Illuminating landmarks across the UAE capital – from its corniche and beaches to its mangroves and iconic buildings – the inaugural Manar Abu Dhabi casts a new light on how art can be experienced.

Amid the mangroves of Abu Dhabi, a carousel rises from the water. A chair, ladder, satellite dish and giraffe take the place of the usual leaping horses, their reflection cast onto the calm waters of a November night. This playful installation by Ayesha Hadhir, Rawda Al Ketbi and Shaikha Al Ketbi – part of their Dawaran (2023) trio of sculptures – is among the works commissioned for the inaugural edition of Manar Abu Dhabi, an expansive light art show that sees 35 site-specific light sculptures, projections and immersive artworks illuminate the unique landscape of the Emirati capital.

Manar is not a standalone venture, but rather a central component of Public Art Abu Dhabi, announced in spring 2023 by the city’s Department of Culture and Tourism. Although preceded by the unveiling of digital media work WAVE (2020/23) (by art collective d’strict) at the city’s Cultural Foundation, Manar – meaning “lighthouse” in Arabic – feels like the true spearhead of this far-reaching initiative, a beacon pointing ahead to Abu Dhabi’s inaugural public art biennial in 2024 and an annual public art investment to the tune of USD 35 million.

As befits its name, Manar welcomes Emirati and international artists – including from Argentina, Japan, Palestine and the UK – to, quite literally, light up Abu Dhabi. The show takes place across varied locations, from the well-trodden corniche to the biodiverse Eastern Mangroves, inviting participants to engage with the city as a canvas, as well as respond to the exhibition’s theme: Grounding Light.

The idea was to be “grounded through artworks that bring us together through the medium of light, a medium that is very universal and creates very immersive connections in its different forms,”says co-curator Alia Zaal Lootah. In speaking to artists, fellow co-curator Reem Fadda explains, the organisers’ very understanding of light – and its propensity to ground – took on new dimensions. “We realised a lot of artists were dealing with nature, sustainability, attention to people, interaction with community […] this is the light down here with us on Earth. So, ‘grounding light’ came to mean that which illuminates our path,” she says.

Although all are site-specific, a number of the artworks reflect explicitly on Abu Dhabi and Emirati heritage, grounding Manar not only in the landscape but in a specific cultural and historical context. Dubai- born artist Asma Belhamar’s Chasing the Dance of Alfay (2023) explores the experience of those who have grown up in the UAE against a transient backdrop of rapidly changing architecture, while Nujoom also from Dubai, brings Abu Dhabi’s seafaring heritage to the fore with her installation of traditional dhows.

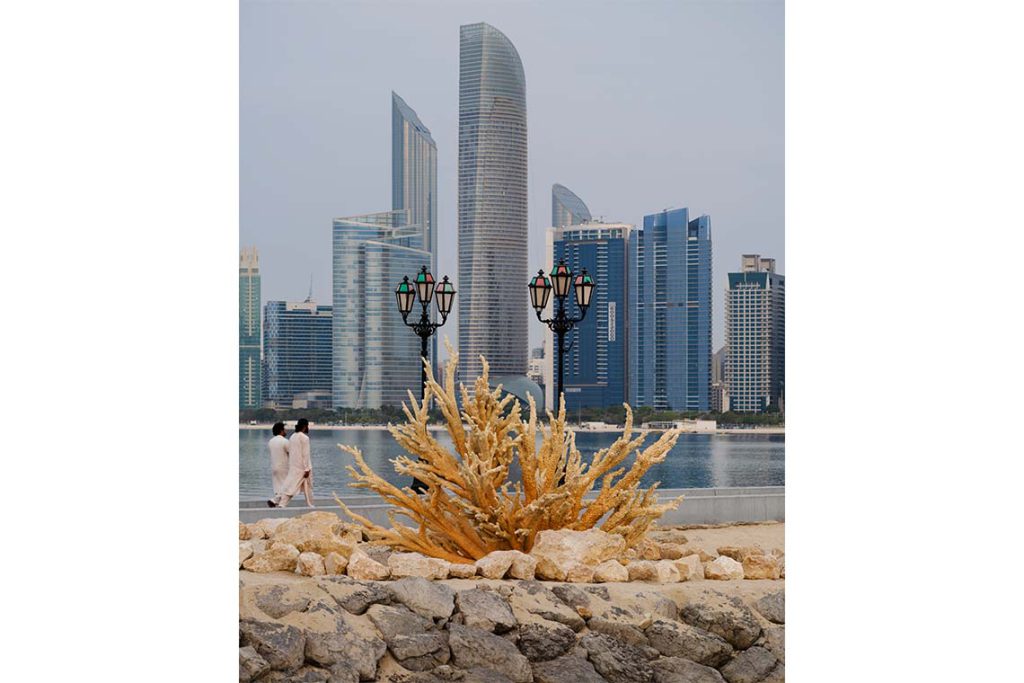

Even when exploring questions of global significance, most notably the climate crisis, artists – both Emirati and international – draw links between the universal and the local. Jumairy, who describes himself as a “Jumeirah kid”, tells Canvas how Manar saw him fall in love with the unique landscape of Abu Dhabi; his work Luciferin Shores (2023), founded on “understanding the landscape and sea level”, combines sound and light to foreground the beauty of Abu Dhabi’s bioluminescent beaches. British-Pakistani artist Shezad Dawood, too, in his Coral Alchemy (Acropora Grove) (2023) illustrates the human impact on the endemic Acropora downingi coral with a four-metre-tall sculpture, whose thermochromic paint finish changes colour with temperature fluctuation.

The primacy of context, however, is perhaps most striking in the organisers’ determination that the exhibition should engage a local audience. “It’s really for Abu Dhabi, our people and our community first and foremost. It means everything for us to serve our constituents,”says Fadda. Beyond simply placing the works in accessible locations and encouraging interactivity – Carsten Höller’s hilarity-inducing Abu Dhabi Dots (2023) game on the Corniche Beach being a prime example – this engagement extends to enlisting local volunteers in the very creation of some works. Jim Denevan’s colossal Self Similar (2023), an immersive land work comprising 448 sand pyramids illuminated by over a thousand solar lanterns, was realised in part by community members. “The community being there and connecting is powerful,” says Denevan, highlighting not only the interpersonal understanding forged, but also that between people and the land’s topography. “In some sense the artwork is an orienting device, both personally and community wide,” he explains.

Light, indeed, shows itself to be a grounding force throughout Manar, but this should not be confused with permanence or solidity. Instead, light casts itself onto and reframes surroundings, reforging the relationship between the viewer and their environment, eschewing familiarity, certainty and stability. Denevan’s pyramids, for example, are at the mercy of the elements and bound to shift or deteriorate, their imperfections accentuated by their luminous neighbours. “The work is grand at the same time as being vulnerable, and its completion is the point where it’s eroding and changing,” he reflects.

For Mexican-Canadian artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, such uncertainty and flux is not to be shied away from but inhabited as a space of possibility and connection. Taking over Abu Dhabi’s Al Lulu island, Lozano-Hemmer’s ten-artwork-strong Translation Island (2023) plays on the limits of human perception and potential misunderstanding.

Its component works include mammoth projected portraits of visitors’ faces, morphing into each other with the help of AI; a stream of poetry on which visitors must walk, constantly switching between languages; and 4000 lightbulbs, each pulsing according to the heartbeat of a different visitor.“We convene to understand one another, express ourselves, make meaning together, all the while finding both uncertainty and solace in that which remains untranslatable,” Lozano-Hemmer reflects.

“Unexpectedly confronted with the works in a natural setting, viewers are invited to interact with art beyond institutional walls,” says co-curator Lootah of public art. “What can we do as artists to make eccentric experiences, to interrupt the normal way in which we use public space and, more importantly, for people to come together?” Lozano-Hemmer ponders. In Manar, light has proven itself an apt medium to foster such “eccentric” experiences – its flair for unsettling, recasting and reinvigorating may not only apply to visitors’ relationships with their surroundings, but perhaps to their very conception of art itself.

Manar Abu Dhabi runs until 30 January 2024

This review first appeared in Canvas 111: Crafting the Contemporary