The Petit Palais presents Paname, a layered and insightful show in which works by Algerian-born, Paris-based painter Bilal Hamdad thread throughout the museum’s permanent collections.

The solo exhibition Paname brings together twenty of Bilal Hamdad’s realist works, including two new oil paintings created specifically for this show, which was curated in-house by Annick Lemoine and Sixtine de Saint-Léger. Hamdad thrillingly thrusts contemporary Paris into this heritage space: locales of public transportation and terrasses – sites of ordinary moments in a lived day – take on the force of a patrimonial tableau. As such, the conversation between Hamdad’s works and the museum’s permanent collections is a fascinating one, highlighting evolutions in gender norms, disparities in racial representation and the way community and anomie both underpin metropolitan living. Showcasing cross-sections of the population that have not often – if at all – been rendered, his images have a regenerative effect on the collection by bringing them into a wider conversation about diversity.

In a five-minute introductory video at the entrance of the show, Hamdad states: “I use my camera as a sketchbook”. His process is to integrate varied photographic references into a single frame, yielding a wide ensemble of moving parts. Occasionally, he focuses on an individual. Hamdad’s long lengthwise painting Olivia (2025) showcases a young woman gazing upwards, as though surveying the gallery, a keen observer rather than one being observed. In her black dress and bright pink jellies, she is casual and independent relative to her neighbour, Portrait de Madame Edgard Stern painted in 1889 by Carolus Duran (who was a frequent conjurer of Parisiens and Parisiennes). Mme Stern’s opulence – jewellery, furs – stand in contrast to Olivia’s laid-back simplicity. Even nominally, they remain starkly different: Olivia is known by her own first name, whereas Madame is merely designated relative to her banker husband.

Image courtesy of the artist and TEMPLON, Paris – Bruxelles – New York

Across the way from Olivia, Garçon sur trottinette (2024) is, per the wall text, modelled after Édouard Manet’s L’enfant à l’épée (1861), which is not part of the collection. (Hamdad often visually quotes Old Masters, but subtly and freshly representative.) In situ, the young boy’s portrait is placed next to Fernand Pelez’s three-panel Grimaces and Misery: the Entertainers from 1888. The leftmost panel features a lineup of street children, limply fatigued or impatiently crossing their arms or glaring pointedly. The fragility of childhood feels heightened between Hamdad’s quiet boy paused alone in the frame and the relentless circus in which Pelez’s youth are forced to partake.

In the same gallery, two Hamdad paintings flank Leon Lhermitte’s Les Halles from 1895, a monumental work replete with food deliveries within the swarming, animated Parisian market. The triviality of the setting – as opposed to, say, posh parlours depicted in the same room – is intensified both by the boisterous throngs of market vendors and the gigantic proportion of the work. Hamdad’s nearby paintings share in that workaday urban hum: while Leon Lhermitte’s canvas is filled with heads of cabbage and live chickens and crates of pears, as well as the labour of sorting, distributing and selling, Hamdad equally loads his work with collective activity. On one side of the Lhermitte painting is Café des Anges (2022), in which the quotidian café takes on a ritualistic grandeur around bistro tables littered with pints of beer, ashtrays, cigarettes, the mixing of assorted patrons and hospitality workers, as well as passersby. A girl on her laptop, a nomadic flower vendor, a leashed dog, bottles of ketchup, branded sneakers – they all share a frame and contribute to a vision of work and leisured intermingling.

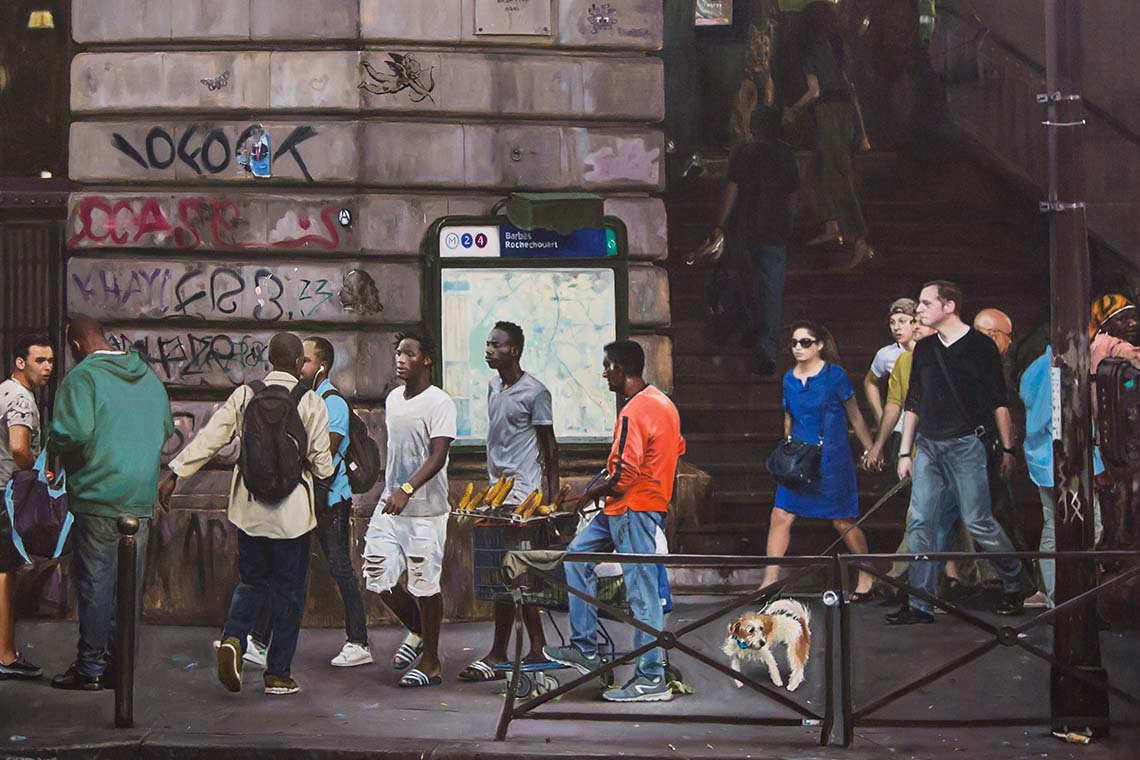

On other side of Lhermitte’s Les Halles is Rive droite (2021), which also feels like a synergistic glimpse at disparate lives, highlighting that miraculous urban alchemy whereby people cohabitate despite their differences. Rive droite is especially powerful because it specifically depicts Barbès Rochechouart, a metro stop to the north of Paris that functions as an entry point into a sector of the city with a significant African population. The people depicted at the mouth of the metro are heterogenous in age and race; there is graffiti on the wall, corn being grilled in a shopping cart and trash on the street. It is an area of the city that tourists and even other Parisians do not usually visit (in 2015 it was deemed part of the ‘no-go zones’ by the alarmist American media). To give Barbès Rochechouart pride of place is to celebrate its residents and neighbourhoods over the parts of Paris that are considered more illustrious. Nearby, Hamdad’s Paname (2025) further explores this neighbourhood in a way that feels almost orchestral in its arrangement – a mêlée of colors (pink dress, red plastic bag, yellow wax fabric), figures (child, musician, seller) and activities (mercantile and popular).

It is empowering to see mixed racial identities amidst the nearly all-white Eurocentric canon on display. Hamdad’s painting Angélus (2021), at the entrance of the exhibition, of a lone Black man in suspension perched on a handrail, stands in formal contrast to the sculptures nearby by Ernest Barriss (1898) and Pierre Jean David (1839) in paginated plaster casts. The sculptures’ bent knees and elbows akimbo have been given all the room to flaunt, while the silhouette of a Black man crouches tenuously, as though to symbolically underline his precarity in society at large. Across various other canvases, Hamdad excels at depicting figures in these transitive spaces – they feel liminal, and their irresolute state effectively unsettles the viewer.