The latest edition of the Sharjah Biennial brings together a vast grouping of seemingly disparate works as it seeks to explore and explain the channels and sources of continuity in history and global dynamics.

Visiting the sprawling cultural odyssey that is the 16th Sharjah Biennial, the first question is likely to be one of where to begin, both in viewing and attempting to understand the exhibition. One place may be Joshua Segun-Lean’s essay, published in Frieze the week the biennial opened, questioning the contemporary biennial form itself. Market forces and other factors, he argues, have led to a mega-exhibition template in which the focus on expressing “art’s relationship to its social world draws attention to symptoms of structural failure rather than to the historical processes and power relations which gave rise to them.”

The works arranged in Sharjah, presented under the theme to carry, constitute an exhibition that appears to be altogether without a template – but also, with exceptions, free of what in Segun-Lean’s view are the sins of aestheticising the vulnerability of communities in crisis or histories at risk of being lost. Pushing past curatorial jargon and the challenge of spending time with a dizzying 650+ pieces of art, a good number of those works maintain discernible connections to the actual situations and communities that they represent.

Among the forms these connections take is that of carefully researched archival presentations examining how work from the past can be used to carry something forward from the past as the basis for action in the present. A collection of photographs from the first professional photography studio in Gaza forms a vivid portrait of the social, official and everyday aspects of life in the occupied territory. Assembled by Kegham Djeghalian Jr, the grandson of the studio’s founder, Kegham Djeghalian Sr, the archive constitutes Photo Kegham of Gaza: Unboxing – To Weave Unmade Histories and is the basis for the artist’s work to preserve Gaza’s precarious visual history. Studio portraits from the 1950s are accompanied by personal notes sent to the junior Djeghalian along with the photos. One of them, thanking him for “humanizing and depoliticizing” Palestinians, serves to accentuate the fact that the archive’s power is more in its ability to evoke the conflict that was to come when these portraits were made and the personal histories disrupted than in its ability to remove its subjects from a political context.

Sharing the Sharjah Art Museum venue with Photo Kegham, documentary filmmaker Mila Turajlić mobilises an archive to reinterpret our current reality. Based on the artist’s archival project accessing a trove of forgotten newsreels that document African and Asian liberation movements in the 1960s and 70s, Turajlić’s ongoing workshop series Voices from the Debris (2023–ongoing) invites participants in countries where the newsreels were filmed to discuss in live narration what the images on the silent reels evoke for them. Calling to mind the biennial’s abiding and exemplary commitment to art from the Global South, the recordings of these workshops give voice to those who are historically muted. With archival material featuring so heavily, the question remains whether, without creative activation, the archive alone constitutes a work with artistic value.

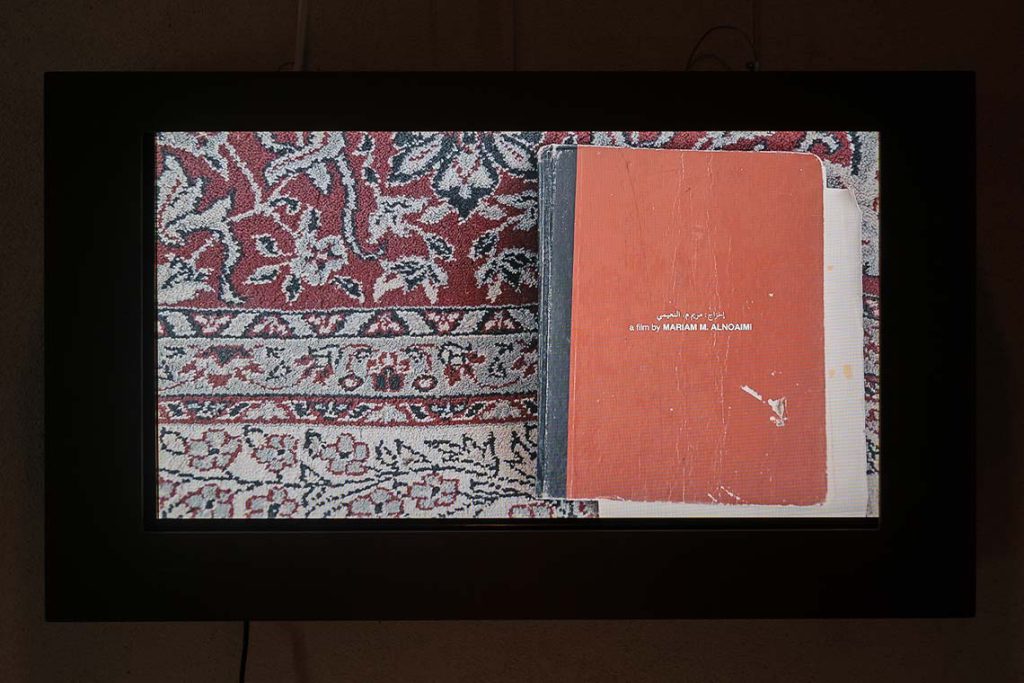

Everywhere in the exhibition are works worthy of considerable meditation, addressing loss and destruction, memory and history – and imagining alternate realities or exploring speculative futures. If many of them reflect on the perils of contemporary life, many more examine the conditions that have given rise to that precarity. A future in which a global disaster has erased all personal data is part of a new commission by Cécile B Evans. The films RECEPTION! (2024) and MEMORY! (2025) hold a warning of what could be in store for us, as a narrator scolds a protagonist in the midst of losing an individual memory: “You made a belief system you thought would keep you safe … you learned the closed loop of liberalism. Like an inheritance, you took it in.” In a system in which data grows more accepted as crucial to our personhood, how we carry our identities forward opens up to new vulnerabilities. An intimate filmed reading of the diary of artist Mariam M Alnoaimi’s grandfather, a fisherman in Bahrain, recites the notes he took to mark the location of sand formations and record species information. In The Water That Asked for a Fish–The Red Book(2025), Alnoami examines the relationship of the communities of the Gulf with the sea as one not only characterised by adjustment to decades of rapid transformation – a familiar narrative around Gulf countries – but also changed by ecological destruction wrought by humans. “I want to see and compare what would happen after all this time and what the change would be,” her grandfather says in the journal’s introduction. “That is why I write this book”.

Documentation of feminist artist exchange Womanifesto appears across several venues, alongside other works rooted in social movements, such as collaborations between artists and the support and campaigning charity, The Voice of Domestic Workers. These provide a welcome lifeline to the real world in the midst of so much abstraction. The work of pioneering performing artist Suzanne Lacy, also scattered throughout the show, includes a 1977 performance protesting sensationalised media narratives around the murders of 10 women by a serial killer, and a project in the 1980s examining how pop culture depicts aging women. The latter feels almost transgressive, not only as it addresses a topic still underdiscussed today but because it does so with the participation of 430 female senior citizens.

Confrontation as a positive relational method also shapes Lacy’s work,The Circle and the Square (2015–17). Basing a musical performance on her research into the impact of the declining textile industry on the South Asian and White residents of northwest England, Lacy invited practitioners of Shape Note singing, a tradition of social singing, to join a local Sufi group practicing Dhikr, an Islamic form of chanting. Five hundred local people gathered for the three-day singing event, and experiencing the large-scale video documentation is profoundly emotional. From venue to venue, outlines of thematic groupings begin to emerge, although it can be a challenge to discern where one of them (or even an individual work, in some instances) ends and another begins – likely a symptom of the five different visions and sets of priorities of the show’s curators: Natasha Ginwala, Amal Khalaf, Zeynep Öz, Alia Swastika and Megan Tamati-Quennell.

As Noémie Goudal’s Supra Strata(2024) unfolds, the camera pulls back to reveal the artist’s studio setup and then zooms back in on a diorama-like layering of jungle images, which she slowly melts by pouring a toxic liquid over them. In the familiar motif of industrial destruction of the natural environment, something interesting happens when these super-rich images combine with the strange sensory-psychological effects triggered by watching something dissolve to create an unsettling pleasure. Nearby, a gorgeous sci-fi film by Ayman Zedani mixes dread with a sense of relief, as the voice of giant ancient fungi – which may have been a source of petroleum deposits – tells the story of oil. In the return of the old ones (2020), the remains of the fungi address the humans who have used oil to build their world and now risk its very destruction. “Maybe this is what you and I were meant for, to bring about another change … all life is begotten to end … but will it be an act of nature or your doing?” the soothing male voice wonders, layered over scenes of an oil refinery and expanding cosmic plasma. In the end, the fungi suggest that what’s left of humanity will leave Earth and find its way back to the origins of all life, “to start all over again”.

Letting us off the hook for our treatment of the planet, and indeed of ourselves, the film provides relief in the context of an exhibition with so many stories about surviving, preserving and maintaining tethers “amidst tides of annihilation and tyranny”, write the curators. In a rare moment of visible conceptual framework in the exhibition, Zedani’s film at the near end of the Old Al Dhaid Clinic venue is in communication with Wael Shawky’sI Am Hymns of the New Temples(2023)at the other.The latter’s psychedelic rethinking of human origin myths puts puppets and masks to work, challenging how stories are formed and transmitted across the vastness of time and space and highlighting their function as markers as one civilisation dissolves into the next.

The Sharjah Biennial offers something of a challenge to Segun-Lean’s indictment of the biennial form as “fundamentally unable to bear the weight of its own contradictions”, although some of the works within comfortably resolve this by rendering the form (along with, well, almost everything) moot through notions of circularity and, as Alnoaimi’s grandfather says of the sealife, the fact that a day will come when it will no longer exist. Better then to take comfort from Cécile B Evans, whose narrator in MEMORY! asserts “It is what it is”.