical and conceptual terms, unites the two works in For My Best Family, Meriem Bennani’s exhibition at Fondazione Prada, which opened on 31 October.

On the ground floor of the Fondazione’s Podium building, an archipelago of flip-flop mounted islands clatter, clang and clap in a “ballet-symphony-riot” of mechanical movements. Sole crushing, a kinetic installation by Bennani and musician Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner), makes rhythm with “the lowest shoe in the fashion chain”, balancing harmonious and seemingly chaotic sound through a meticulously engineered machine. The flip-flops strike and slap thanks to a pneumatic system of mechanical elements and compressed air, with sections shutting down when another group takes too much air — creating a sense of the islands being both in conversation with one another and mutually dependent in terms of function.

The work is inspired by rituals and folklore in Moroccan music culture, like the deqqa marrakchia, which is connected to religious incantation and African trance, a mystical form of music rooted in improvisation and collective experience. Sole crushing echoes the sounds and connected behaviours of celebratory gatherings and protest demonstrations, similar to the movement of bodies in a cathartic ritual. Observing the installation feels like being in among a scene from Fantasia —like when the brooms stand up and start marching with buckets of water in hand — or at the opera, admiring the skill of an orchestra.

Photography by Delfino Sisto Legnani–DSL Studio. Image courtesy of Fondazione Prada

In her introduction to the exhibition, Bennani said that while watching us interact with the installation for the first time, she had hoped that people would dance. Generally, she is most interested in people’s emotional responses — to her work, and within her work — and the moments when learnt behaviours and responses are overwhelmed by a desire to connect with our surroundings and each other. “A central theme of [the exhibition] is how to be together, questioning where we start and stop as people”, Bennani writes in the exhibition guide. “In the film, it is very much about a daughter and mother learning to be together — to really communicate — and the installation is a more abstracted idea of being together as a larger collective. Moments that are non-verbal, where it seems there is a force that takes the form of a multitudinous body.”

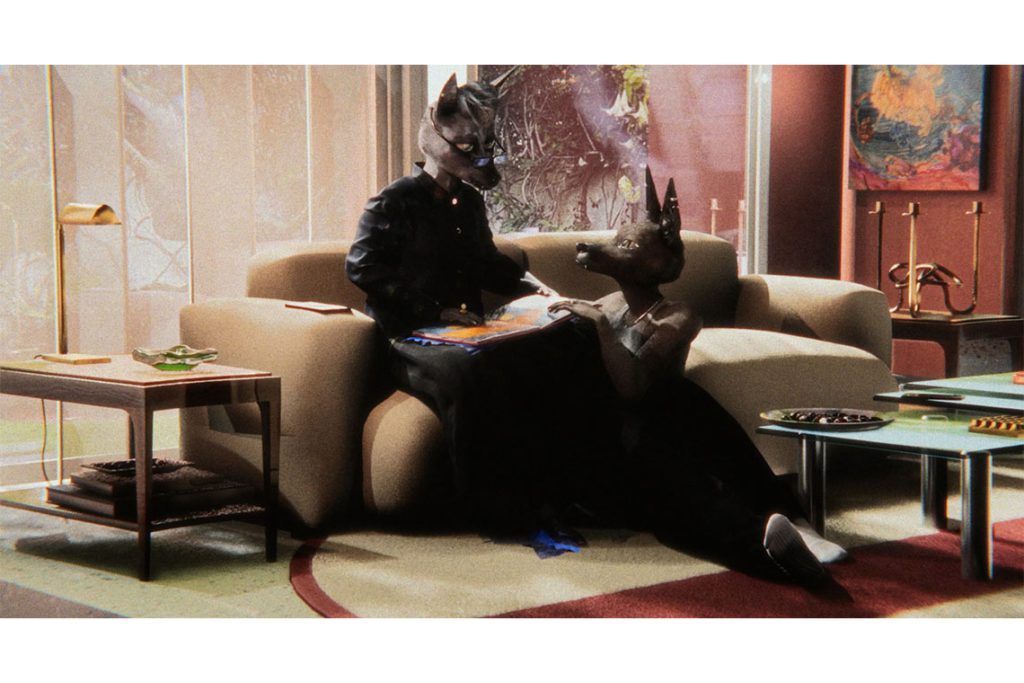

Upstairs in the Podium, the gallery has been turned into a free-standing cinema, glowing in the middle of an otherwise dark room. The screen, which faces a stack of moss-green velvet seats, shows For Aicha, an animated film about a Moroccan jackal who lives in New York. Bouchra — the jackal — is making a film about her relationship with her mother, a process that is also part of an effort to connect different parts of her identity. The film, and the film within the film, is framed around Bouchra’s conversations with her mother about the letter she sent her almost ten years prior, telling her about her sexuality and her experiences in New York, Rabat and Casablanca.

Co-directed by Bennani and Orian Barki, and made in collaboration with John Michael Boling and Jason Coombs, For Aicha manages to balance the visual integrity, and mind-boggling labour, of 3D animation with the incidental, lucked-out feeling of documentary filmmaking. The story, and its story-within-a-story, switches narrative and geographical contexts, moving between in-the-moment, recorded conversations and scripted, reenacted scenes. On first viewing, the film is confusing, maybe purposefully, with multiple versions of each character playing almost alongside each other. On the second, it feels like a true representation of difficult conversations with people we love, and the ways in which we can play them over in our heads many hours, weeks, months or years after the fact, as if a bird’s-eye view of our own life might help make sense of it.

Some of the most affecting scenes are the incidental, free-flowing moments between Bouchra and her friends — a cacophony of anthropomorphised animals — who jump between heavy conversations about romantic and familial dynamics and observations about “hating circles” in the way only true friends-like-family can. Many of these conversations arrived later in the process of making the film, as Bennani and her collaborators sought to bring the freshness and strangeness of human behaviour into the animation.

Bouchra’s conversations with her mother, where they cry and laugh together as they talk over the phone, also came later in the process of making For Aicha. “We realised through the process of making the film, that the character understanding her mother needed to happen in real life, as well as through the film that she is making in For Aicha”, Bennani says. Bouchra and her mother both want – and at some points struggle – to connect with each other in these scenes, both the recorded conversations from life and those written for the film. Bouchra is at her most vulnerable in these moments, moving with an eyes-watering swagger that belies the potential ferocity of her form. “This meta-narrative, of conversations with my mother, organically became the meta-narrative of the film,” Bennani says. “We have something that is so real, and yet we are animating animals. We can be very surreal, and just think about gorgeousness, and have the grounding of reality. There is a truth to some emotions that you can’t fake.”