Ishara Art Foundation’s group show, No Trespassing, brings the charged energies of street art into the white cube.

Making art in the street has historically been a way of claiming presence, a democratic assertion of identity in the public space. It often carries a political edge, offering counter-narratives to the polished, official language of city-makers. By its nature, it exists outside the traditional authority of institutions like galleries, curators and markets. It is curious, then, to consider what happens when this free and often-charged energy is translated into the pristine confines of the white cube. Ishara Art Foundation’s summer exhibition, No Trespassing, stages this encounter by inviting inside artists whose practices are rooted in public space to work in a space between the formal norms and hierarchies that usually define such settings. In doing so, it proposes the gallery not as a container for these works but as another kind of spatial encounter to experiment with ideas of ownership, agency and accessibility.

Perhaps the most confrontational staging, and the most conceptual, comes through with Rami Farook’s excavation of the gallery wall. Legible as an act of institutional irreverence against the white cube’s sanctity, or maybe a reframing of the gallery as a site with its own physicality – Gifts (2025) forms a literal rupture of the space. The Emirati artist reveals the wall’s structural framework, leaving some debris scattered on the floor. In this performative act of creation translated through erasure, he appropriates an urban vocabulary to speak within, or juxtapose, the institutional context with a sense of anti-formalism. This is further amplified as the work mirrors Dubai’s relentlessly evolving urban identity (notably, centrally planned) by resembling a construction site in flux. In this sense, it becomes an ironic reminder that the only space for such a disruptive intervention, an act that would be impossible on the city’s streets, is within the very institutional confines it seeks to critique.

Such paradoxes underpin the exhibition’s intent, as curator Priyanka Mehra weaves through a series of open-ended and contained contradictions. In a curatorial act of self-critique, the aesthetics of the street alongside the parameters of street art as both medium and genre, are invited into a formal space and remediated.

The World Out There (2025) by Fatspatrol (Fathima Mohiuddin) addresses these tensions with a direct continuation of her signature murals, painted across facades in Abu Dhabi and Canada. Here, she scales down her explorations and paints exuberant ink gestures directly onto the walls with a broom. This is paired with street-found objects — stop signs, cardboard, car number plates and planks of wood — turned into canvases bearing characters representing her inner world, in contrast to external realities. This duality, the Indian-born artist notes, reflects the ongoing struggle to find meaning and assert personal integrity amid challenges to individual autonomy.

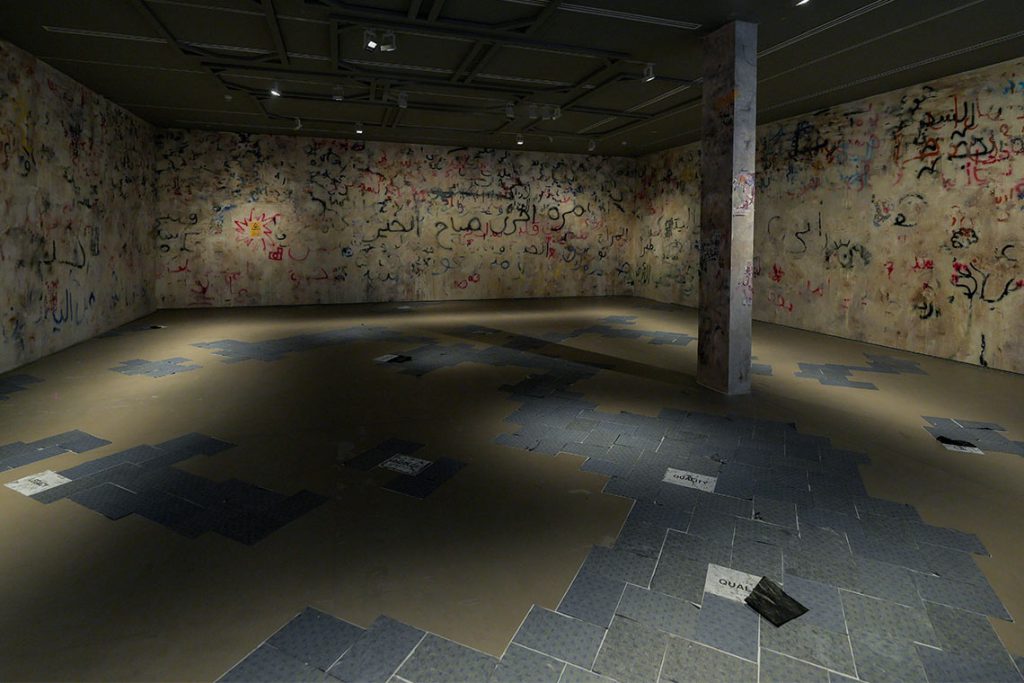

Palestinian artist Salma Dib also engages street art’s potential for personal expression with a focus on political activism. Her work sits at the rear of the exhibition in a grungy room, evocative of a dimly lit underpass, which feels like a fitting culmination of the show’s prior mounting frictions. Generational Wall: Orders and Echoes (2025) recontextualises the visual history of resistance and displacement from places like Palestine and Jordan, drawing on protest art and the ephemerality of refugee camps. She layers fading posters and fragmented spray-painted phrases to mirror the marks that accumulate across such politically and emotionally fraught surfaces. This density, appearing to have gradually obscured the intended messages over time, echoes how censorship and self-censorship operate in political discourse.

Underfoot, Khaled Esguerra’s Heritage Legacy Authentic (2025) invites the audience to gradually destroy this metaphorical spatial encounter. Each footstep scrapes away delicate layers of paper to reveal proclamations used to promote real estate developments across the UAE. Scrutinising such efforts to gentrify or commercialise traditional neighbourhoods, the artist questions how history and authenticity are curated at the expense of what already exists. He also urges us to consider whether these marketing promises truly benefit the environment and its inhabitants. Wedged between the vivid expressionism of Dib, Esguerra and Fatspatrol, Sarah Alahbabi’s For a Better Modern Something (2025) lends a more contained shift towards documentation, zooming out from street-level to an aerial perspective.

While each of the artists distinctly engages with urban space, a common thread is the creation of a counter-archive as a form of collective identity and personal memory that challenges the sanctioned histories of the city and the official ways in which it is represented. Alahbabi exemplifies this as she forms a threshold in the gallery and poses a cartographic assemblage, piling small concrete blocks imprinted with plans of neighbourhoods she has explored on foot, cut through with LED strips that denote the routes she takes. These vivid interventions form a live network that disregards the imposed order of streets to illuminate an intimate map of belonging and a record of a city that she has lived for herself.

our anthropocene conundrum (2025) by Nepalese street artist H11235 (Kiran Maharjan) continues the exploration of urban identity through two collages that blend photorealism and abstraction. The larger mural, layering found and locally source objects, distills architectural references from the streets of Dubai and Kathmandu, echoing the smaller, more representational collage ahead. Unable to travel to the UAE, H11235 collaborated with the Ishara team for the realisation, highlighting that, while street artists often claim space through direct mark-making, remote authorship can also carry significant weight.

Navigating these various stances and dualities, the curatorial structure of No Trespassing is both ambiguous and compellingly intentional. Particularly, its refusal to settle into a fixed interpretative mode is amplified by the absence of frames and descriptive wall texts, and by the replacement of a conventional introductory text with an abstract string of words, which shape a non-linear reading – much like the experience of wandering through a city. The works within oscillate between acts of urban intervention, archiving and the visual languages of the street, their resonances shifting and subverting the white cube’s traditional order in order to reposition how we look at art and the spaces that we inhabit or create within.